Organ transplants: 'Supercooling' keeps organs fresh

- Published

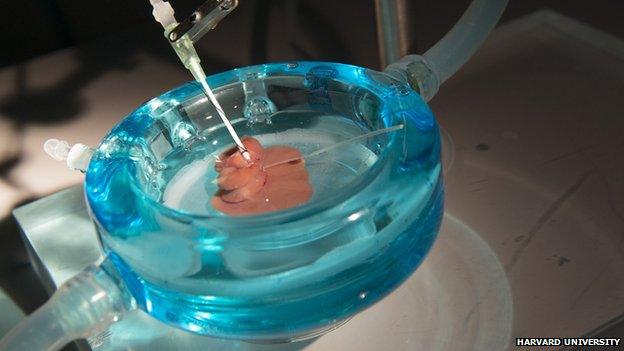

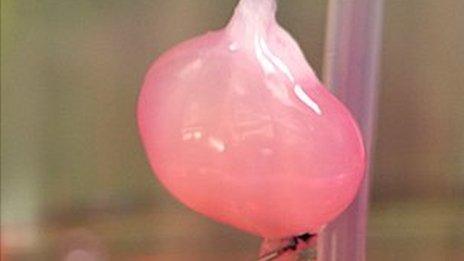

Scientists have tested the technique on rats' livers

A new technique can preserve organs for days before transplanting them, US researchers claim.

"Supercooling" combines chilling the organ and pumping nutrients and oxygen through its blood vessels.

Tests on animals, reported in the journal Nature Medicine, external, showed supercooled livers remained viable for three days, compared with less than 24 hours using current technology.

If it works on human organs, it has the potential to transform organ donation.

As soon as an organ is removed from the body, the individual cells it is made from begin to die.

Cooling helps slow the process as it reduces the metabolic rate of the cells.

Meanwhile, surgeons in the UK carried out the first "warm liver" transplant in March 2013 which used an organ kept at body temperature in a machine.

The technique being reported first hooks the organ up to a machine which perfuses the organ with nutrients.

It is then cooled to minus 6C.

Supercool

In experiments on rat livers, the organs could be preserved for three days.

One of the researchers, Dr Korkut Uygun, from the Harvard Medical School, told the BBC the technique could lead to donated organs being shared around the world.

"That would lead to better donor matching, which would reduce-long term organ rejection and complications, which is one of the major issues in organ transplant," he said.

He also argued that organs which are normally rejected, as they would not survive to the transplant table, might be suitable if they were preserved by supercooling.

"That could basically eliminate waiting for a organ, but that is hugely optimistic," Dr Uygun said.

Further experiments are now needed to see if the technology can be scaled up from preserving a 10g (0.35oz) rat liver to a 1.5kg (3.3lb) human liver.

The researchers believe the technology could work on other organs as well.

Dr Rosemarie Hunziker, from the US National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, said: "It is exciting to see such an achievement in small animals by recombining and optimising existing technology.

"The longer we are able to store donated organs, the better the chance the patient will find the best match possible, with both doctors and patients fully prepared for surgery.

"This is a critically important step in advancing the practice of organ storage for transplantation."

- Published15 March 2013

- Published15 April 2013

- Published21 October 2011

- Published18 March 2014