Living at home with dementia

- Published

We are aware that this interactive video may not work on some older browsers. You can find a non-interactive version of the content below.

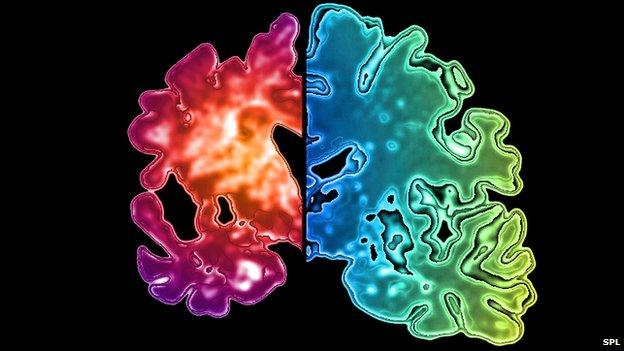

More than 525,000 people with dementia in the UK are living at home, the Victoria Derbyshire programme has learned.

The estimated figure, provided by the Alzheimer's Society, represents a significant proportion of the 850,000 people thought to be living with the condition overall.

This is the case for Wendy, Keith and Christopher. Having had Alzheimer's disease - the most common form of dementia - for different lengths of time, their stories depict how the condition can progress over the first seven years.

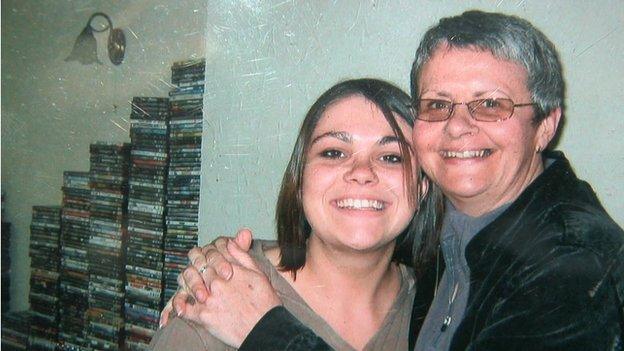

Wendy's story: One year since diagnosis

Standing outside her office, in a familiar corridor, Wendy Mitchell lost all sense of where she was.

At 57, she was experiencing her first clear sign of what was to later be diagnosed as early onset dementia.

"That was just mind-blowingly frightening, because there you are one minute, knowing exactly where you are and who you are, and suddenly your mind is empty."

Since then, the biggest change has been to her working life.

"I wanted to continue working but as time has gone on, I realised that I was not able to do the things that I once could," she says.

"I used to juggle 10 jobs at once - answer the phone, be on the computer, talking to people. I can't do that any more."

Wendy Mitchell relives the moment of her first significant memory loss

Retiring from her non-clinical role in the NHS has allowed Ms Mitchell more time to spend time with her family, write her blog, external and support the work of the Alzheimer's Society - going to conferences and taking part in medical trials.

"Just being part of that research makes me feel of value. You lose a lot of feeling of value when you are diagnosed with Alzheimer's [disease]."

But Ms Mitchell has also had to prepare for the future, putting together a "memory room" of photos that hold special meaning.

"Once I lose who's who in all the pictures and forget the destinations, I am sure I will be able to stand in this room and feel happiness," she explains.

One of her greatest fears is not being able to recognise her two daughters.

"I've said to them that one day you'll come in the room and I won't know who you are, I won't know your name.

"But I'm sure I'll feel that emotional connection of love that we have for each other, and [they will] always remember - that although I won't recognise them - I'll still love them."

Watch Victoria Derbyshire weekdays from 09:15-11:00 BST on BBC Two and BBC News Channel, for original stories, in-depth interviews and the issues at the heart of public debate.

Follow the programme on Facebook, external and Twitter, external, and find all our content online.

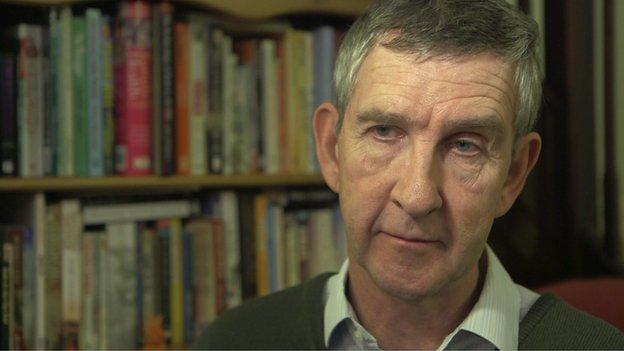

Keith's story: Four years since diagnosis

"People say to me 'well, sometimes we hardly know you have dementia', and that's true - on good days I cope very, very well.

"On other days I'm less good, but they're the days I tend to draw into myself so that people from outside don't see me."

Keith Oliver, 58, was a primary school head teacher when he was diagnosed four years ago. Now he says he is experiencing more "foggy days" than previously, and skills he once took for granted like remembering words do not come as easily.

Mr Oliver had been a primary school teacher for over 30 years

He turned down the offer of anti-depressants, instead finding friends, family and a local support group increasingly important.

"That is what lifts the fog for me. It makes me feel I'm being listened to. The love of family helps considerably in slowing down [the effects of dementia]."

But he wishes to shield loved ones from the "blacker side" of the disease as his condition worsens.

"One doesn't want them to feel sorry for me. I don't want them to be frightened. I don't want the disease to come between what is a very loving relationship within a family."

Mr Oliver believes dementia has changed the way he feels about, and interacts, with other people.

"It's made me more reflective. Made me a more emotionally-aware person. Made me, I guess, less distant from people.

"My interactions, particularly at work, would revolve around a professional approach. I would always treat everyone the same - speak as a professional would. Now I find that any interaction tends to be an emotional experience.

"I don't remember what the person said, but [the conversation] does leave me with a feeling of how the person made me feel."

Dementia in the community

An estimated 525,000 people in the UK are living with dementia at home, a significant proportion of the 850,000 with the condition overall.

There are 670,000 carers of people with dementia in the UK.

Family carers of people with dementia save the UK £11bn a year.

In a survey of 1,000 people living with dementia, almost one in 10 said they only leave the house once a month.

Source: Alzheimer's Society, external

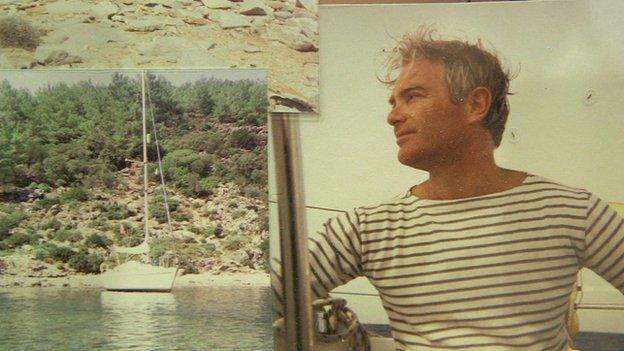

Christopher's story: Seven years since diagnosis

Christopher Devas's fading short-term memory means it is now rare for his wife, Veronica, to leave him on his own.

"We don't do anything apart really," she explains. "If I was to go out and leave him lunch then he wouldn't [remember to] eat it."

Mr Devas, now 70, was a magistrate and mediator for people bullied in the workplace when he first realised "things were not quite right".

Back then there was a stigma surrounding the disease, but his wife says that now "people are not shocked in the bank if I say 'my husband has Alzheimer's, can you speak more slowly?'"

This wider acceptance has made it easier to tackle what she believes is one of the greatest consequences of dementia - boredom.

"If you have a hobby you can carry on with, then carry on, keep going with it - do things that people who don't have Alzheimer's do. Meet people."

Christopher Devas struggles to remember the word "moon" when on a walk with his wife

While social events have become more difficult over time, she makes sure her husband is "primed and ready" with the names of all those attending, so as not to offend.

Over time, Mr Devas has also increasingly struggled to remember nouns, which causes some difficulties.

"We do have some quite funny things. I'll say 'can you get the fork, it's round the other side of house', and what comes back isn't the fork."

There is one simple technique, however, that is having a positive effect.

"I take photos of everybody now, and for some reason a photo seems to stick [in the mind]," explains Mrs Devas.

"If I said to him 'do you remember those wonderful sailing holidays', I think he would find it difficult. But if you present the photos he would remember."

For Mr Devas, though, his declining memory is not something that frightens him.

"I've done that [what has happened in the past]. There's always something going forward," he explains.

"You keep going, I'm not going to stop."

Catch up with the full film online, from the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme.

- Published6 March 2015

- Published21 February 2015

- Published15 January 2013