Why are hospitals under so much pressure?

- Published

You need look no further than Salford Royal Hospital to realise the point the NHS has got to.

The trust is generally regarded as one of the best - if not the best - in the UK. It outperforms its counterparts on a whole host of measures from patient satisfaction to waiting times.

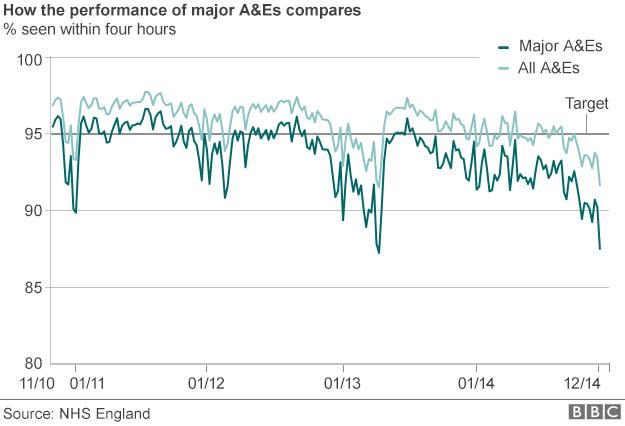

But in early December it missed the four-hour A&E waiting time target - dipping below the 95% standard by the narrowest of margins. Since then weekly performance has got even worse. This is not a quirk. It's been dragged down along with the rest of the hospital sector.

Once you strip out the small units and walk-in centres, where the pressure is less intense, nearly all England's major units are now missing the target.

This is why the NHS in England has just posted it worst performance in a decade.

Performance levels in Wales and Northern Ireland are even lower (Scotland seems to be performing at a similar level to England, although as the data there lags behind the other parts of the UK, it is hard to say for sure).

This is despite ministers in all four corners of the UK handing the health service extra money to deal with winter pressures.

So why are things deteriorating? The quick answer - and the one that was pointed out repeatedly in the past few weeks - is that attendances are going up across the UK.

As England has the best and most up-to-date figures, external, let's have a look at these. During the first week of December there were just over 436,000 visits - up by nearly 30,000.

Get involved on:

But what is interesting as you delve down into the data is that it's not just A&E units that are finding it difficult - there are pressure points across the whole system.

Nearly a fifth of patients who go to A&E need to be admitted into the hospital for more complex care than can be given in an emergency department.

Sometimes they face long waits (classed as over four hours) before a bed can be found for them. These are known as "trolley waits". The current levels being seen are the worst since records began in 2010.

But hospitals are also finding it difficult to discharge patients. The figures for October and November, external, the last full month for which they are available, were at their highest since that data set began in 2010.

A significant factor in this is the squeeze on councils' social care budgets. Many of the patients who end up in hospital are frail and elderly, and when they are ready to be released need support in the community to get back on their feet. If it's not there, they have to stay in hospital, which occupies a bed often needed for other patients.

Another pressure point is at the other end of the system - before the visit to hospital is made. Both the Royal College of GPs and British Medical Association have been vocal about the workload their members are facing.

A recent BMA survey, external found three quarters of doctors said their caseload was "unsustainable" - and that seems to have started impacting on patients, as latest data from the official NHS England patient survey shows they are finding it more difficult to get an appointment.

If GPs are unable to keep pace with demand, the obvious place patients turn to is A&E.

To be fair to ministers across the UK, they have recognised this. Wales, Scotland and England have all published plans in the last 18 months to relieve the pressure on the urgent and emergency care systems.

But these are all long-term solutions. In the short-term, all eyes are on what happens this winter.

So what next? "Predictions are very hard to make," says Chris Hopson, of NHS Providers, which represents hospitals. "What we don't know is what will happen with Norovirus or flu. Services are so stretched at the moment, that all it will take is a spike in those to make it very difficult for us."

It seems to be the case that despite all the planning, all the money, and all the hard work of NHS staff, this winter will hinge on factors outside everyone's control.