'Most dangerous day of their life'

- Published

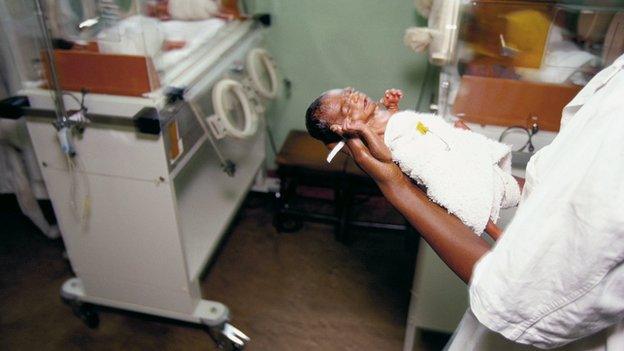

The day a premature baby is born is the most dangerous of its life. That's when the risk of death and disability is greatest. But doctors around the world are working to help more babies survive that day.

Of the 15m premature babies born every year around the world, one million will die.

Babies born too soon are vulnerable to infection and breathing can be difficult because of their underdeveloped lungs.

It's not always fully understood why babies are born early - but things which increase the likelihood include the age of the mother, some infections and if the woman has already had a premature baby.

Pre-term labour - defined as three weeks or more before the usual 40 weeks' gestation - is also higher in women from poor backgrounds, in multiple births (twins or more) or a condition called pre-eclampsia which causes high blood pressure and the only treatment is to deliver the baby.

Malaria can also cause a baby to be born early.

The 'survival gap'

In countries, including Congo, malaria can be a cause of premature birth

The first report on the global toll of prematurity was published just two years ago.

Born Too Soon, external estimated that low-cost interventions could prevent up to three quarters of premature baby deaths each year.

Modern medicine has helped, but the current limit of survival appears to be around 23 weeks - just over halfway through the length of a normal pregnancy.

There is a stark divide between rich and poor countries.

Two thirds of all premature births happen in just 15 countries, external.

Half of premature babies born at 24 weeks in developed countries survive, whereas half of babies born in developing countries at 32 weeks will die.

This has been dubbed the "survival gap".

Joy Lawn, professor of maternal, reproductive and child health and director of MARCH Centre, external at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine is a Ugandan-born paediatrician who has worked in countries like Ghana.

She says the stubbornly high number of deaths of premature babies is limiting success in trying to achieve the fourth Millennium Development Goal, external - to reduce the number of deaths of children under five by two thirds.

"We've seen a fantastic progress for reducing deaths for children under five but with much less attention to newborns, particularly preterm babies", says Prof Lawn.

"So now 44% of child deaths globally are in the first month."

Low cost measures

.jpg)

Professor Mimi Silveira, head of paediatrics, Goa Medical College, with an infant having ultraviolet light therapy to treat jaundice

India tops the list of countries where most premature babies are born - and 60% of deaths in under-fives are newborns.

But at Goa's Medical College in India, medics are working to reverse the trend by introducing basic measures aimed at preventing infections.

Dr Mimi Silveira insists all visitors to the neonatal intensive care unit wash their hands thoroughly and wear aprons and indoor shoes. The staff even sterilise the babies' clothes.

The measures appear to be helping.

Dr Silveira says: "Five years back our mortality rate was around 14% but last year it came down to 9.2% which I think is quite good.

"Also babies born at 28 weeks and below had a mortality rate of almost 90%. Last year we had come down to 50%."

One other low-cost method of improving the chances of premature babies is by giving their mothers corticosteroid injections, external - costing just 60 cents - to help mature the baby's lungs before it birth, which can halve the risk of the baby having breathing problems.

Overcrowding

Kangaroo care: a father bonds with one of his premature daughters in the neonatal unit of Goa Medical College

Families often feel bewildered by the shock of a premature birth and bonding can be more difficult than with a full-term baby.

Kangaroo care - where a baby is "worn" next to the mother's breast with direct skin-to-skin contact - helps to maintain a vulnerable baby's temperature, promotes breastfeeding and reduces the risk of infection.

Importantly it reduces the mortality rate, external in stable preterm babies.

The technique was pioneered by the Colombian doctor Edgar Rey Sanabria in the late 1970's - in response to overcrowding - there were too few incubators, so more than one baby had to be placed in each increasing the risk of infections spreading.

Kangaroo care is now proved to save lives - helping to enable babies to gain the strength to go home more quickly.

It also helps with bonding during those first few weeks when a hospital environment can feel strange and stressful to new parents.

'The loveliest feeling'

"I could hold Molly in the palm of my hand when she was born" Jo James

When Jo James gave birth to her daughter Molly at 28 weeks she weighed just under a kilo.

Jo had been pregnant with twins after four miscarriages. But during a 3D ultrasound scan at 24 weeks she was told that Molly's sister, Lily, had died.

She continued to carry both babies for a further four weeks.

"But then there was no movement at all, so I thought right, I am going up [to the hospital] to get looked at. I was in slow labour."

Both girls were delivered by Caesarean section.

.png)

Molly is now a happy, healthy 3 year old

"Lily was coming out first. If I'd gone into labour properly Lily would have come out and Molly followed - but she was too traumatised.

"When she was born she wasn't breathing. But the doctors were brilliant. I saw her little head but it was five minutes before she breathed."

Molly was "so small there were no clothes to fit her".

Jo was unable to hold her daughter for nine days - but then tried kangaroo care.

It was "the loveliest feeling", says Jo.

Molly, now three, only experiences minor effects after her birth says Jo.

"When she gets a cough she does get a bad chest infection. She's still on iron medicine to give her a bit of a boost, which she'll take until she's five at least."

Babies who are born very early - before 28 weeks - can often be left with lung problems, cerebral palsy and learning difficulties.

Even babies born just a few weeks early have higher rates of hospitalisation and illness than full-term infants. In addition to the human costs, preterm birth also costs $26 billion annually, according to the Institute of Medicine, external.

In the UK researchers have been following the progress of premature babies since 1995 in the EPICure study, external.

Many of the common difficulties like cerebral palsy - characterised by abnormal muscle tone like spasms - have begun to reduce according to Neil Marlow, professor of neonatal medicine at University College Hospital, London and one of the principal investigators of EPICure.

"We've seen that cerebral palsy has reduced quite dramatically over the last 10 to 15 years such that now we're beginning to see improvements for those babies who are most at risk which are those who are born very, very prematurely" , he says.

Monitoring

As well as intellectual impairment, another disability which can affect very premature babies is blindness.

Immature blood vessels at the back of the baby's eye can grow in a disorganised manner, resulting in scarring and detachment of the light-sensitive retina.

Oxygen therapy - given to babies born early who have problems breathing - increases the risk of this happening. So careful monitoring of babies is crucial, Prof Marlow says.

A baby's heart rate and breathing are monitored by a computer

"In terms of vision loss and retinopathy we've now been able to do trials which tell us exactly how much oxygen to give and how to monitor that oxygen.

"And we think this is going to lead to a reduction further, together with some new therapies that are coming along."

Now that doctors understand more about what helps to give a premature baby the best chance of survival the next challenge - to reduce the amount of disability in the children who do survive being born early - is one which parents like Jo James will follow with interest.

She now campaigns for the premature baby charity Bliss, external, along with the rest of her family.

Jo says: "Since I had Molly, all of my aunts and friends knit for me.

"And I take hampers to the Birmingham Women's Hospital where she was born every Christmas, along with a hat and cardigan for every baby, because I know how helpless it feels when all you want is for your baby to be all right."

Listen to The Truth About Life & Death: Prematurity on the BBC World Service