How safe is air quality on commercial planes?

- Published

Seventeen former and serving cabin crew are planning to take legal action against British airlines because they say contaminated air inside plane cabins has made them seriously ill, the Victoria Derbyshire programme has learned.

Figures from the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) show that since 2010 they have received more than 1,300 reports of smoke or fumes inside a large passenger aircraft operated by a British airline.

But is there evidence to suggest air quality on flights can pose a serious health risk? We examine the evidence.

What is being criticised?

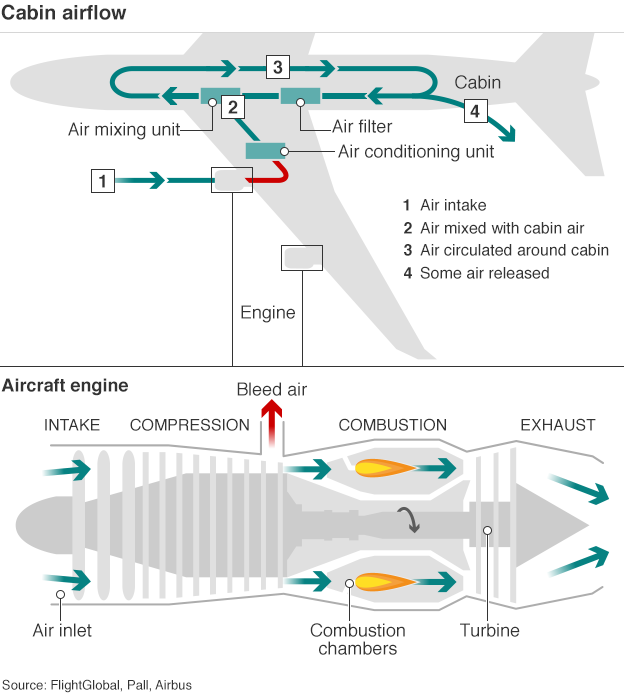

At the altitude at which commercial jets fly, the air pressure does not allow humans to breathe independently.

To overcome this, hot compressed air is drawn from the plane's engines and, once cooled, directed into the cabin to supply breathable air - known as bleed air.

This does not pose a health risk in itself. But campaigners believe that potential faults in the engine seals can lead to heated engine oil, hydraulic fluids and harmful chemicals called organophosphates - used to lubricate the engine's metal parts - contaminating the air.

They claim this can cause negative health consequences in both the form of fume events - one-off instances where oil fumes from the engine move into the cabin - and long-term, low-level exposure from frequent flying. The only exception being the new Boeing 787, which uses "bleed-free technology".

These health effects are known to campaigners as "aerotoxic syndrome", but British airlines and the CAA maintain there is no scientific evidence that shows the condition exists.

How often do fume events take place?

Prof Alan Boobis, director of Public Health England's Toxicology Unit at Imperial College London, estimates fume events take place in "one in every 2,000 [British] flights". As a result, he says, studies have never been able to record one.

He adds that the information available indicates even during potential fume events, levels of air contamination "are low, and probably below those which would be affecting health in humans".

According to safety reports submitted to the CAA, there were 251 incidents of fumes or smoke in the cabin between April 2014 and May 2015.

These figures just apply to UK airlines so would not include any fume event reported by Lufthansa or Ryanair for example, even if they took place in British airspace.

Where possible, the BBC has stripped out cases which were clearly the fault of broken internal equipment like toilets and air conditioning systems.

Dr Jenny Goodman from London's Biolab Medical Unit, who has treated many crew members, says she has heard anecdotal accounts from airline staff of "old stinkies" - planes in which the cabin fills with fumes every time they start up the engine.

Although the smoke evaporates in such instances by the time passengers go on board, she explains, cabin crew are nevertheless exposed to the contamination.

Does the risk of illness increase with time spent flying?

Dr Goodman believes the risk for health complications is particularly great for airline staff and frequent flyers. "If you fly regularly, or fly as part of your job, you're going to have exposure to constant low-level leakage, which you may or may not be aware of," she explains.

She adds that those on long-haul flights are also more susceptible to illness, when taken regularly: "You're stuck there for hours and hours. You're breathing far more concentrated levels of these substances, and a far greater level of them."

Aviation lawyer Frank Cannon believes pilots and cabin crew are at greatest risk, and as a result of exposure to contaminated air could become unfit to fly. He believes in some instances pilots may be willing to hide cognitive dysfunction or memory deficits caused by the poor air quality for fear of losing their jobs, which puts others at risk.

In other instances, he says, pilots may not be aware of the symptoms, meaning they similarly continue to fly while unsafe to do so.

Prof Boobis says the possibility of long-term health effects from repeated exposure to fume events is an area that needs more research.

What are the symptoms?

Dr Goodman says aerotoxic syndrome affects the central nervous system and brain in particular. While genetic variation means not all people suffer symptoms, the nature of the chemicals present in contaminated air means they can "dissolve in our cell membranes, get into our cells and therefore get into every system in the body".

She says this can lead to wide-ranging symptoms including migraines, fatigue, difficulty thinking, aches and pains in joints and muscles, breathing problems, digestive problems and even an increased risk of breast cancer for women. She adds that many GPs fail to see the link to frequent flying and wrongly prescribe anti-depressants.

Dr Goodman says aerotoxic syndrome can have serious effects on the central nervous system and brain

But Prof Boobis believes levels of chemicals in the cabin following a leakage are "similar to a normal home or workplace", and do not pose a serious health risk.

He says the symptoms Dr Goodman describes may instead be the result of a "nocebo effect" - in this instance an individual's false belief that they are being harmed by a chemical after smelling an odour in the cabin, most probably from fuel.

He believes this can lead to "serious health issues" in its own right and should not be ignored. But, he adds, it should not be misconstrued as aerotoxic syndrome.

What can be done in future?

Dr Goodman and Mr Cannon say the industry must ensure filters are fitted to aircraft engines. Mr Cannon notes that there are "two or three different companies" making the filters - including one manufacturer that claims it can prevent 99.9% of the contamination.

They both believe that the principal reason the industry is reluctant to fit the filters is that doing so would be seen as a "tacit admission" that aerotoxic syndrome exists.

A report from the Committee on Toxicity in December 2013, commissioned by the Department of Transport and chaired by Prof Boobis, said there was a "continuing imperative to minimise the risk of fume incidents that give rise to symptoms", whether this be through toxicity or nocebo effects.

The CAA said in a statement: "There is no positive evidence of a link between exposure to contaminants in cabin air and possible long-term health effects - although such a link cannot be excluded."

Watch Jim Reed's full film on cabin air quality on the Victoria Derbyshire website.

- Published8 June 2015