Drugs in dirt: Scientists appeal for help

- Published

Samples have already been taken from a lake near the Seward mountains in Alaska

US scientists are asking the public to join them in their quest to mine the Earth's soil for compounds that could be turned into vital new drugs.

Spurred on by the recent discovery of a potential new antibiotic in soil, the Rockefeller University team want to check dirt from every country in the world.

They have already begun analysing samples from beaches, forests and deserts across five continents.

But they need help getting samples.

Which is where we all come in.

Citizen science

On their Drugs From Dirt, external website, they say: "The world is a big place and we can't get get to all of the various corners of it.

"We would like some assistance in sampling soil from around the world. If this sounds interesting to you - sign up."

They want to hear from people from all countries and are particularly keen to receive samples from unique, unexplored environments such as caves, islands, and hot springs.

Such places, they say, could house the holy grail - compounds produced by soil bacteria that are entirely new to science.

Researcher Dr Sean Brady told the BBC: "We are not after hundreds of thousands of samples. What we really want is a couple of thousand from some really unique places that could contain some really interesting stuff. So it's not really your garden soil we are after, although that will have plenty of bacteria in it too."

He said they would also be interested to hear from schools and colleges that might want to get involved in the project.

From the 185 samples they have tested so far there are some promising results, the researchers say in the journal eLife, external.

Biosynthetic dark matter

Dr Brady and colleagues have found compounds that might yield better derivatives of existing drugs.

In a hot spring sample from New Mexico, they found compounds similar to those that produce epoxamicin - a natural molecule used as the starting point for a number of cancer drugs.

In samples from Brazil, they found genes that might offer up new versions of another important cancer drug called bleomycin.

And in soils from the American southwest, they hope to find compounds similar to the drug rifamycin that could help with treatment-resistant tuberculosis.

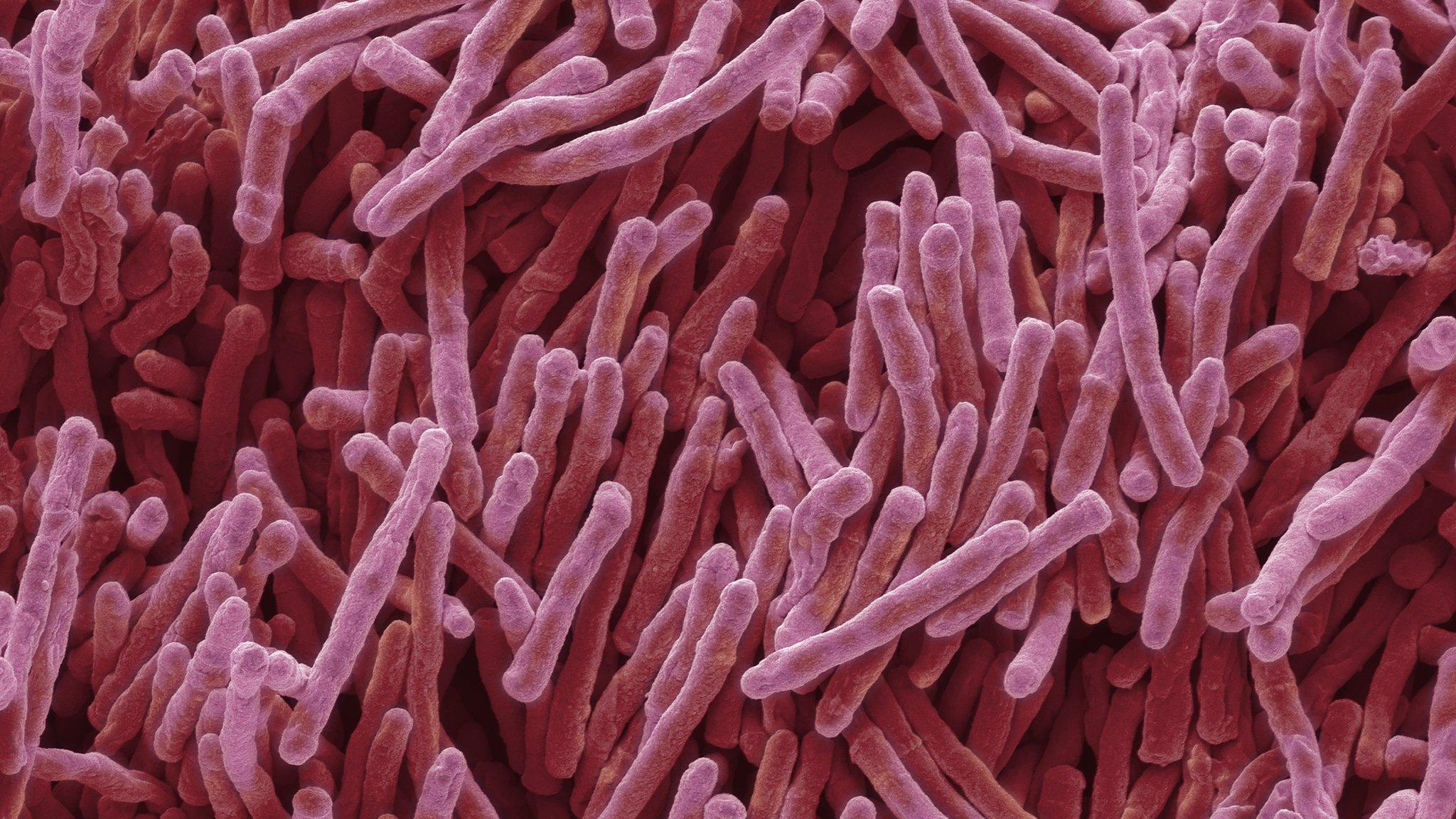

The soil bacterium Streptomyces lividans is a natural producer of the antibiotic Streptomycin

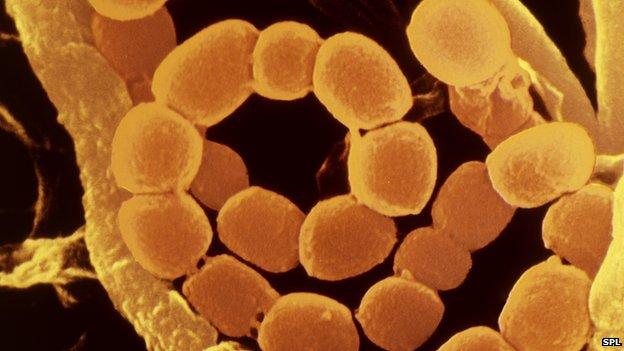

Many of the drugs we use today came out of dirt - the antibiotics penicillin and vancomycin to name just two.

Uncultured bacteria from the environment could provide a dazzling array of new molecules, many of which could become new medicines, say the research team.

There are more microbes in a teaspoon of soil than there are humans on earth, and only a tiny fraction have been cultured, they say.

Dr Brady, head of the Laboratory of Genetically Encoded Small Molecules, said: "We hope that efforts to map nature's microbial and chemical diversity will result in the discovery of both completely new medicines and better versions of existing medicines."

The scientists are beginning to identify hotspots around the globe where diverse soil bacteria can be found.

"The unbelievable diversity we found is a first step towards our dream of building a world map of chemicals produced by microbes - similar to Google Earth's and others' maps of the world's geography," says Dr Brady.

Other scientists have been mining the sea bed for undiscovered drug candidate molecules.

Prof Marcel Jaspars from Aberdeen University has analysed over 1,500 bacterial strains from the bottom of the ocean, some millions of years old, and says 15 strains look promising.

"It's beginning to get quite interesting. We will soon go the Atacama Trench off the coast of Chile to look there. It's a unique environment. It's about 8,000m deep and really high in organic matter."

- Published2 July 2014

- Published7 January 2015