The promise of gene editing

- Published

Sohana and her mum Sharmila

Sharmila Nikapota, the mother of a child with a rare genetic disorder, has high hopes for gene editing.

"For us this technology holds the unimaginable dream of a cure," she says.

Her 13-year-old daughter Sohana has spent her entire life covered in painful blisters, the result of a condition called recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

It is caused by two faulty collagen VII genes, which means her body does not produce the protein that helps anchor the skin in place.

I first met Sohana a couple of years ago. At the time she was having experimental cell therapy at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) in London.

Fergus Walsh explains how gene editing works

That gave some temporary relief, but the greatest long-term hope may come from gene editing.

Techniques to edit human DNA have been around for some time. For the past 15 years there has been a gene therapy unit at the Institute of Child Health (ICH) in London.

Gene therapy involves using a disabled virus - known as a viral vector - to deliver a synthetic functioning copy of a gene into cells. There is no way for scientists to know where the gene will end up amidst the billions of letters of DNA code in the nucleus of our cells.

A gene therapy trial for adults with Sohana's condition is about to get underway at GOSH.

But the collagen VII gene is so big, it is difficult to find a viral vector stable enough to deliver its payload.

Gene editing offers something far more precise - adding a gene in an exact location. Unlike gene therapy, it can also be used to snip out a faulty section of DNA.

Gene editing to transform the way we battle disease

Explaining the science of genetic engineering is not easy, but Waseem Qasim, Prof of Cell and Gene Therapy at ICH has this nice analogy: "With gene therapy, it's rather like repairing a car with no lights by strapping a headlamp onto the roof, which would need to be switched on at all times.

"With gene editing you can change the bulb in the headlamps and the lights can be switched on and off as normal - a complete repair."

There is a huge amount of excitement among biologists at the potential for gene editing.

Only last month Prof Qasim was part of a team from GOSH and ICH who announced they had rebuilt a child's immune system using gene editing.

One-year-old Layla Richards had an aggressive form of leukaemia, which had not responded to any other treatment.

Prof Qasim says all the teams working on treatments for single gene inherited disorders are now using gene editing.

Most clinical trials are at least five years away but there is great potential.

"The gene editing technologies that are coming through could potentially be a game changer for those conditions because we can now, for the first time, go in and correct specific gene changes that we weren't able to do before," he says.

The conditions likely to benefit first are those affecting the blood, immune system or muscle, where cells could be removed, re-engineered in the laboratory, and then put back.

For RDEB, it would mean gene editing Sohana's skin cells and then injecting them back in the hope that the healthy tissue would take over from the faulty.

Her mother Sharmila knows the research is still at the laboratory stage, but is understandably anxious that it should accelerate.

Many patients with Sohana's condition go on to develop skin cancers.

"The potential for cures - for miracles - really is there. The question is how long is it going to take."

Sohana and her mother Sharmila talk about EB

Crispr-Cas9

There are several types of gene editing, but the technology really took off three years ago. Profs Jennifer Doudna of University of California, Berkeley and Emmanuelle Charpentier, now at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research in Germany, discovered a cheap and efficient new system for editing DNA.

Known as Crispr-Cas9 it has been adopted by scientists around the world.

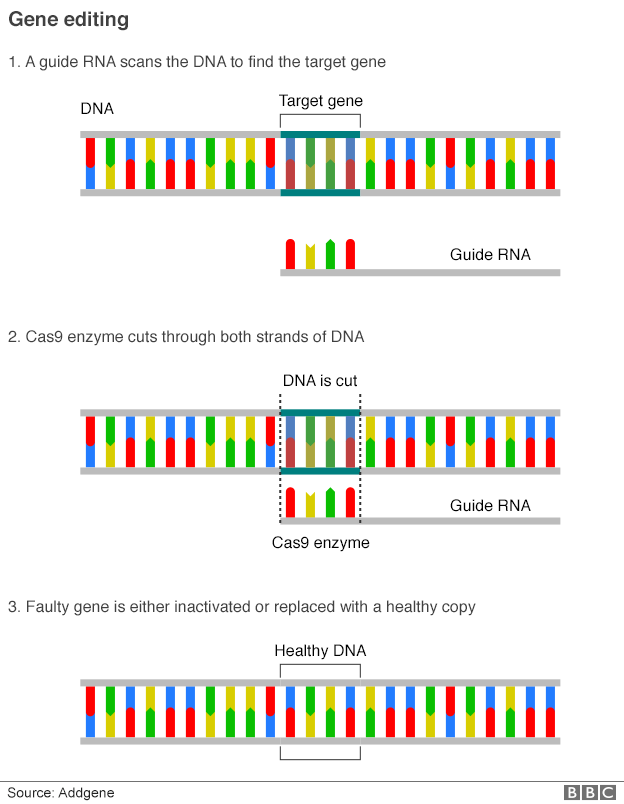

Crisprs (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) are sections of DNA, while Cas9 (Crispr-associated protein 9) is an enzyme.

They are found in bacteria, which use them to disable attacks from viruses.

Rather like a sat nav Crispr scans the genome looking for the right location and then uses the Cas9 protein as molecular scissors to snip through the DNA.

Doudna and Charpentier realised this bacterial cut-and-paste system could be used to edit human genes.

Almost immediately Crispr became the gene editing technique of choice because of its speed, accuracy and simplicity.

It has caused a quiet revolution in research labs across the world.

Experiments which once took months can now be done in weeks. And its potential is vast.

Last month scientists said they had used it to create a mosquito that can resist malaria.

Plant breeders are using Crispr to create disease-resistant strains of crops.

In April, researchers in China edited human embryos to try to correct a faulty gene that caused an inherited blood disorder, external.

The embryos used were never destined to be implanted, but the research rang alarm bells about the implications of gene editing.

Hundreds of scientists and bioethicists have gathered in Washington for an international summit on human gene editing.

Jointly organised by the National Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society of London and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the three day meeting will examine the potential of gene editing as well as its risks.

I spoke to Prof Doudna, one of the co-inventors of the Crispr system, and she said: "The implications of gene editing for medicine are pretty profound. It is already enabling scientists to create better animal models of disease. In future, we hope it could be used not just to understand disease but to cure it. If we see a mutation in a cell we can fix it. That's very exciting."

Editing DNA outside the body, as was done with Layla Richards, is unlikely to be controversial.

But altering the genes of an embryo, even purely for research purposes, is a step too far for some, even though it might eventually yield cures for inherited conditions.

The Washington summit should end with a mission statement about whether such basic research should proceed.

- Published29 November 2013

- Published10 September 2015