Dog disease could be boon for human medicine

- Published

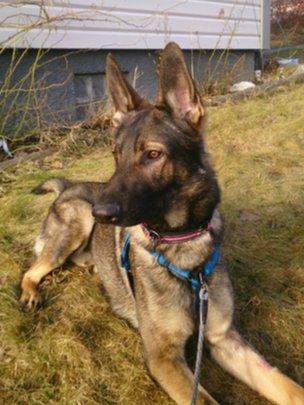

Texas has been diagnosed with OCD

Texas is a very energetic, smart and playful German shepherd dog. "He always tries his best to please me," said his owner Helene Bäckman.

But when Texas was six months old, Helene noticed that he started to behave unusually.

He started to jump and bite the air repeatedly.

"It´s like he sees something. He jumps and when he´s biting, he bites hard," she said.

"You can hear his teeth against each other.

"He can do this for hours and he gets more and more stressed when he´s doing it. He never rests between jumps."

The reason for Texas's unusual behaviour? Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

OCD is well described in humans and the dog version of the disease presents with similar repetitive behaviours.

Whereas people might wash their hands multiple times or hoard objects, dog symptoms include constantly chasing their own tails or shadows, blanket sucking or repeated grooming.

Texas's symptoms include a behaviour called fly-catching.

This is where dogs snap or chomp at the air as if they're trying to catch imaginary flies.

"It hasn't been easy to get him diagnosed because nearly all people around me have said that just the way he is," said Helene.

"I live in the north of Sweden and had to drive 700km to [the vet who diagnosed him] in Stockholm."

OCD is one of hundreds of diseases that the domestic dog suffers from that presents in a very similar way to the human form of the condition.

Other "human" conditions that dogs are susceptible include:

Epilepsy

Narcolepsy

Haemophilia

Cancer

Muscular dystrophy

Retinal degeneration

Although seeing our canine companions suffer may be upsetting, these shared diseases mean that dogs are emerging as one of the most important animal models of human hereditary diseases, advancing our understanding and paving the way for new therapies.

Genes for disease

Recent studies have identified genes that might cause the canine form of these conditions.

"It is much easier to find disease genes in dogs than in people," said Prof Kerstin Lindblad-Toh, of Uppsala University and the Broad Institute.

This is due to the fact that humans have been breeding dogs for hundreds of years.

Selecting dogs to create pups with specific characteristics has resulted in a certain amount of inbreeding, allowing disease-causing genes to become widespread in certain breeds.

This breeding history also means that all dogs within a breed are very similar genetically.

"This makes the search for the specific disease mutations less complex," said Prof Lindblad-Toh.

"In dogs we can find [disease-causing] genes with only a few hundred sick and healthy dogs, whereas in people thousands of patients and controls are needed."

In 2005, Prof Lindblad-Toh's team analysed all the genes of a female boxer called Tasha to produce an extremely accurate genetic sequence for the dog.

They, and other groups, have shown that the genetic sequence that makes up dogs like Tasha is quite similar to humans, meaning that many of the genes causing a disease in dogs may also be behind the manifestation of the condition in humans.

Prof Lindblad-Toh and her colleagues have recently published a study, external in Genome Biology which has identified four genes that are associated with OCD in dogs like Texas.

They are currently carrying out studies into whether these genes are also implicated in the human condition.

"Since the disease symptoms and medications used in dogs and people are similar, we expect that the same genes or other genes with similar functions will be responsible for the disease also in humans," said Prof Lindblad-Toh.

Pets are often used for these studies. The fact that they live in the same environment as us gives the dog another advantage over other disease models.

"Dogs are exposed to many of the same stressors that contribute to health problems," said Jon Bowen, behaviour consultant and veterinary surgeon at the Royal Veterinary College in the UK.

"Their diet often contains the leftovers from human meals, they are exposed to family stress (such as arguments and conflict), and are relatively socially isolated from members of their own species."

It is known that the environment can have an effect on how genes are expressed, and so any gene-environment interactions that cause human disease also affect our canine friends.

Dogs often suffer from conditions similar to those that affect humans

The role of rodents

Currently, researchers still rely heavily on genetically engineered mice to further our understanding of a whole range of conditions.

Whether ethically right or not, our knowledge of human disease has progressed considerably as our understanding of how we can genetically induce disease in mice has advanced.

But there are limitations. Research is done primarily in specific strains of young mice, specially bred for research and genetically manipulated to induce a disease.

You have to have some understanding of what genes you need to manipulate in order to induce the disease, and not every disease can be induced through such genetic manipulation.

"Naturally occurring diseases in animals are a lot more complex," said Holger Volk, professor of veterinary neurology and neurosurgery at the Royal Veterinary College.

"In a rodent you simplify a lot of things."

But these simplified diseases in rodents are far removed from the complicated reality of naturally occurring diseases.

Gorillas develop depression

"When you look at certain diseases in humans, there are so many factors which could be involved [in causing that disease]," Prof Volk said.

These factors, and the fact we are a complex organism, can often hinder our search for the underlying genetic cause of a disease.

The relative ease with which you can find disease-causing genes in dogs, combined with the shared organism complexity and environmental factors, means it is likely that understanding hereditary disease in dog will take us further in understanding human diseases that rodents can.

To human medicine

Using the dog for investigations into physical diseases has had already led to significant advances in our understanding.

For example, the identification of the genetic basis of narcolepsy in dogs led investigators to a previously unknown pathway in the brain, while other studies have led to the development of a new gene therapy for haemophilia, which is showing promise in clinical trials.

Experts say that there is increasing recognition of the value that veterinary medicine can bring to human medical studies.

"Wherever we can, we try to present our work at medical meetings and conferences, so that the medical profession can see what we are doing. Universally this gets a great response," said Mr Bowen.

There are also large schemes, such as the One Medicine Initiative, that hope to bring together researchers in medicine and veterinary medicine to solve health problems, currently being carried out that recognise the important link between the two fields.

"My research is driven to improve animal health," says Prof Volk. "And by doing that I can also help the human counterpart; it's a win-win situation for both species."