Could bubonic plague strike again?

- Published

The Black Death killed millions of people in the 14th Century

Scientists have unlocked clues about the strains of bacterium causing two of the world's most devastating plagues, but could it ever kill on a mass scale as it once did?

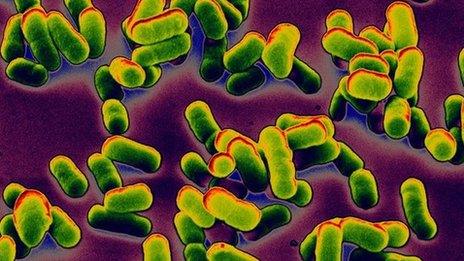

A team has compared the genomes of the Justinian Plague and the Black Death to find that both were caused by distinct strains of the bacterium Yersinia Pestis.

And while the Justinian Plague strain became extinct, the Black Death-causing pathogen evolved and mutated, still killing today.

Writing in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases, the research team said that knowing how the pathogen evolved in the past was crucial to help them understand possible future strains of plague.

In the 14th Century, the Black Death is thought to have killed up to half the European population - and 800 years earlier plague had caused similar devastation in the Byzantine empire when Justinian was emperor.

The team wondered why the earlier strain of plague died out while its cousin, the Black Death, was so successful, spreading worldwide and re-emerging in the 19th Century in Asia.

Plague family tree

To study it, scientists sequenced the Justinian Plague genome by looking at fragments of plague DNA from the teeth of two of its victims.

They then compared this ancient strain to known current strains of plague, to construct a plague "family tree".

The team conclude that the Justinian Plague was an "evolutionary dead end" but are not quite sure why.

DNA fragments were extracted from teeth

Lead author David Wagner from Northern Arizona University, US, said that it was not likely we would ever see a plague as deadly as the ones from history.

"Plague strains are always emerging from rodent reservoirs, causing disease in humans, but what we don't see are the widespread pandemics because now the public health response would be quick and very concentrated to shut that down."

He added that the strains today were just as deadly as the strains from the past but that "humans have changed".

"We have reduced rat populations and now have antibiotics that can be used to treat human outbreaks before they start to spread on a large scale."

Unlucky humans

But Hendrik Poinar of McMaster University, Canada, who also was part of research team, said that we should still be vigilant.

"The major implication is that this is a disease that can continue to emerge and cause nasty epidemics and so one should be constantly looking for the sourcing spots to where they came from."

He said that the evolution of Y.Pestis has clearly "boomed and gone bust" over time by generating novel mutations as rodents become immune to it.

Dr Poinar told the BBC that despite our modern medicine and better sanitation, frequent global travel could quickly help spread future strains.

The bacterium that caused the Black Death was first sequenced in 2011

Helen Donoghue is affiliated to University College London and was not involved with the study. She said it was impossible to know if the plague could ever re-emerge on a mass scale but argued that it was very unlikely.

"Humans are only accidental hosts for this organism, it's rodents and the animals that eat them (like fleas).

"It's only when the fleas are starving or when they run out of rats or other rodents - because of heavy rains or when the harvest fails - that fleas will go on to any alternative hosts. Humans were just unlucky."

And she added that at the moment there were so many rodents in the world that there would not be any selection pressures for fleas to look for other hosts.

Dr Poinar said questions remained about why the Black Death was so much more successful than the Justinian Plague, and that scientists would continue to study the problem.

And it is exactly by delving into the ancient DNA of these pathogens from the past, that researchers can begin to understand how they evolved, and why they were so deadly.

Bubonic plague threat - in 60 seconds

For more on this story, listen to Inside Science on BBC Radio 4 on Thursday 16:30 and 21:00. Listen to past episodes of the programme here or download the podcast here.

- Published10 October 2013

- Published13 June 2013

- Published12 October 2011