Ebola: Is bushmeat behind the outbreak?

- Published

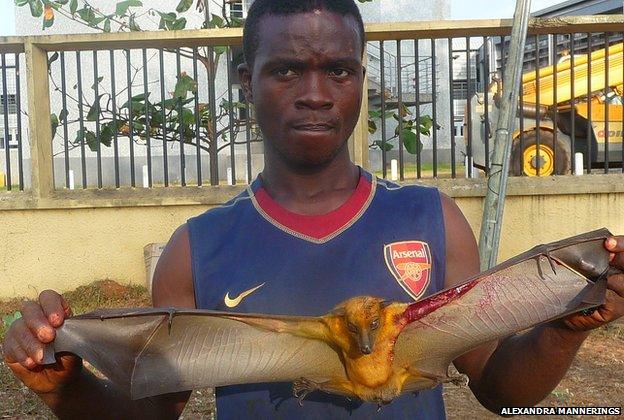

Bushmeat is believed to be the origin of the current Ebola outbreak. The first victim's family hunted bats, which carry the virus. Could the practice of eating bushmeat, which is popular across Africa, be responsible for the current crisis?

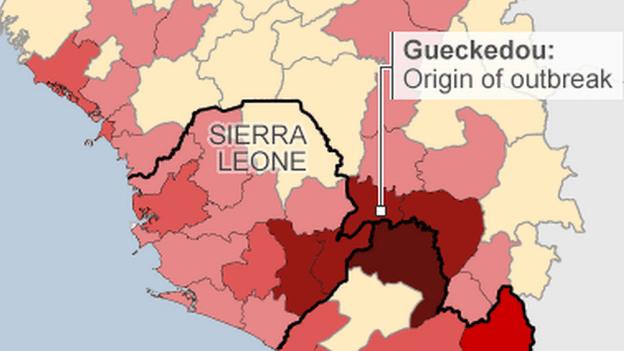

The origin has been traced, external to a two-year-old child from the village of Gueckedou in south-eastern Guinea, an area where batmeat is frequently hunted and eaten.

The infant, dubbed Child Zero, died on 6 December 2013. The child's family stated, external they had hunted two species of bat which carry the Ebola virus.

Bushmeat or wild animal meat covers any animal that is killed for consumption including antelopes, chimpanzees, fruit bats and rats. It can even include porcupines and snakes.

In some remote areas it is a necessary source of food - in others it has become a delicacy.

In Africa's Congo Basin, people eat an estimated five million tonnes of bushmeat per year, according to the Centre of International Forestry Research. , external

Ideal hosts

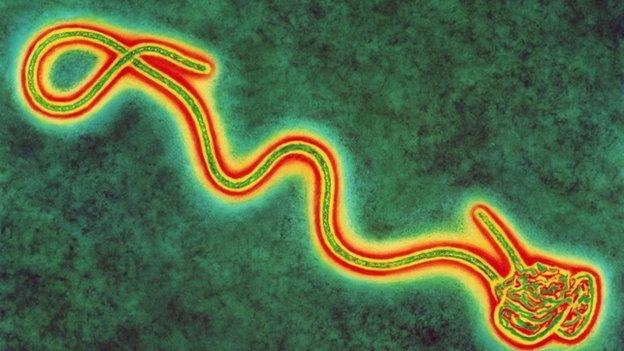

But some of these animals can harbour deadly diseases. Bats carry a whole range of viruses and studies have shown, external that some species of fruit bats can harbour Ebola.

Via their droppings or fruit they have touched, bats can then in turn infect other non-human primates such as gorillas and chimpanzees. For them, like us, this can be deadly. Bats on the other hand can escape from it unscathed. This makes them an ideal host for the virus.

Cooked or smoked bushmeat is not usually harmful

Exactly how the virus "spills over" into humans is still not clear, says Prof Jonathan Ball, a virologist at the University of Nottingham. There's often an intermediate species involved, like primates such as chimpanzees, but evidence shows people can get the virus directly from bats, he told BBC Inside Science.

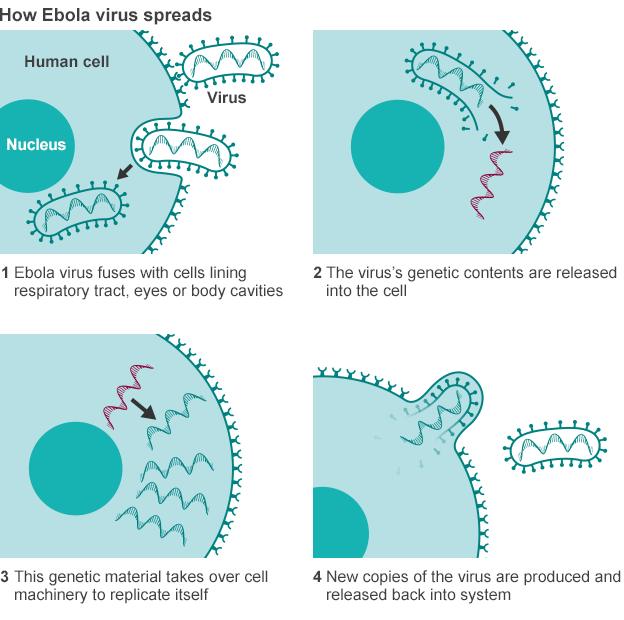

But it is difficult for the virus to jump the species barrier from animals into humans, he adds. The virus first has to "somehow gain access to the cells in which it can replicate" by contact with infected blood.

Most people buy bushmeat from markets once it has already been cooked, so it is those hunting or preparing the raw meat that are at highest risk.

The current outbreak shows that, however difficult or rare it is, infection is clearly possible - though it must be remembered that each further infection, from Child Zero to today, has been caused by contact with an infected person.

Bitten and scratched

There has been talk of banning bushmeat, but that may simply drive it underground, experts have previously warned, external.

Hunting bushmeat is also a longstanding tradition, explains Dr Marcus Rowcliffe from the Zoological Society of London,

"It's a meat-eating society - there's a feeling that if you do not have meat every day, you haven't properly eaten. Although you can get other forms of meat, there's traditionally very little livestock production. It's not so different from Europeans eating rabbits and deer."

Many West Africans eat bushmeat

It is sold in markets across the region

More than 100,000 bats are thought to be eaten in Ghana each year

In Ghana, for example, currently unaffected by the outbreak, fruit bats are widely hunted. To understand how people interact with this particular type of bushmeat, researchers surveyed nearly 600 Ghanaians, external about their practices relating to bats.

The study found that hunters used several different techniques to kill their prey including shooting, netting, scavenging and catapulting. All hunters reported handling live bats, which often meant they came into contact with blood and in some instances were bitten and scratched.

'Healthy food'

These hunters are therefore the most at risk of contracting viruses present in bats, explains one of the authors, Dr Olivier Restif from the University of Cambridge.

The work also uncovered that the scale of the bat bushmeat trade in Ghana was much higher than previously thought, with more than 100,000 bats killed and sold every year.

"People who eat bat bushmeat are rarely aware of any potential risk associated with consumption. They tend to see it as healthy food," he told the BBC's Health Check programme. This survey was carried out before the current outbreak but the team says that understanding the perceived risks could help control future epidemics.

Fruit bats are believed to be a major carrier of the Ebola virus but they do not show symptoms

While there is a risk, this study exemplifies that it is low. The estimate of more than 100,000 bats consumed has not resulted in a single case of Ebola in Ghana.

Researchers have also monitored populations of bats to test for Ebola and found very few animals with detectable levels of the virus. Since the first recorded outbreak in 1976 there have been only 30 single spillover events from animals into humans, according to new research, external which has mapped all previous outbreaks.

But given Ebola's animal origin, it is perhaps not surprising that bushmeat has been cited as a core danger associated with the outbreak.

An opinion piece in the New Scientist, external said: "The Ebola outbreak is an opportunity to clamp down on a practice which both causes disease outbreaks and empties forests of wildlife. At a minimum, governments should zealously enforce bans on the hunting and consumption of bats and apes."

Bushmeat is often smoked before eaten or sold at market

The Washington Post questioned, external "why West Africans keep hunting and eating bushmeat despite Ebola concerns".

Media coverage like this is not only unhelpful but dangerous, warns Prof Melissa Leach, an anthropologist at the University of Sussex.

"It's not a disease spread by eating bushmeat. As far as we know it originated in one spillover event from one bat to a child in Guinea.

"Subsequent to that it's been a human-to-human disease. People are more vulnerable to Ebola by interacting with people than by eating bats."

She says negative coverage of bushmeat "has deterred people from understanding the real risk of infection".

However, despite the current outbreak, the very fact that bats are carriers means there is always a risk of further infection.

Dr Rowcliffe says: "For any given contact the risk is quite low but given the scale of contact it is inevitable that there will be new emergences of Ebola or potentially other diseases that the bats harbour. The risks may be low but the consequences are severe as we are seeing at the moment."

This view is echoed by Dr Restif, who argues that because the world's population is expanding, close contract with wildlife will increase, which is often "the first driver of these events".

- Published14 January 2016

- Published8 October 2014

- Published22 September 2014