Work that won Nobel Prize for medicine 2015

- Published

People with swollen legs due to severe lymphatic filariasis

The Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine has been split two ways for groundbreaking work on parasitic diseases.

The research, by William C Campbell, Satoshi Omura and Youyou Tu, has led to drugs to treat diseases affecting more than 3.4 billion people around the world.

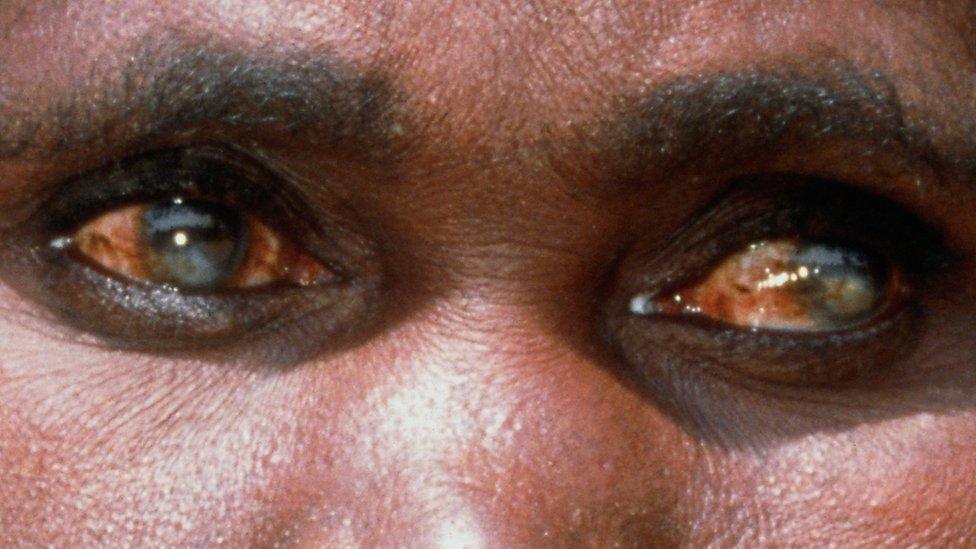

One of them, malaria, most people have heard of. But the other two illnesses, onchocerciasis or "river blindness" and lymphatic filariasis or "elephantiasis" - both caused by roundworm parasites - are lesser known.

Blindness occurs as an allergic reaction when the worms die in or near tissues of the eye

People catch these worms from bites from infected insects such as flies or mosquitoes.

Left untreated, the worms grow and multiply, causing disabling symptoms in their host.

The drug ivermectin kills the first larval stage of the parasite - the babies of adult female worms.

Feeding flies spread the parasite

William C Campbell discovered this by studying bacteria living in soil samples obtained by Satoshi Omura from a Japanese golf course in Ito City, in the Shizuoka region.

One particular strain of bacterium, Streptomyces avermitilis, caught his eye because of its potent anti-parasitic properties.

Working with drug company Merck and Co, he then set about purifying this agent.

Since 1987, Merk (MSD) has given ivermectin away free to those countries that need it most.

Drugs can cure early infection, but advanced disease is harder to treat

Last year, it donated more than 300 million doses to treat river blindness and elephantiasis.

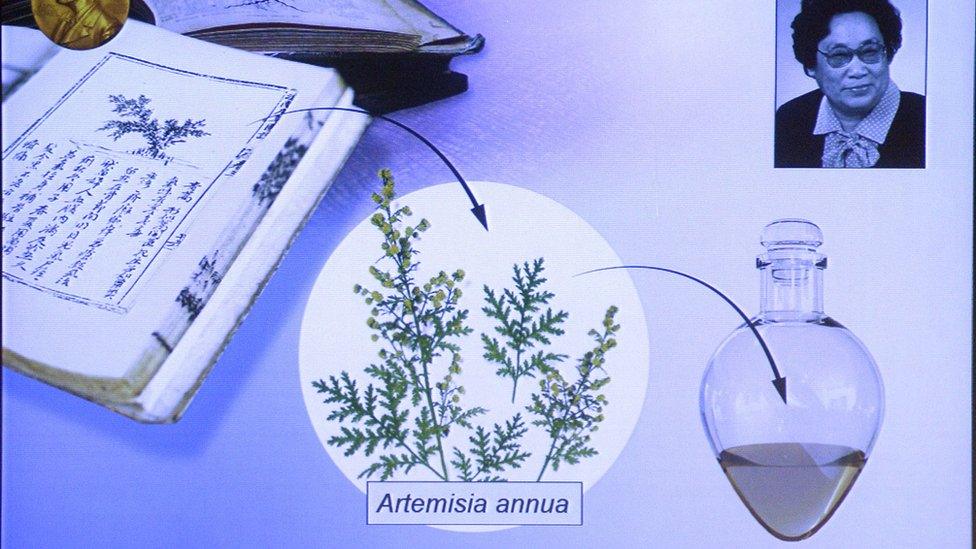

Meanwhile, Chinese scientist Youyou Tu had been focusing her attentions in the 1960s and 70s on finding a new treatment for malaria.

The staples quinine and chloroquine were failing because the parasite that causes malaria - Plasmodium falciparum - had learned how to evade their attack.

Disheartened by the lack of effective drugs to tackle this mosquito-borne disease, the professor turned to traditional medicine to hunt for a new option.

Chinese medicine

She found that an extract from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annual was sometimes effective - but the results were inconsistent, so she went back to ancient literature, including a recipe from AD350.

This ancient document - Ge Hong's A Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies - recommended a handful of qinghao [the Chinese name for the plant extract] immersed in two litres of water, "wring out the juice and drink it all".

This she did (with a few tweaks), testing it on herself as well as animals in her lab.

She said: "During the Cultural Revolution, there were no practical ways to perform clinical trials of new drugs. So, in order to help patients with malaria, my colleagues and I bravely volunteered to be the first people to take the extract.

"After ascertaining that the extract was safe for human consumption, we went to the Hainan province to test its clinical efficacy, carrying out antimalarial trials with patients," she wrote in Nature Medicine, external.

Her discovery eventually led to the creation of an antimalarial drug - artemisinin - that is still relied upon today.

The World Health Organization credits the expanding access to artemisinin-based combination therapies in malaria-endemic countries as a key factor in driving down deaths in recent years.

In 2013, 392 million ACT treatment courses were procured by endemic countries - up from 11 million in 2005.

But artemisinin-resistant strains of malaria are emerging.

As of February 2015, artemisinin resistance had been confirmed in five countries:

Cambodia

Laos

Myanmar, also known as Burma

Thailand

Vietnam

And so the quest for new drugs continues.