Five old remedies that are still healing us today

- Published

A medicinal leech (Hirudo medicinalis)

One of the recent winners of the Nobel Prize for medicine discovered a breakthrough drug after poring over 2,000 ancient herbal recipes.

Dr Tu Youyou's discovery, the anti-malarial artemisinin, derived from wormwood, is credited with saving millions of lives.

From opium in poppies, to quinine derived from the cinchona tree, to digoxin from foxgloves, there are many gems unearthed from the past that have true testable medical benefits.

In fact, there is now a whole branch of science dedicated to the study of traditional medicine, ethnopharmacology.

But it is not as simple as isolating the active ingredient from a plant.

Apart from the fact lots of these plants in their raw form are poisonous, making useful drugs for a population requires planning and sufficient raw material.

"We have to develop drug strategies, and considerations of treating large numbers of people have to be taken into account," Michael Heinrich, professor of pharmacognosy (medicinal plant research) at UCL, says.

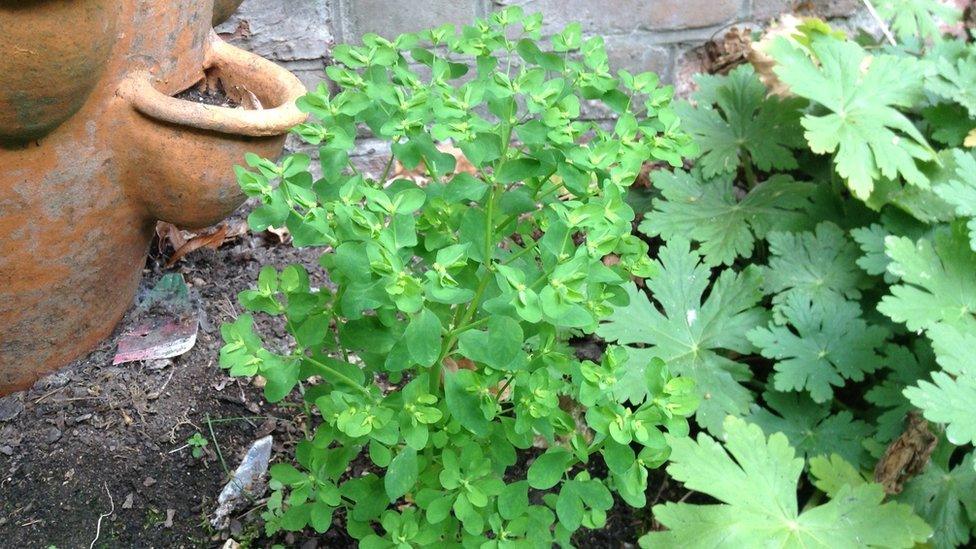

Milkweed

Petty spurge (Euphorbia peplus)

The white sap from this common weed, also known as petty spurge, was described by Nicolas Culpeper's Complete Herbalist (1826) as "a good treatment for warts".

Don't try this at home, however, as its also an irritant.

Milkweed made its way from its native Europe to Australia, where biochemist Dr Jim Aylward had it in his garden.

"My mum grew it for 20 years and swore by it," he says.

"She always told me to put it on my skin to help sunspots."

In 1997, Dr Aylward isolated its active ingredient, ingenol mebutate, which he discovered was toxic to rapidly replicating human tissue.

And recent clinical trials of Picato, a gel derived from milkweed sap, suggest it is effective at stopping lesions turning into skin cancer.

Leeches

Leeches were one of the more civilised methods of bloodletting, a popular cure for disease.

For the Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, any imbalance in the four bodily "humours" (blood, black bile, yellow bile, and phlegm) would cause disease.

And the best way to correct this was to drain the excess - often blood.

Fast-forward to 1830s Europe, and bloodletting was big business.

Use of leeches to treat almost all ailments had reached its peak, with France importing about 40 million every year.

With the rise of "rational" science, and no evidence to back it up, bloodletting died out.

But recent advances in surgery mean leeches are back on the wards.

Hospitals such as UCLH in London use these bloodthirsty worms to drain excess blood after microsurgery, which helps to promote natural healing.

They can be used in postoperative care of skin grafts, or after lost fingers and ears have been reattached.

They produce a protein that stops blood clotting - and this gives tiny veins time to knit themselves back together.

Wales is now the centre for leech therapy and home to a farm supplying tens of thousands of medicinal leeches to hospitals around the world.

Willow

Crack willow tree

Both the Ancient Egyptians and Hipocrates recommended using the bark of a willow tree for pain relief.

Its effectiveness was eventually proven in a study by the Royal Society in 1763.

But it was not until 1915 that drugs giant Bayer started selling it over the counter as aspirin.

It is now the subject of between 700 and 1,000 clinical studies each year.

And recent advances have shown it is far more than just a painkiller.

From reducing the risk of strokes to indications it could help prevent cancer, aspirin is the traditional remedy that keeps on giving.

Snowdrops

Galantamine, derived from snowdrops and now used to treat Alzheimer's disease, was first investigated by the Soviet Union, - but folk law tells of Bulgarians rubbing the flowers on their forehead to cure headaches.

Prof Heinrich says: "They were almost certainly used in traditional medicine before the Soviet's started investigating in the 50s.

"Why would you go into your garden and investigate your snowdrops?

"There must have been a reason for them to look at snowdrops in the first place"

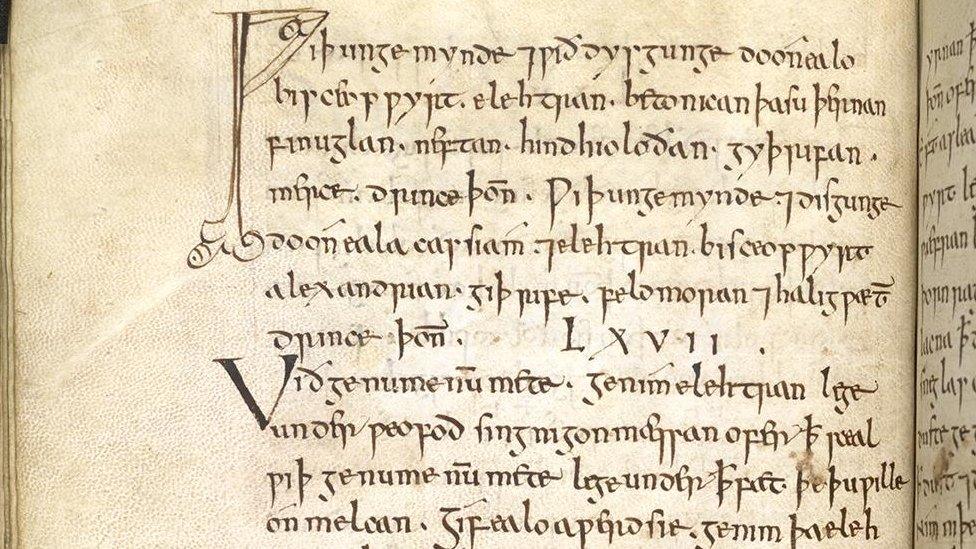

'Cow's Stomach Juice'

Bald's Leechbook

A recipe for "eye salve" from 1,000-year-old Anglo-Saxon medical textbook Bald's Leechbook states onion, garlic, wine and cow's bile should be crushed together and left in a bronze vessel for nine days and nights.

Now, tests have shown the eye salve kills MRSA in the lab faster than the best antibiotic.

"Anglo-Saxon remedies don't have the best reputation, but the idea that Anglo-Saxon medicine is superstition has clouded our judgment," says Dr Christina Lee, associate professor in Viking studies at Nottingham University, who translated the recipe.

"We need to get rid of the whiff of homeopathy and give old remedies the credit they deserve."

- Published6 October 2015