Hibernating hints at dementia therapy

- Published

Neurodegenerative diseases have been halted by harnessing the regenerative power of hibernation, scientists say.

Bears, hedgehogs and mice destroy brain connections as they enter hibernation, and repair them as they wake up.

A UK team discovered "cold-shock chemicals" that trigger the process. They used these to prevent brain cells dying in animals, and say that restoring lost memories may eventually be possible.

Experts have described the findings as "promising" and "exciting".

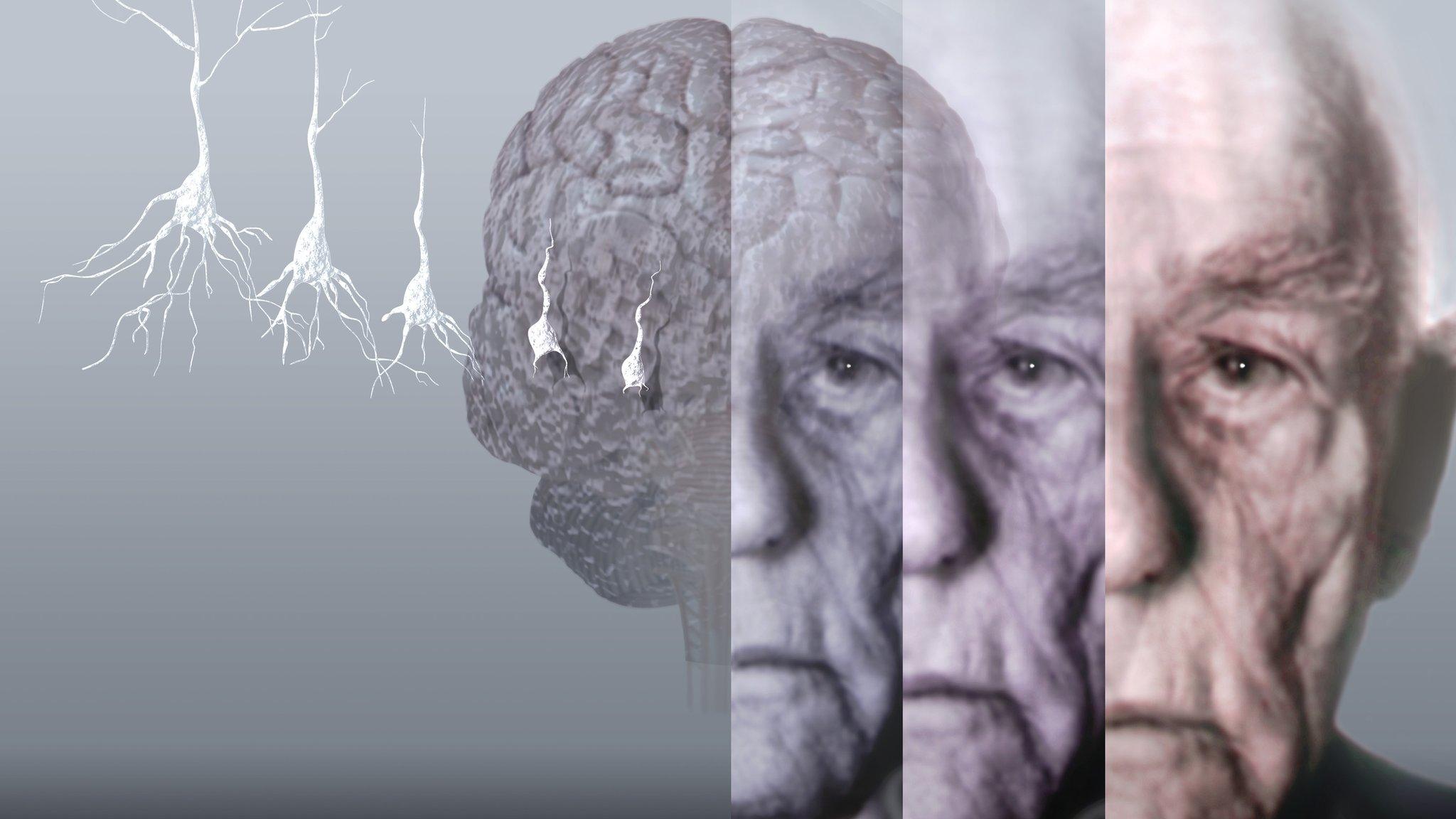

In the early stages of Alzheimer's, and other neurodegenerative disorders, synapses are lost. This inevitably progresses to whole brain cells dying.

But during hibernation, 20-30% of the connections in the brain - synapses - are culled as the body preserves precious resources over winter.

And remarkably those connections are reformed in the spring, with no loss of memory.

Hibernation lessons

In experiments, non-hibernating mice with Alzheimer's disease and prion disease were cooled so their body temperature dropped from 37C to 16-18C.

Young diseased mice lost synapses during the chill and regained them as they warmed up.

Old mice also lost brain connections, but were unable to re-establish them.

The study, published in the journal Nature, external, found levels of a "cold-shock" chemical called RBM3 soared when young mice were chilled, but not in old mice.

It suggested RBM3 was key to the formation of new connections.

In a further set of tests, the team showed the brain cell deaths from prion disease and Alzheimer's could be prevented by artificially boosting RBM3 levels.

Prof Giovanna Mallucci, from the MRC Toxicology Unit in Leicester, told the BBC News website: "This gives us a target to develop a drug in the same way paracetamol is used for a fever rather than a cold bath."

Memory back

Memories can be restored during hibernation as only the receiving end of the synapse shuts down.

I asked Prof Mallucci if memories could be restored in people if their synapses could be restored: "Absolutely, because a lot of memory decline is correlated with synapse loss, which is the early stage of dementia, so you might get back some of the synapse you've lost."

The discovery comes from the laboratory that was the first to prevent the death of brain tissue in a neurodegenerative disease.

It is still only an interesting concept, but has attracted some praise.

Dr Doug Brown, the director of research and development at the Alzheimer's Society said: "We know that cooling body temperate can protect the brain from some forms of damage and it's interesting to see this protective mechanism now also being studied in neurodegenerative disease.

"Connections between brain cells - called synapses - are lost early on in several neurodegenerative conditions, and this exciting study has shown for the first time that switching on a cold-shock protein called RBM3 can prevent these losses.

"While we don't think body cooling is a feasible treatment for long-term, progressive conditions like Alzheimer's disease, this research opens up the possibility of finding drugs that can have the same effect. We are very much looking forward to seeing this research taken forward to the next stage."

Dr Eric Karran, the director of research at Alzheimer's Research UK, said the study was "promising" and "highlights a natural process nerve cells use to protect themselves".

He added that "a future treatment able to bolster nerve cells against damage could have wide-reaching benefits".

- Published10 October 2013

- Published8 July 2014

- Published9 March 2014

- Published10 October 2013