What drives people to murder-suicide?

- Published

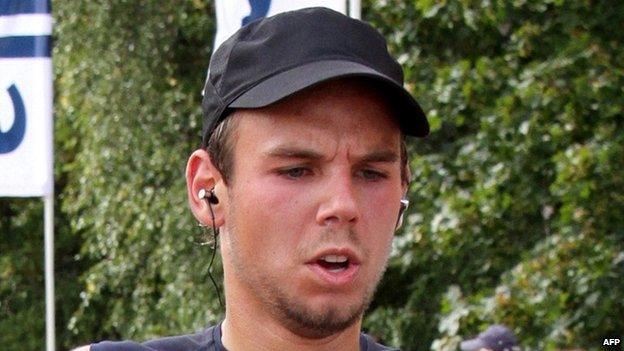

Only Andreas Lubitz will ever know for sure why he flew a plane into an Alpine hillside, killing 150 people

The question has been raised - is 27-year-old Andreas Lubitz a mass murderer for bringing down a plane full of passengers, killing everyone on board?

Reports of a "mass murder" investigation in France and pictures of German policemen carting bags of evidence from his parents' home suggest that officials are determined to find out.

But this appears to be a case of murder-suicide, which is very different and extremely rare.

In these incidents, one person wishing to end their life takes the lives of others - in this case, complete strangers - at the same time.

The statistics show that most murder-suicides happen in domestic settings, and involve a man and his spouse.

Murder-suicides involving pilots or in gun massacres are, in fact, much, much rarer.

What drives people to these acts is therefore virtually impossible to determine because there is no common theme and the perpetrators don't leave notes explaining their actions.

In contrast to the motivations of a suicide bomber, which are intentionally well-publicised, those behind a murder-suicide are usually more difficult to fathom.

No-one, of course, can pretend to know what was in Lubitz's mind as he locked the cockpit door and instigated the plane's devastating descent.

'Inexplicable'

Simon Wessely, president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, says it's unlikely we will ever know.

"It's possible something will emerge, but in most suicides people leave clues or a message.

"Incredibly extreme events like this are sometimes just inexplicable."

Despite this, the media has been quick to point the finger at Lubitz's history of depression.

German newspapers have also reported that he had received psychiatric treatment and may have been experiencing a "personal life crisis".

In reality, there is a multitude of factors, feelings and personality traits which could push someone to such an extreme course of action.

Alcohol problems, drug misuse, broken relationships or marriages, personality disorders, work stresses - in the past or at the time of the act - can all play a part.

Mental health charities agree, and have been queuing up to plead for more understanding about depression, and less sensationalist language.

They say the vast majority of people with depression do not hurt anyone, and research shows that their risk is primarily to themselves.

Stigma danger

Marjorie Wallace, chief executive of mental health charity Sane, says: "There are thousands of people with a diagnosis of depression, including pilots, who work, hold positions of high responsibility and who present no danger whatsoever.

"We do not know what part depression played in this tragedy but it is a condition that should never be trivialised."

Charities said there was a danger that mental health problems could be stigmatised by coverage of the crash, making people more afraid to talk about their experiences.

Dr Paul Keedwell, consultant psychiatrist and specialist in mood disorders, also says mental health problems are not a sufficient explanation for what happened.

"Among cases of murder-suicide in general, the rate of previously diagnosed depression varies from 40% to 60%, depending on the context."

But he does say that of those who are depressed, very few are being treated for it.

It is clear that men find it particularly difficult to seek help if they have a history of mental illness.

In the UK, for example, 75% of suicides are in men.

Lubitz passed the tests set by his employer which indicated he was fit to fly, but it has since come to light that he may have been hiding an illness from them.

This illness and his seeming inability to talk about it or come to terms with it may hold some small clue to his actions.

But, in reality, there is never going to be an adequate explanation for murder-suicides - particularly for the families of those killed.

- Published27 March 2015

- Published23 March 2017

- Published6 May 2015