Deafness could be treated by virus, say scientists

- Published

Scientists say they have taken a significant step towards treating some forms of deafness after restoring hearing in animals.

Defects in a baby's DNA are behind roughly half of cases of hearing loss in early life.

The mouse study, published in Science Translational Medicine, external, showed a virus could correct the genetic fault and restore some hearing.

Experts said the results could lead to treatments within a decade.

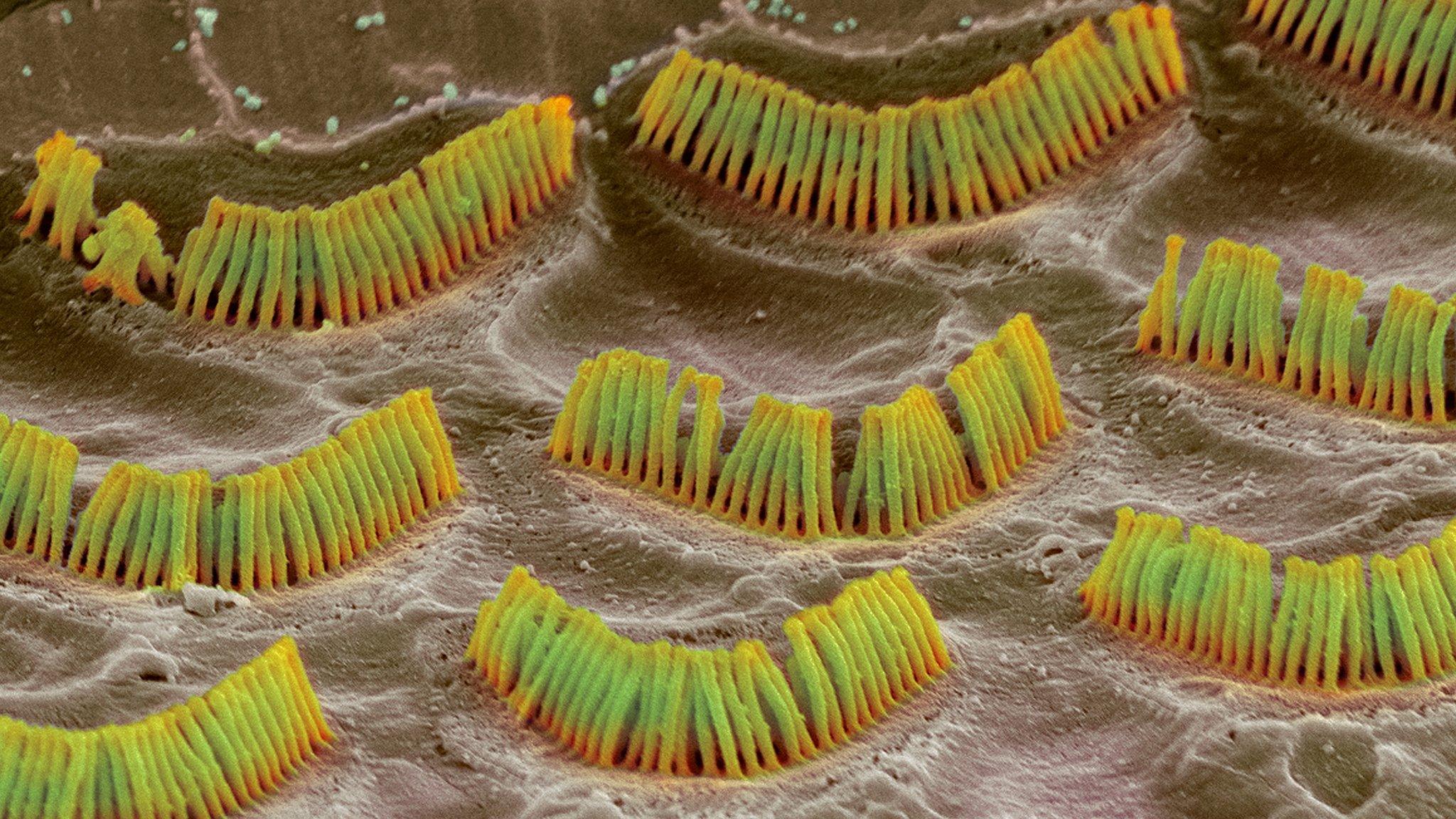

The team in the US and Switzerland focused on the tiny hairs inside the ear, which convert sounds into electrical signals that can be interpreted by the brain.

But mutations in our DNA can leave hairs unable to create the electrical signal - leaving people unable to hear.

Viral therapy

The research team developed a genetically modified virus that could infect the hair cells and correct the error.

It was tested on "profoundly deaf" mice, which would not notice being at a loud rock concert (with sound levels at 115 dB).

Injections of the virus into the ears led to a "substantial improvement" in hearing, although not to normal levels.

The animals could hear the equivalent of the noise inside a moving car (85 dB).

They also altered their behaviour in response to sounds throughout the 60-day study.

The hairs in the ear detect changes in pressure and convert them into electrical signals

Dr Jeffrey Holt, one of the researchers from Boston Children's Hospital, told the BBC News website: "We're very excited about it, but we're also cautiously optimistic as we don't want to give false hope. It would be premature to say we've found a cure.

"But in the not-too-distant future it could become a treatment for genetic deafness so it is an important finding."

The team are not yet ready for human clinical trials.

They want to prove the effect is long-lasting. They know it works for a few months, but are aiming for a life-long change.

The viral therapy alters most of the inner hair cells in the ear, but not the outer hair cells.

The inner hairs allow you to hear sound, but the outer hairs alter the sensitivity to sounds, so the ear becomes more sensitive to faint noises.

Personalised

The study repaired a mutation in a gene called TMC1, which is behind roughly 6% of deafness that is passed through families.

However, there are more than 100 separate genes that have been linked to deafness.

"I can envision patients with deafness having their genome sequenced and a tailored, precision medicine treatment injected into their ears to restore hearing," said Dr Holt.

However, the findings will not benefit adults who have hearing loss as a result of listening to too much loud music.

Commenting on the findings, Dr Tobias Moser from University Medical Center Gottingen in Germany said the results were "promising".

The study provided "hope that restoration of hearing will become available for select forms of deafness within the next decade".

UK scientists Prof Karen Steel, from King's College London, said: "I think this paper represents a really exciting advance in our understanding of what could be achieved using gene transfer approaches into the inner ear to reduce the impact of damaging mutations.

"At the moment, the function is only partially rescued, but this is a start and presumably the methodology could be developed to improve the outcome."

Dr Ralph Holme, the head of biomedical research at the charity Action on Hearing Loss, said: "The genetic diagnosis of hearing loss has greatly improved in the last few years, enabling children and their families to understand the cause of their deafness and predict how it may change over time. However, treatments are still limited to hearing aids and cochlear implants.

"These findings are encouraging and open the door for other gene therapies, providing hope for people with certain types of genetic hearing loss that, following diagnosis, gene therapy could be available in the not-too-distant future."

- Published10 January 2013

- Published12 September 2012