Ebola 'more deadly' in young children

- Published

Ebola is more deadly for young children than adults, an analysis in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests.

Scientists found 90% of babies under one suspected to have the virus died - compared to some 65% of adults across Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Children are overall much less likely to catch the virus, but researchers say there is an urgent need for specialist care to meet their differing needs.

Meanwhile, a vaccine trial involving adult volunteers has begun in Guinea.

Viral differences

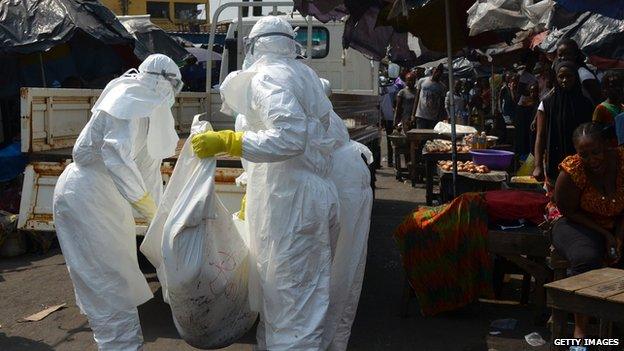

Ebola has killed more than 10,000 people across the three worst-affected countries of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia in the last 12 months.

The majority have been adults - just one in five deaths involves a child under 15. But this outbreak has seen the highest number of young people infected of any in history.

By analysing data collected by local ministries of health and the World Health Organization, scientists were able to uncover previously unknown clues revealing how the virus affects different ages in distinct ways.

According to their records, which span from the beginning of the outbreak to January 2015, about 80% of children under five with probable or confirmed Ebola died.

And the illness progressed more quickly in the young - they showed signs of the disease 72 hours before most adults did.

Prof Christl Donnelly from Imperial College London, who was involved in the study, said: "It is especially important that we get young children into treatment quickly.

"We also need to look at whether young children are getting treatment appropriate for their age."

In contrast the study suggests that older children - from the age of 10 to 15 - had a lower fatality rate than adults.

Scientists say more research is needed to unpick the likely multiple reasons why all these differences exist.

They suggest babies may be more vulnerable to dehydration, for example, and therefore need fluids more quickly through a drip.

Ring vaccination

But there is still no specific drug treatment proven to work against Ebola.

In collaboration with the Public Health Agency of Canada and the company Merck, scientists in Guinea are working on a vaccine to protect those most at risk.

Their strategy involves vaccinating anyone who has come into contact with recently-infected patients to create a ring of potential protection.

Dr Bertrand Draguez, from the charity Medecins sans Frontieres, which is involved in the trial, said people would take part on a voluntary basis.

Results could be available as early as July.

Other vaccine trials are under way in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Public Health England has also announced a £1m grant to develop a rapid field kit for the disease.

It aims to generate a test which diagnoses suspected cases within 40 minutes.