Eradicating polio one step at a time

- Published

Sita Devi says she is committed to keeping India polio-free

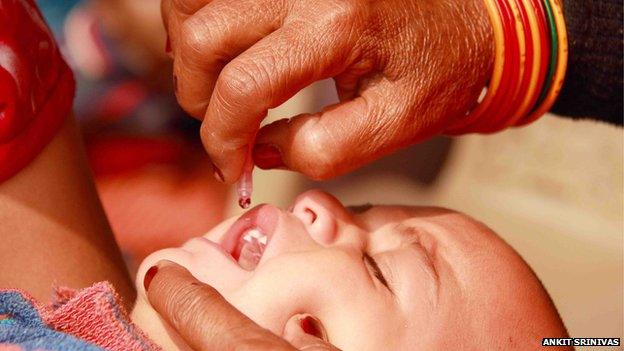

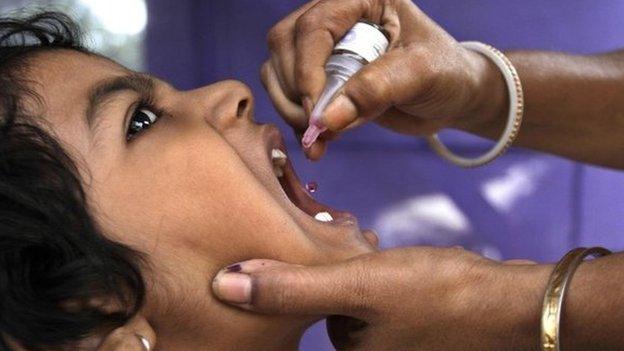

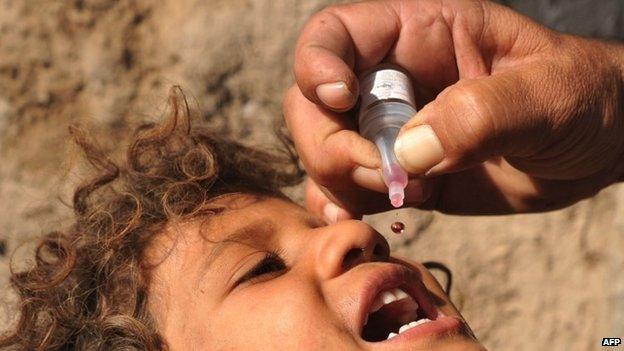

A few years ago, India accounted for half the world's cases of polio. Today it is officially clear of the disease. This remarkable feat is largely down to an army of women who, one step at a time, have crisscrossed the country on foot to give the under-fives polio vaccines.

Sita Devi is one of India's "polio aunties". The 57-year-old often walks miles in the searing heat to find children in remote villages and communities who need vaccinating.

She is one of the hundreds of thousands of women working in Aanganwadis - health care centres - in India which provide free basic services to those who cannot afford to pay.

They are part of the Pulse Polio Initiative that was started in 1995 with the aim of eradicating the disease from the country.

Sita Devi often walks long distances in the heat to reach families in need of the vaccine

Since then, 12.1 billion doses of polio vaccine, external have been administered here.

In 2006 India still accounted for half of all global cases of polio - but earlier this year it recorded three years without a new reported case.

This achievement allowed the World Health Organization (WHO) to finally declare its entire South East Asia region polio-free.

'New problem'

But now Ms Devi is worried. She doesn't know if she can persuade the families she works with in the rural areas around Allahabad in northern India to have their children immunised again.

She airs her concern at a morning meeting of Aanganwadi workers in one of Allahabad's regional health offices.

It's 45C (113F) outside and a rusty fan isn't doing much to cool the room down.

Ms Devi's worry is partly down to the success of the eradication programme - the next round of immunisations is due in June but many families do not see the logic in repeated vaccinations now that India is polio-free.

"This is a new problem. We must deal with it carefully so that people understand why we are giving the anti-polio drops," she tells Rajesh Singh, the regional health officer.

As a chorus of similar worries erupts, Mr Singh encourages the Aanganwadi workers to tell the families regular immunisation is important to keep the disease away.

Aanganwadi workers play a crucial role in India's fight against polio

He has to speak loudly to be heard among the debate and the creaking of the fan.

But his pep talk seems to work as the women enthusiastically prepare to leave for their respective areas.

'Committed to the cause'

"These women often cover more than 500 houses a day and they walk for miles. It's not money that drives them. These women work tirelessly because they feel committed to the cause," Mr Singh explains.

After the meeting Ms Devi steps out into the heat of the day and walks to the main road to find a public bus.

As we move slowly through the traffic towards a slum area, she says she mostly works in poorer areas to educate families about polio.

Money was never her motivation, she says.

Aanganwadi workers earn less than a pound on every visit to a field area, in addition to a monthly salary of just 4,000 rupees (£40).

But she has seen the impact of polio first-hand. She watched her own nephew grow up with the disease, unable to walk or manage basic activities.

"In 1998, I heard about the polio programme and asked the local health centre if they could treat my nephew. But they told me that the immunisation would only prevent the disease," she recalls.

India's Pulse Polio Initiative started in 1995 and in 2014 India recorded three years without a new polio case

It was a terrible disappointment that they couldn't help him, but it made her decide to join the fight against polio.

"I immediately signed up because I had seen how this disease destroys life. One family member always had to be with my nephew and we could never go out as a family.

"He has grown up now but still faces difficulty in moving around because India is not a disability-friendly country," she says.

'Polio aunty'

When we reach our destination, Ms Devi points out the lack of basic facilities like sanitation, electricity and even drinking water - typical of many Indian villages.

As she moves from house to house, I start to understand how the programme succeeded in the daunting task of eliminating the disease in a country of more than a billion people.

Her friendly nature helps villagers open up about their lives and problems.

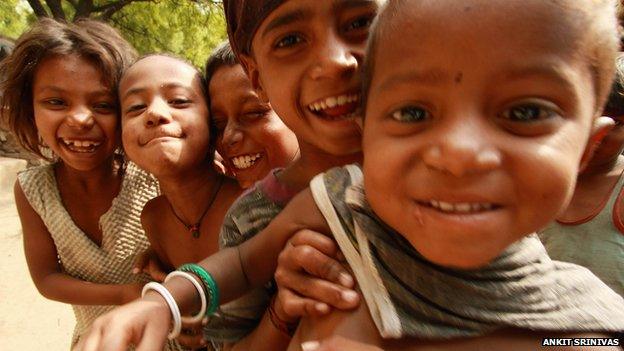

The children love their "polio aunty" who brings them sweets as well as anti-polio drops

"It is easier for people to trust me once they have shared some details about themselves with me.

"After speaking about their lives for a while, I can explain how they can protect their children against polio, which would be an additional burden to them," she explains.

As she walks through the slum, the children run barefoot after her, calling out to "polio aunty" for more sweets.

The high corruption levels in India make it difficult for people to trust government initiatives but Ms Devi insists that the polio programme is different.

One family is not keen on immunising its young ones, so she brings out the vaccination kit and explains how the drops are safe from contamination in the cool box.

She gives the children chocolates before she carries on.

Most polio workers carry large ice boxes to protect the vaccine

"I often get tired walking for eight to 10km [four to six miles] in the blistering heat to reach them.

"But I will continue to work as long as my health allows," says Ms Devi, smiling as she watches me wipe the sweat off my brow.

'We cannot afford to rest'

Her story is typical of many Aanganwadi workers who travel for miles to reach the areas they work in.

One of her colleagues, Ritu Tripathi, works 70 kilometres (41 miles) from home and stays away during the week.

She only sees her two young children on weekends, with her mother taking care of them in her absence.

"I cannot afford to travel by train very often and would rather invest my energy in the anti-polio campaign and other welfare programmes run by the government."

Poor wages are a real problem for the workers, and earlier this year there were Aanganwadi strikes in parts of India, external - but it was business as usual in her area.

"It would be nice if the government pays us more for our efforts, but even if they do not, I will continue to work," says Ms Tripathi.

By late afternoon I am exhausted from following Ms Devi as she works, and can barely imagine maintaining this routine every day for years.

But she is determined not to give up.

"We have fought hard to beat polio. But we cannot afford to rest if we want to remain free from the disease."

- Published13 January 2014

- Published26 March 2014

- Published11 February 2014

- Published1 March 2014