What is polonium-210?

- Published

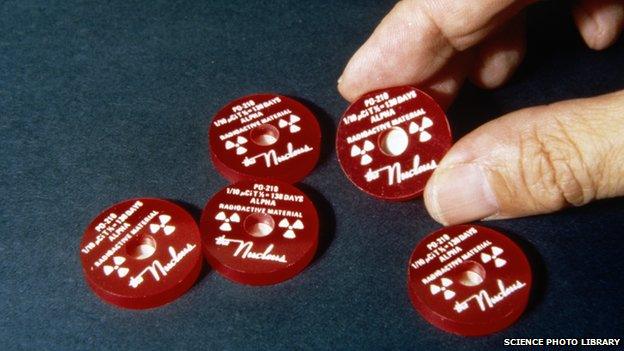

Polonium is used in very small quantities in some industrial applications

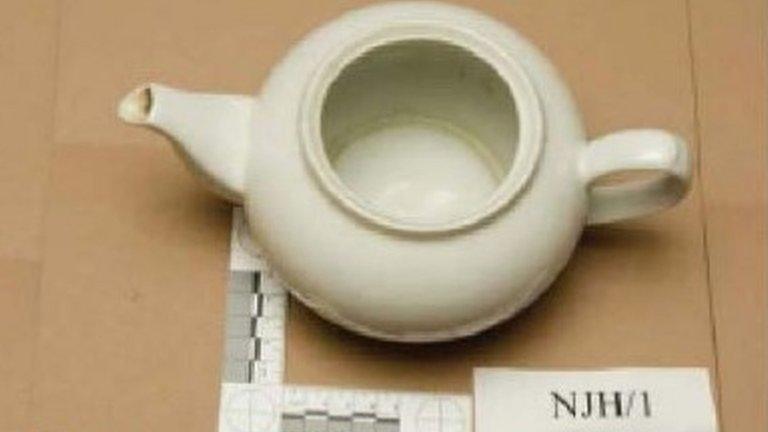

Polonium has been at the centre of the inquiry into the death of former Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko in November 2006 in London.

He was poisoned by a "major dose" of the radioactive substance polonium-210, contained in a cup of tea, killing him three weeks later.

When ingested, the poison is deadly and very difficult to identify.

What is polonium-210?

It is a naturally occurring radioactive material that emits highly hazardous alpha (positively charged) particles.

It is one of 25 radioactive isotopes of polonium, a silver-coloured metal found in uranium ores.

The Polish-French scientist Marie Curie first discovered polonium at the end of the 19th Century.

There are very small amounts of polonium-210 (Po-210) in the soil and in the atmosphere, and everyone has a small amount of it in their body.

But at high doses, it damages tissues and organs. A microgram of Po-210, about the size of a speck of dust, would be certain to deliver a fatal dose of radiation if swallowed.

Marie Curie and her husband Pierre's research unearthed a new element called polonium

However, the substance, historically called radium F, is very hard for doctors to spot once it's in the body.

Is there a risk to other people?

Polonium-210 must be ingested or inhaled to cause damage - breathing it in, taking it into the mouth or getting it into a wound.

And because the radiation has a very short range, it harms only nearby tissue.

It cannot pass through skin, paper or clothes, for example.

However, there was a theoretical risk that anyone who came into contact with the urine, faeces, sweat and tears of Mr Litvinenko could have ingested a small amount of the polonium.

What is polonium-210 normally used for?

It is used to eliminate static electricity in some industrial processes and as a power supply in nuclear weapons production, and in the oil industry.

Russian lunar landers used it to keep the craft's instruments warm at night.

But is not available in these industries in a form that makes it easy to use as a poison.

Experts say that to poison someone, much larger amounts would be required and this would have to be man-made, perhaps from a particle accelerator or a nuclear reactor.

Polonium-210 gives off very dangerous alpha particles, which are capable of destroying human organs

Where would someone get it from?

Although it occurs naturally in the environment, acquiring enough of it to kill would require individuals with expertise and connections.

It would also need sophisticated lab facilities - and access to a nuclear reactor.

Only around 100g of polonium-210 is made in nuclear reactors each year around the world.

Alternatively, it could have been obtained from a commercial supplier but this would be near impossible without arousing suspicion.

Polonium-210 can either be extracted from rocks containing radioactive uranium or separated chemically from the substance radium-226.

Production of polonium from radium-226 would need sophisticated lab facilities because the latter substance produces dangerous levels of penetrating radiation.

Why is it known as the "perfect poison"?

Because the alpha particles emitted by polonium-210 cannot travel through skin or paper, it would be easy to smuggle a tiny amount into the country in a glass vial.

The substance is also very difficult to detect - in hospital tests and airport scanners - because it emits hardly any gamma radiation, which is what Geiger counters look for.

Polonium has no colour or taste, so could be easily added to food or drink, and when it decays inside the body it continues to cause damage for several weeks or longer.

It is a slow and silent killer that attacks the red blood cells followed by the liver, kidneys, spleen, bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system.

But, on the other hand, polonium does leave traces and can help police to locate those using it by following a trail of contaminated locations.

Has it been linked to any other deaths?

The daughter of Marie Curie died of leukaemia in 1956 and the disease was linked to a laboratory accident that occurred more than a decade before, when a sealed capsule of polonium exploded.

- Published28 July 2015

- Published21 January 2016

- Published27 July 2015