Why Ebola is so dangerous

- Published

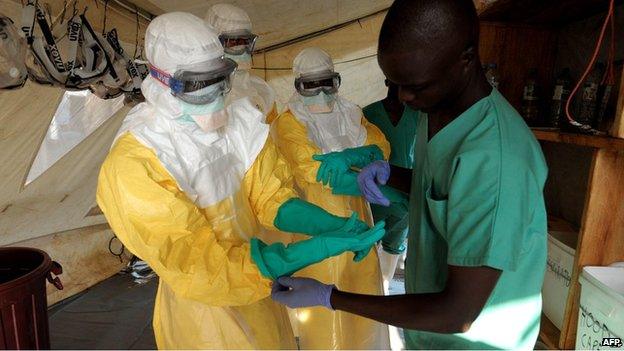

Healthcare workers are among those most at risk of catching Ebola

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa is the world's deadliest to date and the World Health Organization has declared an international health emergency as more than 3,850 people have died of the virus in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria this year.

What is Ebola?

Ebola is a viral illness of which the initial symptoms can include a sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain and a sore throat, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), external. And that is just the beginning: subsequent stages are vomiting, diarrhoea and - in some cases - both internal and external bleeding.

The current outbreak is the deadliest since Ebola was discovered in 1976

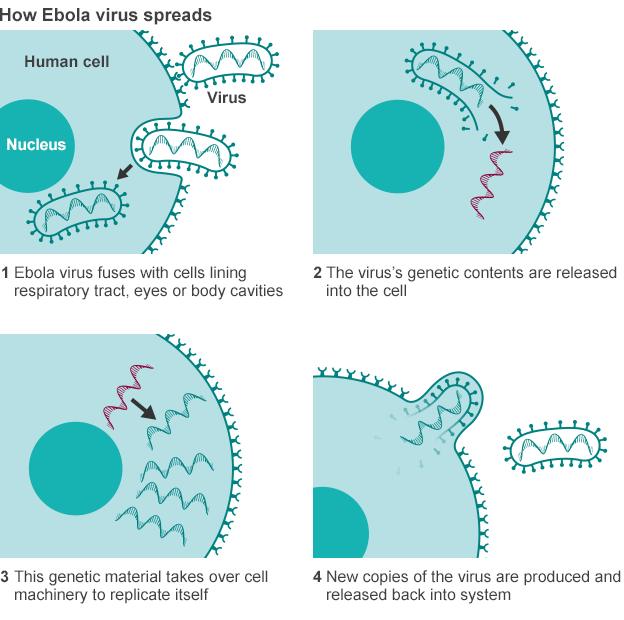

The disease infects humans through close contact with infected animals, including chimpanzees, fruit bats and forest antelope.

It then spreads between humans by direct contact with infected blood, bodily fluids or organs, or indirectly through contact with contaminated environments. Even funerals of Ebola victims can be a risk, if mourners have direct contact with the body of the deceased.

The incubation period can last from two days to three weeks, and diagnosis is difficult. The human disease has so far been mostly limited to Africa, although one strain has cropped up in the Philippines.

Healthcare workers are at risk if they treat patients without taking the right precautions to avoid infection. People are infectious as long as their blood and secretions contain the virus - in some cases, up to seven weeks after they recover.

Where does it strike?

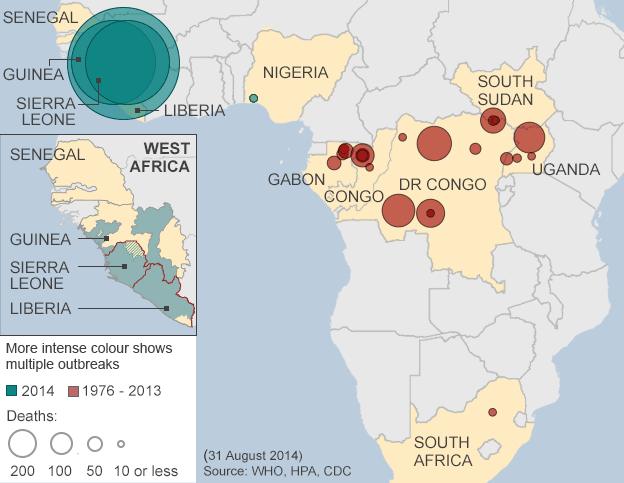

Ebola outbreaks occur primarily in remote villages in Central and West Africa, near tropical rainforests, says the WHO.

Bushmeat - from animals such as bats, antelopes, porcupines and monkeys - is a prized delicacy in much of West Africa but can also be a source of Ebola

It was first discovered in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1976 since when it has mostly affected countries further east, such as Uganda and Sudan.

Ebola deaths since 1976

This year's outbreak is unusual because it started in Guinea, which has never before been affected, and it quickly spread to urban areas.

Figures accurate from 4-6 October, depending on country. Death toll in Liberia includes probable, suspect and confirmed cases, while in Sierra Leone and Guinea only confirmed cases are shown

From Nzerekore, a remote area of south-eastern Guinea, the virus spread to the capital, Conakry, and neighbouring Liberia and Sierra Leone.

There have been 20 cases of Ebola being imported by someone travelling from a country of widespread transmission to Nigeria, with eight confirmed deaths. The US and Senegal have both confirmed one case each. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said in September that the virus might have been successfully contained in Nigeria and Senegal, external.

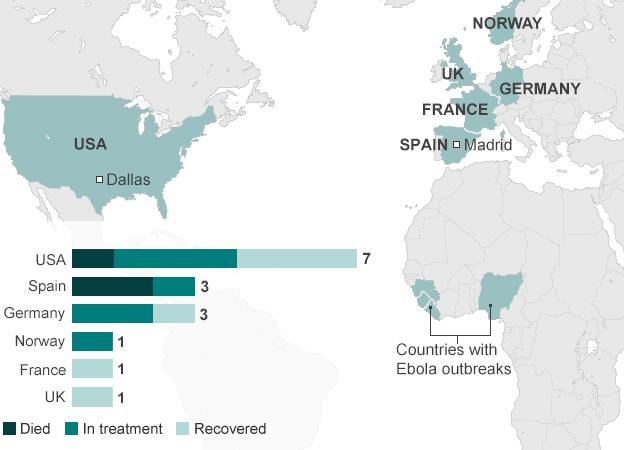

In October, a nurse in Spain became the first person to contract the deadly virus outside of West Africa, after treating two Spanish missionaries who had eventually died of Ebola in Madrid.

Ebola deaths

Figures up to 13 January 2016

11,315

Deaths - probable, confirmed and suspected

(Includes one in the US and six in Mali)

-

4,809 Liberia

-

3,955 Sierra Leone

-

2,536 Guinea

-

8 Nigeria

The medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) says the outbreak is "unprecedented", external in the way the cases were scattered in multiple locations across Guinea, hundreds of kilometres apart, and says it is a "race against time" to check people who come into contact with sick people, external in neighbouring Sierra Leone.

Can cultural practices spread Ebola?

Ebola is spread through close physical contact with infected people. This is a problem for many in the West African countries currently affected by the outbreak, as practices around religion and death involve close physical contact.

Hugging is a normal part of religious worship in Liberia and Sierra Leone, and across the region the ritual preparation of bodies for burial involves washing, touching and kissing. Those with the highest status in society are often charged with washing and preparing the body. For a woman this can include braiding the hair, and for a man shaving the head.

Strict precautions must be observed when burying those who have died of Ebola

If a person has died from Ebola, their body will have a very high viral load. Bleeding is a usual symptom of the disease prior to death. Those who handle the body and come into contact with the blood or other body fluids are at greatest risk of catching the disease.

MSF has been trying to make people aware of how their treatment of dead relatives might pose a risk to themselves. It is a very difficult message to get across.

All previous outbreaks were much smaller and occurred in places where Ebola was already known - in Uganda and the DR Congo for example. In those places the education message about avoiding contact has had years to enter the collective consciousness. In West Africa, there simply has not been the time for the necessary cultural shift.

What precautions should I take?

Avoid contact with Ebola patients and their bodily fluids, the WHO advises. Do not touch anything - such as shared towels - which could have become contaminated in a public place.

Washing hands and improving hygiene is one of the best ways to fight the virus

Carers should wear gloves and protective equipment, such as masks, and wash their hands regularly.

The WHO also warns against consuming raw bushmeat and any contact with infected bats or monkeys and apes. Fruit bats in particular are considered a delicacy in the area of Guinea where the outbreak started.

In March, Liberia's health minister advised people to stop having sex, in addition to existing advice not to shake hands or kiss. The WHO says men can still transmit the virus through their semen for up to seven weeks after recovering from Ebola.

-

Protective Ebola suit

× -

Surgical cap

×The cap forms part of a protective hood covering the head and neck. It offers medical workers an added layer of protection, ensuring that they cannot touch any part of their face whilst in the treatment centre.

-

Goggles

×Goggles, or eye visors, are used to provide cover to the eyes, protecting them from splashes. The goggles are sprayed with an anti-fogging solution before being worn. On October 21, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced stringent new guidelines for healthcare personnel who may be dealing with Ebola patients. In the new guidelines, health workers are advised to use a single use disposable full face shield as goggles may not provide complete skin coverage.

-

Medical mask

×Covers the mouth to protect from sprays of blood or body fluids from patients. When wearing a respirator, the medical worker must tear this outer mask to allow the respirator through.

-

Respirator

×A respirator is worn to protect the wearer from a patient's coughs. According to guidelines from the medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), the respirator should be put on second, right after donning the overalls.

-

Medical Scrubs

×A surgical scrub suit, durable hospital clothing that absorbs liquid and is easily cleaned, is worn as a baselayer underneath the overalls. It is normally tucked into rubber boots to ensure no skin is exposed.

-

Overalls

×The overalls are placed on top of the scrubs. These suits are similar to hazardous material (hazmat) suits worn in toxic environments. The team member supervising the process should check that the equipment is not damaged.

-

Double gloves

×A minimum two sets of gloves are required, covering the suit cuff. When putting on the gloves, care must be taken to ensure that no skin is exposed and that they are worn in such a way that any fluid on the sleeve will run off the suit and glove. Medical workers must change gloves between patients, performing thorough hand hygiene before donning a new pair. Heavy duty gloves are used whenever workers need to handle infectious waste.

-

Apron

×A waterproof apron is placed on top of the overalls as a final layer of protective clothing.

-

Boots

×Ebola health workers typically wear rubber boots, with the scrubs tucked into the footwear. If boots are unavailable, workers must wear closed, puncture and fluid-resistant shoes.

Fighting the fear and stigmatisation surrounding Ebola is one of the greatest challenges health workers face.

But health workers themselves are becoming scared of treating patients, and are demanding better protective clothing when exposed to patients.

Ebola has already claimed the lives of dozens of doctors and nurses in the Ebola-hit region, including Sierra Leone's only virologist and Ebola expert, Sheik Umar Khan.

This has put a further strain on the health services of these West African states, which have long faced a shortage of doctors and hospitals.

What can be done if I catch it?

You must keep yourself isolated and seek professional help. Patients have a better chance of survival if they receive early treatment.

The current outbreak is killing between 50% and 60% of people infected

There are no vaccines, though some are being tested, along with new drug therapies. The WHO ruled in August that untested drugs can be used to treat patients in light of the scale of the current outbreak.

The experimental drug ZMapp has been used to treat several people who contracted Ebola: Two US aid workers and a Briton have recovered after taking it but a Liberian doctor and a Spanish priest have died.

But the US pharmaceutical company that makes it says it has for now run out of it.

Patients with Ebola frequently become dehydrated so they should drink solutions containing electrolytes or receive intravenous fluids.

MSF says this outbreak comes from the deadliest and most aggressive strain of the virus.

The current outbreak is killing between 50% and 60% of people infected.

It is not known which factors allow some people to recover while most succumb.

Ebola: Experimental treatments

Ebola patients treated outside West Africa*

*In all cases but two, first in Madrid and later in Dallas, the patient was infected with Ebola while in West Africa.