Is this cuddly robot coming to a care home near you?

- Published

Seal of approval: Hugh Pym meets Paro, the cuddly carer

Robots and smart computers are starting to find their way into care homes and schools. They are more manageable than pets and more patient than humans.

Maureen, who is in her late 70s, cuddles what looks like a seal toy. And in one sense it is. But this seal, brand named Paro, is a lot more than a plaything. In effect, it's a highly sophisticated computer covered in artificial fur.

With a basic form of artificial intelligence Paro, designed in Japan, moves in response to being stroked or at the sound of a voice. The result is physical and emotional interaction with Maureen or others holding the seal.

A handful of NHS trusts are experimenting with the use of Paro for the elderly in care homes, some with dementia. The early indications are that the seal can help calm older residents who might be distressed and perhaps remind them of the experience of looking after pets which is no longer possible after moving into residential care.

Meeting Maureen, and Paro

A collaboration between the Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, which cares for people with mental health problems, and the University of Brighton is backing a research project using Paro. The aim is to observe outcomes for patients using the seal.

"For some people he might provoke memories of giving, caring loving," says Dr Penny Dodds, a qualified nurse and lecturer at the University of Brighton. "For other people it might be that he helps soothe and relax and reduce anxiety and distress. We might use him as an alternative to medication to reduce anxiety."

It's early days for robots and healthcare in the UK and until the Sussex research is completed, no definitive conclusions can be reached on their value for the elderly. But researchers say it's conceivable that the seal, which costs about £3,300, could be adopted more widely in the NHS.

Intelligent Machines - a BBC News series looking at AI and robotics

Where health meets education, artificial intelligence is playing a part.

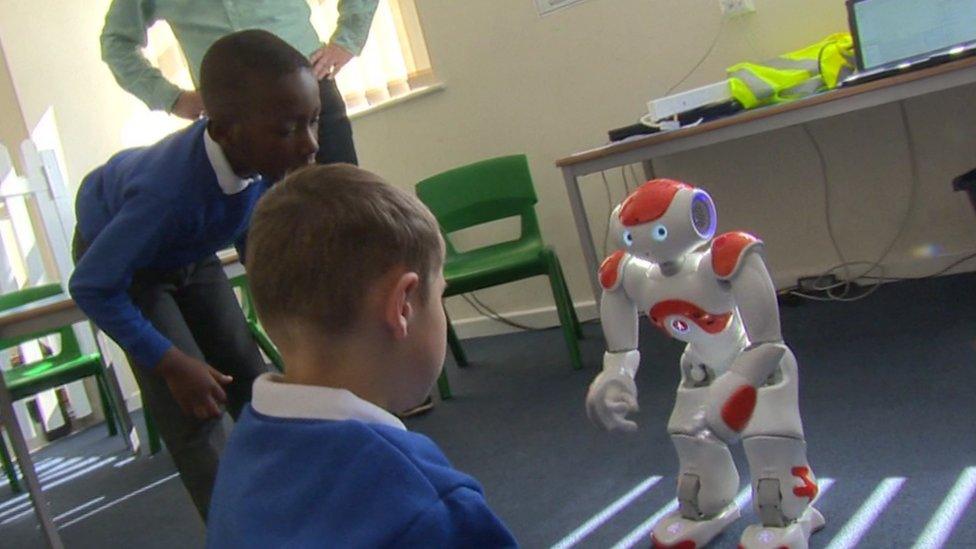

Topcliffe primary school runs a large centre for children with special needs. The teaching staff have been joined by two new recruits: Alexander and Ben.

Instead of heading home after school, however, they go back in their boxes.

They are robots and have proved popular with children with autism.

The knee-high machines can sing songs on request, play word games and listen to pupils reading stories. For children with autism spectrum disorder, communication and social interaction are challenging. The robots can help young people bypass these problems and improve their learning experience.

The school's collaboration with the manufacturer, Aldebaran, is one of the first of its kind in Europe, says Ian Lowe, who, as executive head teacher of Topcliffe, has been involved bringing robots into the school over the past three years.

Shining pupils: Children play with one of two classroom robots

"With a robot, what it offers is that it never gives up," says Mr Lowe.

"It always does the same thing and it always rewards the child. It never tells a child whether it is happy, sad or indifferent, therefore the child is always feeling exactly the same about that learning activity. "

These robots, which some would regard as having a limited demonstration of AI, will be followed by more sophisticated versions still in development. They point to a world of personalised medicine which could transform healthcare in future decades.

Smartphone apps to monitor exercise and heart rate are already familiar to customers. Much less so, in Europe, are devices which can be attached to phones to gather data to be stored and analysed in the cloud.

It may not be long, subject to medical regulation, before blood tests can be carried out by individuals with the results transmitted for analysis via a smartphone. So too breath tests for certain types of cancer and monitoring of heartbeat regularity.

Humans couldn't cope with the vast amounts of data harvested through these devices. Instead the data will be crunched, so the theory goes, by AI computers, enabling smarter analysis of the causes of diseases and links between different symptoms. For the patient there could be warnings via text to visit a doctor if regular test results reveal anything untoward.

David Wood, an expert on mobile telephony, who had senior positions with technology firms Psion and Symbian, is excited about the potential for patients:

"Each of your physiological measurements, they seem quite alright in isolation - but it's the combination of the physiological measurement, such as your heart, your perspiration, various chemicals in your body, these may be noticed by the AI as likely to indicate a particular disease or particular problem pending."

Mr Wood and others of like mind don't believe artificial intelligence can ever replace doctors. Indeed, recent research commissioned by the BBC, ranks "medical practitioner" among the lowest of jobs that risk being replaced by computers over the next 20 years.

But AI could take care of the routine tasks and free doctors to focus on diagnosis and treatment of more complex conditions. It should allow more treatment of patients in their homes rather than in hospitals. At a time of relentlessly rising demand for care and financial pressures, this could be just what the doctor ordered for the NHS.