Ebola outbreak: Virus mutating, scientists warn

- Published

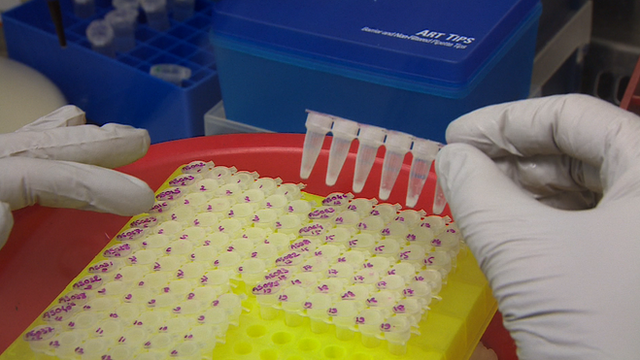

Hundreds of blood samples are being analysed to keep track of the virus

Scientists tracking the Ebola outbreak in Guinea say the virus has mutated.

Researchers at the Institut Pasteur in France, which first identified the outbreak last March, are investigating whether it could have become more contagious.

More than 22,000 people have been infected with Ebola and 8,795 have died in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Scientists are starting to analyse hundreds of blood samples from Ebola patients in Guinea.

They are tracking how the virus is changing and trying to establish whether it's able to jump more easily from person to person

"We know the virus is changing quite a lot," said human geneticist Dr Anavaj Sakuntabhai.

"That's important for diagnosing (new cases) and for treatment. We need to know how the virus (is changing) to keep up with our enemy."

It's not unusual for viruses to change over a period time. Ebola is an RNA virus - like HIV and influenza - which have a high rate of mutation. That makes the virus more able to adapt and raises the potential for it to become more contagious.

"We've now seen several cases that don't have any symptoms at all, asymptomatic cases," said Anavaj Sakuntabhai.

"These people may be the people who can spread the virus better, but we still don't know that yet. A virus can change itself to less deadly, but more contagious and that's something we are afraid of."

Latest figures

There were fewer than 100 new cases in a week for the first time since June 2014.

In the week to 25 January there were 30 cases in Guinea, four in Liberia and 65 in Sierra Leone.

The World Health Organization says the epidemic has entered a "second phase" with the focus shifting to ending the epidemic.

But Prof Jonathan Ball, a virologist at the University of Nottingham, says it's still unclear whether more people are actually not showing symptoms in this outbreak compared with previous ones.

"We know asymptomatic infections occur… but whether we are seeing more of it in the current outbreak is difficult to ascertain," he said.

"It could simply be a numbers game, that the more infection there is out in the wider population, then obviously the more asymptomatic infections we are going to see."

The current outbreak began in south-eastern Guinea and spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone

Another common concern is that while the virus has more time and more "hosts" to develop in, Ebola could mutate and eventually become airborne.

There is no evidence to suggest that is happening. The virus is still only passed through direct contact with infected people's body fluids.

"No blood borne virus, for example HIV or Hepatitis B, has ever shown any indication of becoming airborne. The mutation would need to be major," said infectious disease expert Professor David Heyman.

Virologist Noel Tordo from the Institut Pasteur is in the Guinea capital Conakry. He said:

"At the moment, not enough has been done in terms of the evolution of the virus both geographically and in the human body, so we have to learn more. But something has shown that there are mutations.

"For the moment the way of transmission is still the same. You just have to avoid contact (with a sick person).

"But as a scientist you can't predict it won't change. Maybe it will."

Researchers are using a method called genetic sequencing to track changes in the genetic make-up of the virus. So far they have analysed around 20 blood samples from Guinea. Another 600 samples are being sent to the labs in the coming months.

A previous similar study in Sierra Leone showed the Ebola virus mutated considerably in the first 24 days of the outbreak, according to the World Health Organization.

It said: "This certainly does raise a lot of scientific questions about transmissibility, response to vaccines and drugs, use of convalescent plasma.

"However, many gene mutations may not have any impact on how the virus responds to drugs or behaves in human populations."

'Global problem'

The research in Paris will also help give scientists a clearer insight into why some people survive Ebola, and others don't. The survival rate of the current outbreak is around 40%.

Prof James Di Santo explains the work being carried out to try to find an Ebola vaccine

It's hoped this will help scientists developing vaccines to protect people against the virus.

Researchers at the Institut Pasteur are currently developing two vaccines which they hope will be in human trials by the end of the year.

One is a modification of the widely used measles vaccine, where people are given a weakened and harmless form of the virus which in turn triggers an immune response. That response fights and defeats the disease if someone comes into contact with it.

The research may explain why some people survive Ebola and others do not

The idea, if it proves successful, would be that the vaccine would protect against both measles and Ebola.

"We've seen now this is a threat that can be quite large and can extend on a global scale," said Professor James Di Santo, and immunologist at the Institut.

"We've learned this virus is not a problem of Africa, it's a problem for everyone."

He added: "This particular outbreak may wane and go away, but we're going to have another infectious outbreak at some point, because the places where the virus hides in nature, for example in small animals, is still a threat for humans in the future.

"The best type of response we can think of… is to have vaccination of global populations."