How to build a whole new face

- Published

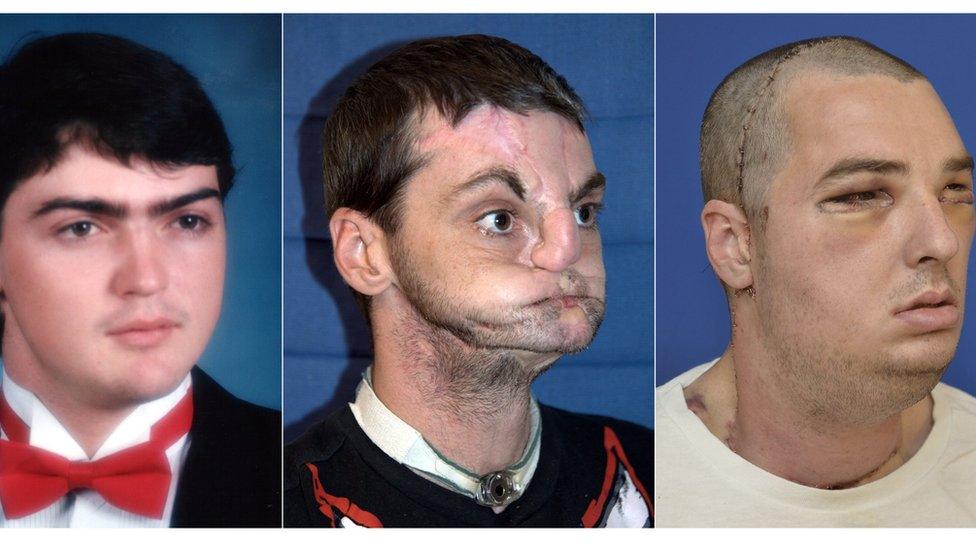

Patrick Hardison was left with major facial scarring and disfigurement from his injuries and had to wear prosthetic ears

Volunteer fireman Patrick Hardison was badly burned in a house fire as he attempted to rescue a woman he believed was trapped in the blaze.

His facial injuries from the third-degree burns were severe. He lost his ears, his eyebrows and all the hair on his head and, visually, was unrecognisable from the man he once was.

Friends put him in touch with a pioneering surgeon, Dr Eduardo Rodriguez, who is renowned for his work on face transplantation.

In August, they made history together - achieving the world's most complete face transplant to date.

Mr Hardison's new face in the first few weeks after the transplant surgery

The results, although still early and ever-changing as Mr Hardison continues to heal, are spectacular.

But behind the success are decades of experimentation, bravery and hard work.

Rebuilding a face

Since the world's first face transplant was carried out in 2005 - on a French woman called Isabelle Dinoire who had sustained facial injures after being mauled by a dog - the experience and technical capabilities in this field of surgery have progressed substantially.

Isabelle Dinoire made history in 2005 when she became the first person to receive a face transplant

Ms Dinoire had her nose, lips and chin removed and replaced with donor tissue, including skin, underlying muscles, arteries and nerves, in a 15-hour operation.

The operation was a first, but the surgical techniques had been used for a long time.

During World War Two, hundreds of airmen suffered horrendous burns and some became members of the "guinea pig club" for facial plastic surgery. Surgeons experimented, transferring the patients' own skin from different parts of the body to rebuild their faces.

But it wasn't until strong anti-rejection drugs became available decades later that doctors could start thinking about using donor tissue from the deceased to repair damaged faces.

Full face swap

In 2010, Spanish surgeons carried out the world's first full face transplant. This surgery lifted the entire face, including jaw, nose, cheekbones, muscles, teeth and eyelids on a man called Oscar.

Oscar, the world's first full face transplant patient

Two years later, Dr Rodriguez went a step further and attempted a 36-hour-long operation to repair the face of Richard Norris, a man from Virginia in the US, who had been injured in a shotgun incident.

Mr Norris had lost almost all of the middle of his face and needed a new nose, lips, both jaws and a bit of tongue.

Richard Norris before (left) and after the accident (middle), and again after the face transplant (right)

The transplant also involved all facial soft tissue from the scalp to the neck, including the underlying muscles to enable facial expression, and sensory and motor nerves to restore feeling and function.

Dr Rodriguez said at the time: "Our goal is to restore function as well as have aesthetically pleasing results."

And restore function they did. Mr Norris regained his speech and skin sensation as well as better motor control of his face muscles.

Buoyed by the success, Dr Rodriguez looked for other patients whom he might be able to help, and when he met Mr Hardison, decided to try an even bigger face transplant procedure - the most extensive yet.

Dr Rodriguez specialises in microsurgery and plastic surgery, restoring function as well as getting good cosmetic results

The donated tissue included the entire scalp, forehead, face, eyelids and ears, as well as some of the underlying muscles, nerves and blood vessels.

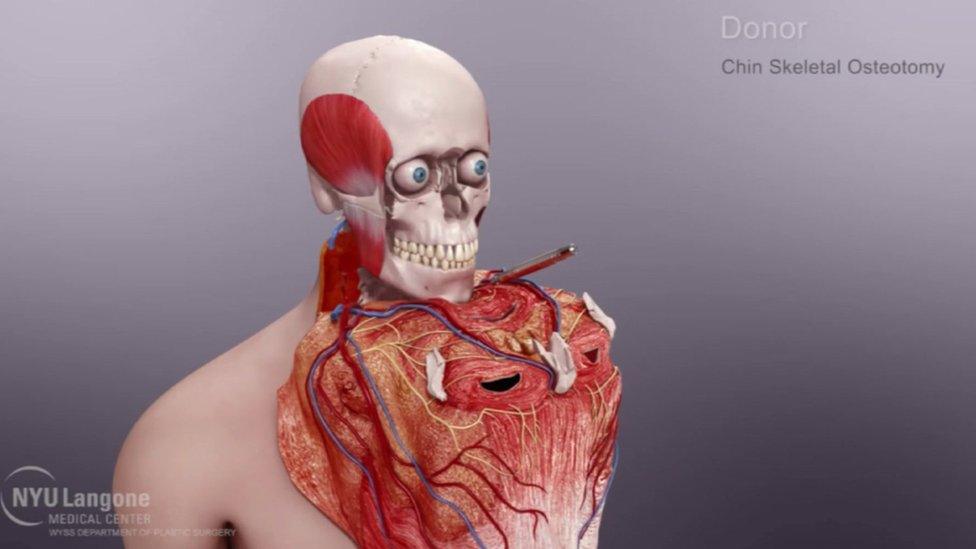

Crucially, Dr Rodriguez also transplanted key pieces of the facial skeleton - the bridge of the nose, the tip of the chin and parts of the cheekbones. This meant that the facial features would have a better scaffold to hold on to and they could be slotted into the correct anatomical place.

Soft tissue and bone fragments were removed from the donor

The upper and lower eyelids were draped on to the patient, and inner linings of the nose and mouth stitched into place.

The result - a hybrid of Mr Hardison and his donor, a young man called David Rodebaugh who had been fatally injured in a cycling accident.

Within the final hours of surgery, signs of success were evident.

Mr Hardison's new face, particularly his new lips and ears, had a good colour, indicating that the blood supply had been restored. The hair on his scalp, as well as the beard on his face, began growing back immediately. He was able to use his new eyelids and blink on the third day of recovery, after the swelling began to subside. He was sitting up in a chair within a week.

And now, three months on from the surgery, he is living an independent life.

Like all transplant patients, Mr Hardison will need to remain on anti-rejection medication for the rest of his life to stop his body's immune system from fighting his new face.

And he will have regular check-ups with Dr Rodriguez and the face transplant team at the NYU Langone Medical Centre where the groundbreaking surgery took place.

In a few months, once all the swelling has subsided, the surgeons plan to do another operation to remove some of the excess skin around Mr Hardison's eyes and mouth.

Then Dr Rodriguez will be looking for the next patient he might be able to help with a new face.

- Published16 November 2015

- Published17 November 2015