Is there really a crisis among GPs?

- Published

GPs should have it all, shouldn't they?

A decade ago they got a new contract that allowed them to give up night and weekend cover, while seeing their pay shoot through the £100,000 a year barrier.

More recently, this government's reforms in England have put them at the heart of decision-making in the NHS by giving them responsibility for two thirds of the NHS budget.

And yet the profession, it seems, is at its wits end. A recent survey, external of 1,000 doctors by the British Medical Association found GPs had lower levels of morale and work-life balance than their medical colleagues elsewhere in the health service.

This negativity has started to filter through to young medics joining the profession. The government in England is in the process of expanding the number of training places, but at last count one in eight of the posts remained unfilled.

What has gone wrong? If you ask GPs, the answer is simple. They are being asked to do too much. The BMA survey found three quarters thought their workloads were "unsustainable".

There is plenty of evidence to back up these claims. A report, external produced by the Nuffield Trust think-tank - and given exclusively to the BBC - suggests that GPs have been caught between a rock and a hard place.

While numbers are rising slowly - up by 4% since 2006 to over 32,000 - this has been outstripped by rises in demand. According to estimates (unlike hospital visits their are no accurate figures) the number of patient consultations has risen by 13% to 340m in the last four years alone.

What is more, funding has been squeezed. In the past year spending fell by 3.8% in real terms to £7.55bn.

And this is not just an English phenomenon. Similar complaints are being made elsewhere in the UK. Just this week the Royal College of GPs was warning the GP system in Scotland was under-funded.

Dr Richard Vautrey, of the British Medical Association, says these factors are the "fundamental part of the problem".

"GPs are being asked to do more and more for less. The government is now talking about seven-day services, but at the moment doctors are struggling to provide good quality care during core hours. Without better funding the fear is patients will suffer."

Case study: The GP who gave it all up

Dr Mark Sandford-Wood had been a partner in practice in north Devon for 20 years when he decided enough was enough last year.

He now works as a "freelancer" doing locum shifts, out-of-hours work, providing care in prisons and sitting on local committees.

"I still love being a GP, but the financial risk was just too much. Funding is being squeezed and demands are going up. We have to do more and more paper work to chase little slithers of money. My take-home pay started falling and I began to question what the future held.

"It's not a matter of not wanting to work hard - I'm now working longer hours - but its a question of financial security. GP partners are running businesses and the numbers just don't tack up."

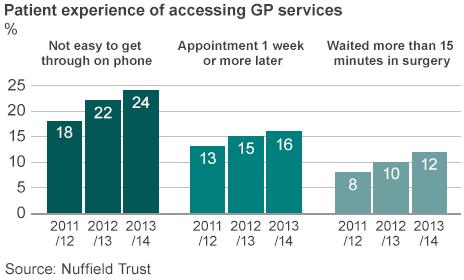

There are signs this is already beginning to happen. Data from the official GP patient survey, carried out by Ipsos Mori for NHS England, shows that patients are waiting longer for appointments and finding if more difficult to get through on the phone than two years ago.

The Royal College of GPs has called this worsening a "national disgrace" - and wants to see the workforce expanded by 8,000.

But is there more to the problem that just simple money? Perhaps. What is noticeable about the Nuffield Trust review is how radically the sector has changed.

At one time, general practice was dominated by small practices where the GPs all had a stake in the surgery. It is why the profession has been called a network of small businesses.

But that is no longer true. A fifth of GPs are now salaried - effectively employees of the business - while the organisations they are working for are getting bigger and bigger.

'Tough job'

The number of single doctor practices has almost halved between 2006 and 2013 to under 900. Meanwhile the number of practices with 10 or more GPs has increased by three quarters to 510 in 2013 over the same period.

Talk to GPs and they will tell you that this is a consequences of the extra services they are being asked to take on and the extra management responsibilities they have been asked to take on.

Just last month the five-year plan set out by NHS England called on them to extend into other areas of care - such as minor surgery, diagnostics and specialist clinics - that have traditionally been the remit of hospitals.

Nuffield Trust chief executive Nigel Edwards has some sympathy for the profession. "Being a GP is a tough job. You can be faced with a patient who has a cold or lung cancer - the opportunity to get things wrong actually is quite high.

"As time has gone by, we keep asking more and more of them and if they are going to be able to cope things are going to have change."

Mr Edwards cites technology as a key area that needs embracing, pointing out that many GP practices are still communicating with fax machines to make his point.

He believes much more could be done on the telephone or by using modern digital technologies and a continued move towards larger practices or - at the very least - practices working together in networks so they benefit from economies of scale.

But as this shift towards bigger, better, faster happens is there a danger that the special relationship GPs have with their patients is lost?

Not necessarily, says Mr Edwards. "If the profession does embrace change, GPs may actually find some of the pressure is eased and that continuity of care becomes easier. Some in the profession realise that, but some don't." The conclusion could not be starker: innovate to survive.