Battling a hospital superbug at Queen Elizabeth in Birmingham

- Published

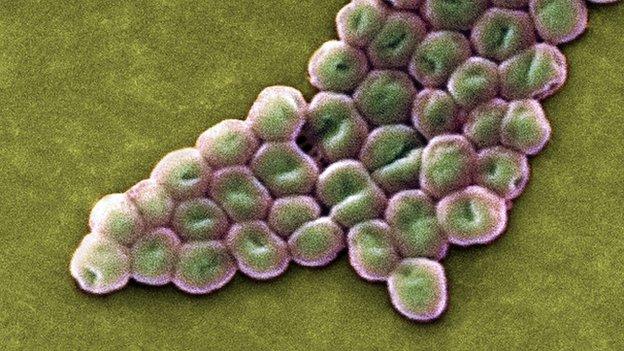

Acinetobacter baumannii has developed resistance to a number of antibiotics and is increasingly seen in opportunistic infections in hospitals.

It took the Queen Elizabeth hospital in Birmingham 18 months to eradicate a particularly nasty strain of superbug that was infecting patients on some of its wards.

Before then the Acinetobacter baumannii bug managed to resist nearly everything staff and cleaners threw at it.

But what makes the bug so tough and why is it difficult to get rid of?

It doesn't look like there's much inside the Petri dish in the laboratory at Birmingham University's microbiology department.

But somewhere on the surface of the container is a relatively new strain of a superbug called Acinetobacter baumannii.

Although invisible to the naked eye it is potentially deadly to hospital patients who get it.

It tends to infect people who are already sick and have a weakened immune system.

Typically it manages to attack the lungs leading to a form of pneumonia. Some microbiologists believe it kills nearly a third of people it infects.

As with other hospital born superbugs it is hard to treat and difficult to get rid of.

"It's like other bacteria which we call gram negative bacteria, " says the department head Prof Laura Piddock.

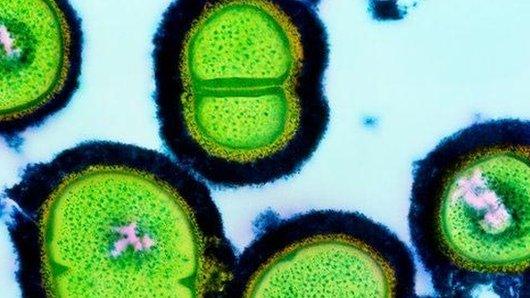

"They are tough because they have in the cell two membranes and it's like two barriers to the outside world - so antibiotics have to get in across these two barriers and stay inside the cell to be able to kill the bacterial cell."

However, even if antibiotics do manage to break through its outer defences the superbug has a last line of defence.

It has its own built in 'bacterial vacuum cleaner' that automatically sucks out the antibiotics.

Professor Laura Piddock is head of Birmingham University's microbiology department

"It's a bit of a double whammy with this kind of bacteria. They don't let very much in and what gets in, most of it is promptly vacuumed out again," says Prof Piddock.

New bug

The Acinetobacter bug was first identified in the Queen Elizabeth hospital in 2011.

Some media reports suggested injured British and American soldiers brought it back to the US and UK after becoming infected while serving in Iraq.

Some doctors are not convinced about this, but what they do know is that the bug is now able to survive in UK hospitals.

Few know more about that than the Queen Elizabeth hospital in Birmingham, just 400m down the road from Prof Piddock's laboratory.

The hospital opened in June 2010 and was designed to meet strict hygienic standards.

It was designed with no nooks and crannies to harbour dirt or bacteria so as to make it easy to clean.

However, shortly after the hospital opened it was hit by a particularly nasty outbreak of Acinetobacter baumannii.

In total 52 patients ended up contracting the bug.

The critical care unit of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital treats service personnel injured overseas

"We did all the normal things that you would expect including improving hand hygiene, cleaning, tracking down patients that had it and separating them from other people," says Dr Beryl Openheim.

For the last three years she has been working on infection control for the university hospitals in Birmingham.

"Disappointingly, despite that, it kept coming back - it kept cropping up in patients you hoped wouldn't be carrying it.

"It's worth saying at this point that this bacterium is very sticky. It likes sticking to patients' wounds and we know it also likes sticking to surfaces in the environment," she says.

Stubborn

Altogether the outbreak lasted 18 months and it was only eradicated after the closure of an operating theatre which had to be decontaminated with hydrogen peroxide.

"It's particularly known for the fact it's so difficult to get rid of. It can live on surfaces like a table or a bed and so it just had this predilection for surviving in a hospital environment where antibiotics are being splashed around."

"If you give antibiotics, you select for antibiotic resistant organisms, the sensitive ones die off and the ones left standing take over and multiply."

The threat posed by antibiotic resistant bacteria like Acinetobacter baumannii is now on Britain's official National Risk Register.

That means they are rated alongside terrorism, civil disorder and cyber-attack as a realistic potential danger we need to prepare for and deal with.

A government commissioned review, external recently warned that, unless action is taken, antibiotic resistant infections could kill an extra 10 million people a year worldwide by 2050.

They are currently implicated in 700,000 deaths globally each year.

Listen again to The Report, first broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 7 May 2015.

- Published11 December 2014

- Published11 October 2012

- Published9 November 2011