'Three-person babies - not three-parent babies'

- Published

Prof Doug Turnbull said developing the technique had been a "massive team effort"

On Tuesday, MPs will decide whether to allow the creation of babies from three people - mum, dad and a second, donor, woman.

It could prevent deadly mitochondrial disease, but has provoked a fierce ethical debate.

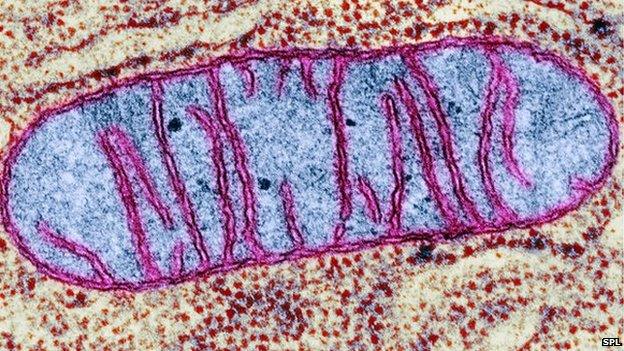

DNA for mitochondria - tiny compartments within cells which unlock the energy from food - is passed from mothers to children, so a donor woman's mitochondria might stop the disease.

Prof Doug Turnbull, head of the centre in Newcastle that has pioneered the research, said the disease affects organs that are "heavily dependent on energy metabolism".

"So in the heart you have cardiac failure; progressive weakness in the muscles leading to extreme fatigue and respiratory failure; and in the brain, epilepsy, stroke-like episodes and cognitive decline," he said.

"In the most severe cases I've looked after, the children died in the first 48 hours of life.

"That is unusual; often these conditions are associated with increasing levels of disability.

"I saw a patient on Tuesday that I've looked after for 33 years."

That patient was one of Prof Turnbull's first when he started out in the field as a young neurologist, "fascinated" about understanding, diagnosing and - more recently - preventing the disease.

Sharon Bernardi, from Sunderland, has lost all seven of her children - including Edward in 2011

The centre in Newcastle sees patients from across the UK and is acknowledged as one of the best in the world for caring for people with mitochondrial disease.

Yet even with the best available medicine there are many heartbreaking stories, including those of families who have lost multiple children.

Six of Sharon Bernardi's children died within days of birth.

Her son Edward survived to the age of 21, although he was often ill.

Prof Turnbull said the huge desire of families to have healthy children motivated the team at the Newcastle centre.

"We've been discussing it since 2000," he said.

"It was the stories of the patients the whole team saw over the years that made us go 'Look, we've got to do better'.

"We have very limited treatments, so the most important thing for those families is to have children that are unaffected."

The idea featured in a report by the UK Chief Medical Officer, external that year, and the Newcastle team's first application for funding was made in 2001.

What emerged at Newcastle was a massive team effort between fertility experts, doctors caring for patients and experts in the genetics of mitochondria.

Their objective was to reach a point where healthy DNA from parents could be combined with healthy mitochondria from a donor.

The proposed therapy - called pronuclear transfer - is controversial.

Last week the Catholic and Anglican churches urged UK politicians to delay their decision to allow more research and debate.

The destruction of embryos as part of the process is among the ethical concerns raised.

Others say it is a first step towards creating so-called "designer babies", where genetic characteristics could be chosen by parents.

Defective mitochondria leave the body unable to produce enough energy

In pronuclear transfer, the mother's egg and the donor's egg are both fertilised as part of IVF to create a pair of embryos.

The DNA from mum and dad form two balls of genetic information in the embryo called pronuclei, which will fuse to create the genetic blueprint for a child.

These are transferred to the donor embryo, which is packed with healthy mitochondria and has its pronuclei removed.

The Newcastle research passed a significant barrier in 2010.

The group published a study in the journal Nature, external showing the technique was possible using eggs that would have been discarded as they were unsuitable for IVF.

"When we published that paper there was a recognition that... if we can make this work with abnormal eggs surely we should be moving forward with this," Prof Turnbull said.

He credits his colleague Prof Alison Murdoch, from the Newcastle Fertility Centre, for having the foresight to begin making the case for starting the process that could lead to a change in the law.

"She was very wise at the time, she said we could get the science finished, but if we don't push forward with trying to get the regulations through Parliament then we could get the science sorted and it could take years to go through," he said.

This is one of many times Prof Turnbull diverts the attention to colleagues - particularly to Prof Mary Herbert, another leader in the field of mitochondrial transfer.

He comes across as a man keenly aware he needs to make the case, but unwilling to be the centre of attention.

"An awful lot of expertise has to go into developing anything like this, this is a massive team effort," he said.

"This has never been about the scientist, it's about the patients."

Imminent decision

The 2008 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, external left provision for babies to be "created from material provided by two women".

But it required a debate and a vote in both the Commons and the Lords for it to be enacted.

Five years, three scientific reviews and a public consultation later, the UK is about to decide.

"The whole process has been suitably rigorous and the UK should be suitably proud of its ability to regulate in such a sensitive area," Prof Turnbull said.

However, there was a sense of frustration in his voice when I suggested things had progressed quickly since 2010.

"It was first mooted in 2000, discussed extensively prior to the 2008 act, a lot of the ground work was done in 2010," he said.

"Is that quick?"

Two mums?

Any child born through this technique would have about 99.9% of their DNA from their parents.

But mitochondria have their own DNA, so that 0.1% would come from the donor, external.

It has given rise to the headline that frustrates many in the field: "Three-parent babies".

Prof Turnbull responds: "We know precisely what those genes do.

"Those mitochondria are not going to influence any of the characteristics of these children, they're going to provide healthy mitochondria. But it's a catchy headline.

"Do I think it's accurate? Of course I don't.

"Is there anything I can do about it? Even less," he concludes with a resigned chuckle.

But the headlines point to a deeper issue.

The change to the child's genetic composition will be passed down through the generations.

It is known as germ-line therapy and is illegal in many countries.

Some argue we are sleep-walking into a society that allows these techniques, external and opening the door to other forms of genetic modification of children.

I put these arguments to Prof Turnbull.

"I think people are perfectly entitled to their view, I've always felt that," he said.

"That the critics say 'I wouldn't have this' is of course reasonable, but I think the thing we all struggle with here at Newcastle is that they are denying other people the right to make those sorts of decisions.

"When you talk to patients with mitochondrial disease they want to make those decisions."

If the vote in the Commons goes through on Tuesday, and the House of Lords agrees in the coming weeks, the UK fertility regulator could grant Newcastle the first license this year.

The first attempt would then be expected this year, with the first baby born in 2016.

Prof Turnbull admits to being a "natural pessimist" and says he is "anxious" ahead of the vote by MPs.

His final argument is: "This is research that has been suggested by the patients, supported by patients and is for the patients, and that's an important message."

- Published30 January 2015

- Published29 January 2015

- Published17 December 2014

.jpg)

- Published3 February 2015

.jpg)