Antibiotic resistance now 'global threat', WHO warns

- Published

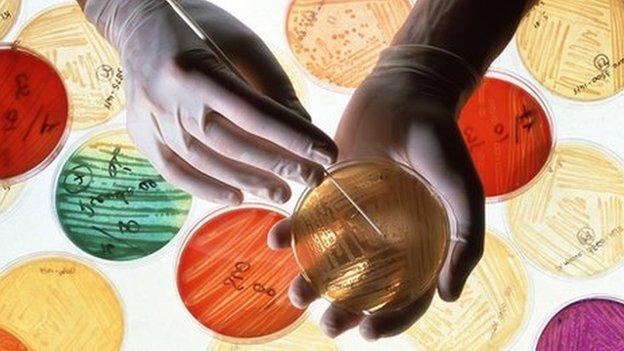

WHO called for more preventative measures against infection

Resistance to antibiotics poses a "major global threat" to public health, says a new report by the World Health Organization (WHO).

It analysed data from 114 countries and said resistance was happening now "in every region of the world".

It described a "post-antibiotic era", where people die from simple infections that have been treatable for decades.

There were likely to be "devastating" implications unless "significant" action was taken urgently, it added.

The report focused on seven different bacteria responsible for common serious diseases such as pneumonia, diarrhoea and blood infections.

It suggested two key antibiotics no longer work in more than half of people being treated in some countries.

One of them - carbapenem - is a so-called "last-resort" drug used to treat people with life-threatening infections such as pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and infections in newborns, caused by the bacteria K.pneumoniae.

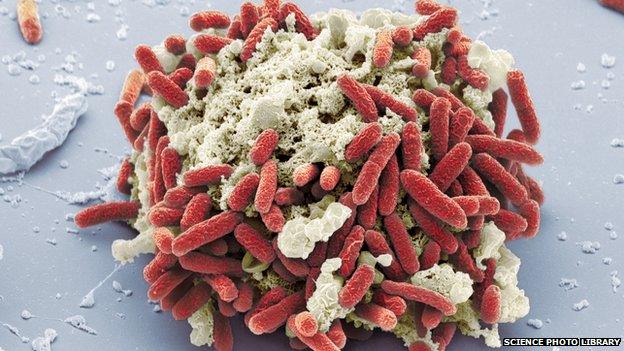

Bacteria naturally mutate to eventually become immune to antibiotics, but the misuse of these drugs - such as doctors over-prescribing them and patients failing to finish courses - means it is happening much faster than expected.

The WHO says more new antibiotics need to be developed, while governments and individuals should take steps to slow the process of growing resistance.

In its report, it said resistance to antibiotics for E.coli urinary tract infections had increased from "virtually zero" in the 1980s to being ineffective in more than half of cases today.

In some countries, it said, resistance to antibiotics used to treat the bacteria "would not work in more than half of people treated".

Gonorrhoea treatment 'failure'

Dr Keiji Fukuda, assistant director-general at WHO, said: "Without urgent, coordinated action by many stakeholders, the world is headed for a post-antibiotic era, in which common infections and minor injuries which have been treatable for decades can once again kill."

Urinary tract infections caused by E.coli bacteria are becoming harder to treat

He said effective antibiotics had been one of the "pillars" to help people live longer, healthier lives, and benefit from modern medicine.

"Unless we take significant actions to improve efforts to prevent infections and also change how we produce, prescribe and use antibiotics, the world will lose more and more of these global public health goods and the implications will be devastating," Dr Fukuda added.

The report also found last-resort treatment for gonorrhoea, a sexually-transmitted infection which can cause infertility, had "failed" in the UK.

It was the same in Austria, Australia, Canada, France, Japan, Norway, South Africa, Slovenia and Sweden, it said.

More than a million people are infected with gonorrhoea across the world every day, the organisation said.

'Wake-up call'

The report called for better hygiene, access to clean water, infection control in healthcare facilities, and vaccination to reduce the need for antibiotics.

Last year, the chief medical officer for England, Prof Dame Sally Davies, said the rise in drug-resistant infections was comparable to the threat of global warming.

Dr Jennifer Cohn, medical director of Medecins sans Frontiers' Access Campaign, said: "We see horrendous rates of antibiotic resistance wherever we look in our field operations, including children admitted to nutritional centres in Niger, and people in our surgical and trauma units in Syria.

"Ultimately, WHO's report should be a wake-up call to governments to introduce incentives for industry to develop new, affordable antibiotics that do not rely patents and high prices and are adapted to the needs of developing countries."

She added: "What we urgently need is a solid global plan of action which provides for the rational use of antibiotics so quality-assured antibiotics reach those who need them, but are not overused or priced beyond reach."

Professor Nigel Brown, president of the UK Society for General Microbiology, said it was vital microbiologists and other researchers worked together to develop new approaches to tackle antimicrobial resistance.

"These approaches will include new antibiotics, but should also include studies to develop new rapid-diagnostic devices, fundamental research to understand how microbes become resistant to drugs, and how human behaviour influences the spread of resistance."

- Published8 January 2014

- Published23 October 2013

- Published19 November 2015