Black Death skeletons give up secrets of life and death

- Published

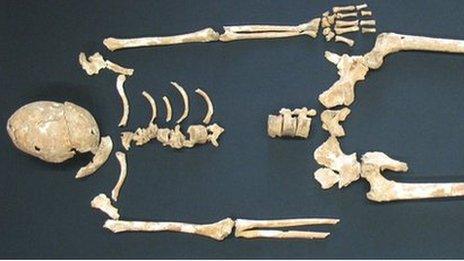

Museum of London Archaeology excavated the Royal Mint Black Death cemetery in the 80s

The medieval Black Death led to better health for future generations, according to an analysis of skeletons in London cemeteries.

Tens of millions of people died in the epidemic, but their descendants lived longer and had better health than ever before, a study shows.

The Black Death was one of the most devastating epidemics in human history.

But survivors benefited from rising standards of living and better diets in the aftermath of the disaster.

The improvements in health only occurred because of the death of huge numbers of people, said a US scientist.

It is evidence of how infectious disease has the power to shape patterns of health in populations, said Dr Sharon DeWitte of South Carolina University.

Lumps and black spots

The Black Death killed 30-to-50% of the European population in the 14th Century, causing terror as victims broke out in lumps and black spots, then died within days.

The elderly and the sick were most at risk of catching the bacterial infection, which was probably spread through sneezes and coughs, according to the latest theory.

The outbreak had a huge impact on society, leaving villages to face starvation, with no workers left to plough the fields or bring in the harvest.

However, despite analysis of historical records, little is known about the general health and death rates of the population, before and after the disease struck.

Dr DeWitte investigated how the deaths of frail people during the Black Death affected the population in London after the epidemic.

She analysed nearly 600 skeletons buried in London cemeteries to estimate age ranges, birth rates and causes of death for medieval Londoners living before and after the epidemic.

Samples dating several hundred years after the Black Death suggest survival and general health had improved dramatically by the 16th Century, with people living much longer than before the epidemic broke out.

The study, published in PLOS ONE, external journal, highlights the power of infectious diseases to shape patterns of health and population levels across history, said Dr DeWitte.

'Horrifying' aftermath

"It really does emphasise how dramatically the Black Death shaped the population," she told BBC News.

"The period I'm looking at after the Black Death, from about 200 hundred years after the epidemic. What I'm seeing in that time period is very clear positive changes in demography and health."

She said although general health might have been improving, the aftermath of the epidemic would have been "horrifying and devastating" for those who survived.

"Those improvements in health only occurred because of the death of huge numbers of people," Dr DeWitte said.

"This study suggests that even in the face of major threats to health, such as repeated plague outbreaks, several generations of people who lived after the Black Death were healthier in general than people who lived before the epidemic," she added.

The bacterium that caused the Black Death, Yersinia Pestis, has evolved and mutated, and is still killing today.

According to the World Health Organization, external, the modern day disease is spread to humans either by the bite of infected fleas or when handling infected rodents.

Recent outbreaks have shown that plague may reoccur in areas that have long remained silent.

- Published30 March 2014

- Published28 January 2014