Junior doctors row: Lessons learned from 1975 strike

- Published

Junior doctors are on the cusp of downing their stethoscopes and scalpels and walking out of wards and clinics to take part in a wave of strikes across England on Tuesday.

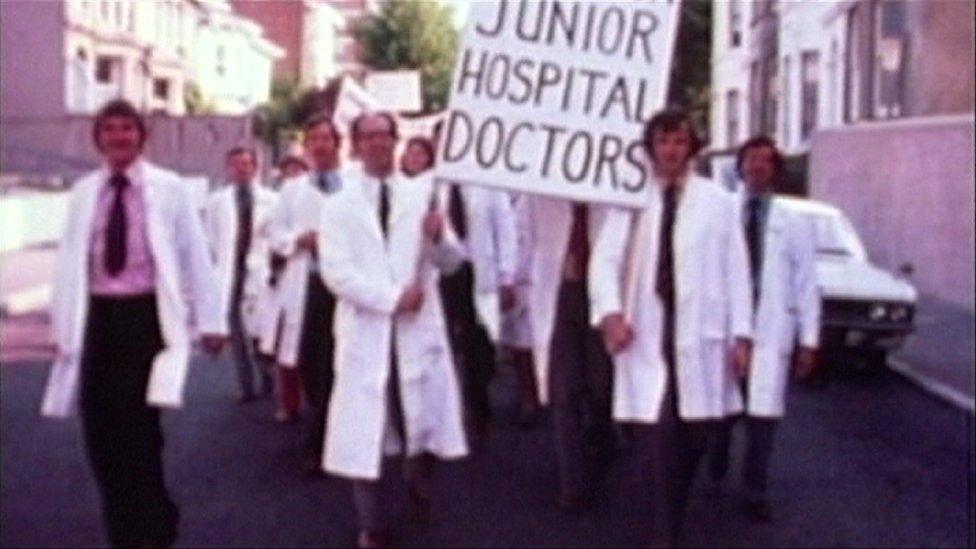

Industrial action by this group is relatively rare. But it has happened before - the last major strike over pay and conditions by juniors was in 1975.

Some of the reasons behind the strikes are similar - dissatisfaction over pay and many medics feeling undervalued and overworked.

But what would the doctors of 1975 say to their colleagues today? Did the strike work? And is there anything today's juniors can learn from their colleagues?

Steve Iliffe, now a retired professor of elderly care, had only just qualified as a doctor when the first strikes began.

In 1975, this nurse said a consultant was doing the job of four doctors

He worked as a house officer at Leicester Royal Infirmary and remembers the hours being "long and horrendous".

While an 80-120 hour week was standard, the longest shift he endured was 132 hours.

Apart from the hours, one of the other major issues at that time was that the rate of pay fell sharply after the first 44 hours were done - reducing by about two-thirds.

Though the standard working hours have decreased for many doctors, preventing juniors working excessive hours and the pay they receive for working anti-social hours are central to both conflicts.

But crucially in 1975 the whole atmosphere across the country was different, Prof Iliffe says.

The strike emerged against a background of frequent protests and picketing by, among others, nurses, hospital engineers, lab technicians, miners and ambulance crew.

The juniors found lots of other people around them - including paramedics, porters and of course patients, all involved in disputes of their own.

This may have made it more generally acceptable and easier to strike, with lots of ancillary staff supporting picket lines.

Action spread across the country and lasted several months - with doctors advised to stick to a 40-hour week.

But according to Prof Iliffe, who was a member of the Medical Practitioners' Union, strikes faded away as time went on.

He says doctors did win some concessions on pay but the hours didn't really change and many were left feeling deflated after all their efforts.

Prof Iliffe says: "What I learnt from 1975 is that we weren't clear at the beginning about what the end objective was.

"There wasn't a clear aim beyond a strong feeling that things weren't right.

"And my concern now is that they don't exactly know what they want either."

Meanwhile, Dr John Bache, a retired accident and emergency doctor and a houseman at the time of the strike, chose not to take action.

He remembers driving through the picket lines at the entrance of the hospital.

He said: "It was not a popular thing to do but I felt strongly that it was wrong to strike. And I still do.

"Striking puts the most vulnerable people - sick patients - at risk."

Technically challenging

He feels it is probably harder to go against the grain today and not support fellow colleagues who want to strike.

Unlike 1975, social media has become a powerful force with many juniors expressing their views and some may feel pressure from these forums too.

Despite this, Dr Bache says he has a huge amount of sympathy for the doctors on the front line today.

"I'm sure what is going through their heads right now is the same as in 1975. They don't want to hurt their patients."

He says in many ways the work now is more technically challenging and the hours often more intense - with fewer colleagues to turn to for support.

Dr Bache remembers working a 100-hour week but the difference between 1975 and the rotas of today, he says, was that doctors weren't necessarily working every minute of their shifts.

There were moments to rest in the doctors' residence - and even catering staff to make you bacon and eggs once in a while.

Now, Dr Bache says, the 13-hour shifts are often relentless.

There were some reports that ambulances had to be diverted and lives were put in danger

According to Dr Bache, what was different then was the public were very strongly behind the juniors - partly because many of them were striking too.

And back in those days you didn't question a doctor that much - those days are rightly over, he adds.

But he says: "What worries me at the moment is that something might go wrong and it would turn the public against the strike."

What is clear from both 1975 and the dispute of 2016 is that the cause has fired up thousands of medical staff who have never taken industrial action before.

It has brought them together as a powerful lobby group - both on picket lines and online.

And this won't be the last we hear of them.

- Published30 May 2012

- Published6 April 2016

- Published4 January 2016

- Published4 January 2016