Breast cancer drug hope from leukaemia research

- Published

Leukaemia research may lead to new drugs for difficult-to-treat breast cancers, say scientists.

These types of tumours cannot be treated with the targeted drugs which have hugely improved survival.

A team in Glasgow says a faulty piece of DNA which causes leukaemia also has a role in some tumours and could help in research for new drugs.

Meanwhile, other researchers say they have taken tentative steps towards a blood test for breast cancer.

Oestrogen or progesterone positive breast cancers can be treated with hormone therapies such as Tamoxifen.

Another drug, Herceptin, works only on those tumours which are HER2-positive.

But around one in five breast cancers is "triple negative" meaning chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery are the only options.

Leukaemia

A team at the University of Glasgow investigated the role of the RUNX1 gene, which is one of the most commonly altered genes in leukaemia.

However, they have now shown it is also active in the most deadly of triple negative breast cancers.

Tests on 483 triple negative breast cancers showed patients testing positive for RUNX1 were four times more likely to die as a result of the cancer than those without it.

The results were published in the journal PLoS One.

One of the researchers, Dr Karen Blyth, said: "This opens up the exciting possibility of using it [RUNX1] as a new target for treatments."

She told the BBC: "First we need to prove this gene is causative to the cancer, if it is then what would happen if we did inhibit it?

"There's a couple of drugs in development in the US to target this gene from a leukaemia point of view, if they work we can test it in breast cancer cells."

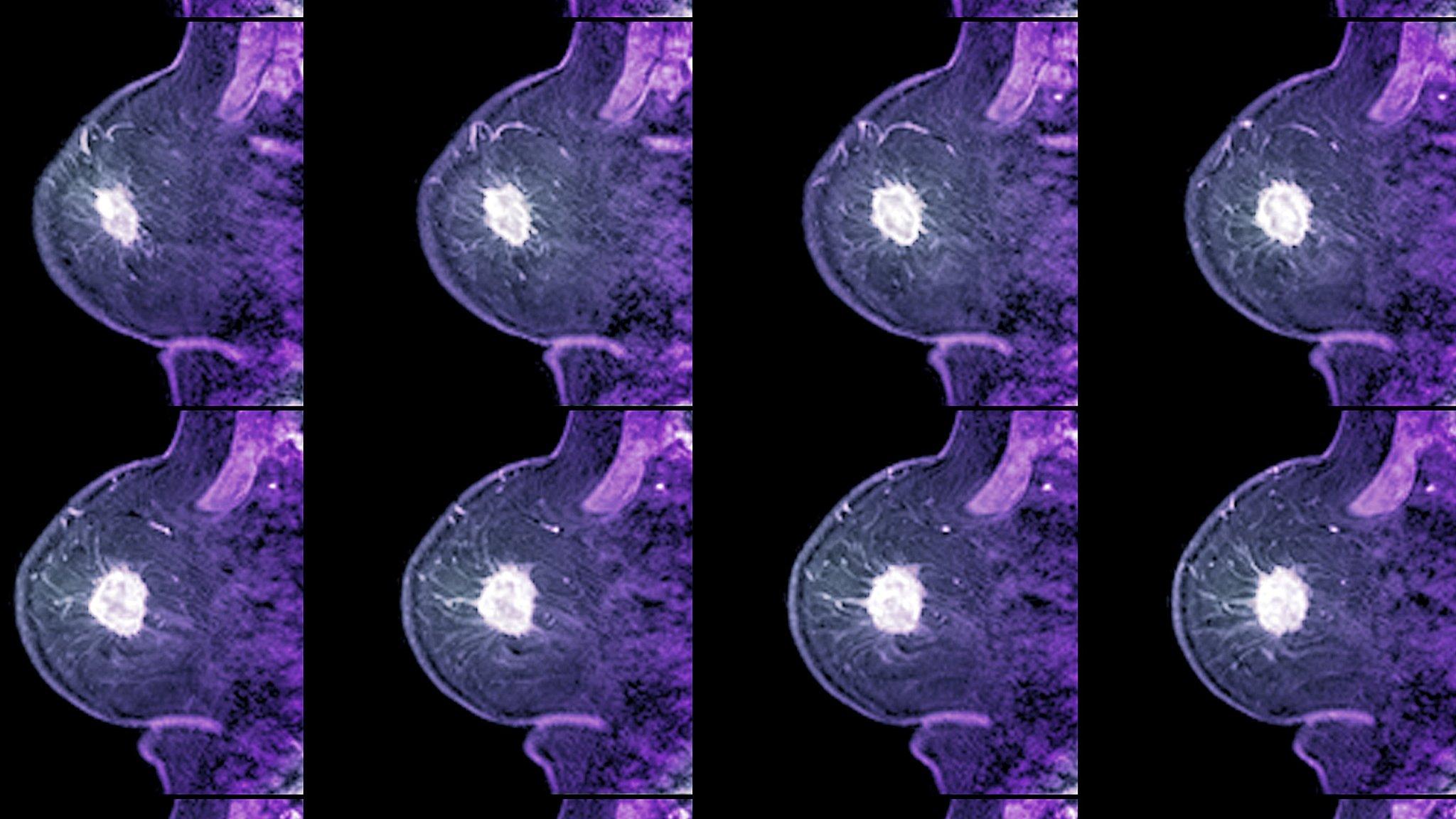

.jpg)

Could leukaemia lead to insight into breast cancer?

However, the gene has a complex role. Normally it is vital for cell survival and plays a critical role in producing blood. However, depending on circumstances, it can either encourage or suppress tumours.

It means any use of a drug to target the gene might cause side-effects.

Dr Kat Arney, the science communications manager at Cancer Research UK, said: "There's still so much we need to understand about triple negative breast cancers, as they can be harder to treat in some people.

"Almost two out of three women with breast cancer now survive their disease beyond 20 years.

"But more must be done and we urgently need more studies like these, particularly in lesser-understood forms of the disease, to build on the progress we've already made and save more lives."

Blood test

In a separate development, scientists at University College London think they have taken the first steps towards a blood test for breast cancer.

They found changes in the DNA of immune cells in the blood of women who were at high risk of breast cancer as they had inherited the BRCA1 risk gene.

Prof Martin Widschwendter, from UCL said: "Surprisingly, we found the same signature in large cohorts of women without the BRCA1 mutation and it was able to predict breast cancer risk several years before diagnosis."

They think it could become the basis of a blood test.

Dr Matthew Lam, senior research officer at Breakthrough Breast Cancer, said: "These results are definitely promising and we're excited to learn how further research could build on these findings."

- Published12 December 2013

- Published9 June 2014