Gene editing: Is era of designer humans getting closer?

- Published

An international meeting of leading scientists has said it would be "irresponsible" to allow the creation of genetically altered humans.

But they said basic research involving embryo gene editing should continue in order to improve understanding of human biology.

As scientific knowledge advances and societal views evolve, they added, the clinical use of genetically modified embryos should be revisited on a "regular basis".

The gene editing summit in Washington was organised to discuss new techniques which enable researchers to alter human DNA.

Genetic enhancement has been a favourite theme for science fiction writers. The film Gattaca imagined a world where children were conceived through gene manipulation.

A Brave New World of designer humans - although still a long way off - has moved a step closer as a result new gene editing techniques.

Three years ago scientists invented a new simple cut-and-paste system, called CRISPR-Cas9, for editing DNA.

Scientists across the world immediately adopted this rapid, cheap and accessible tool in order to speed up their research.

For patients with blood, immune, muscle or skin disorders it offers the hope that their faulty cells could be removed, tweaked in the lab and then re-implanted.

Fergus Walsh reports on the science that could create designer human beings

'Blood disorder'

But even if patients carrying a genetic disease were successfully treated, they would still be at risk of passing on that faulty DNA to their children.

That's where gene editing in embryos comes in.

Fix the error in a newly fertilised embryo and - in theory - it would provide a permanent genetic fix that would pass down the generations.

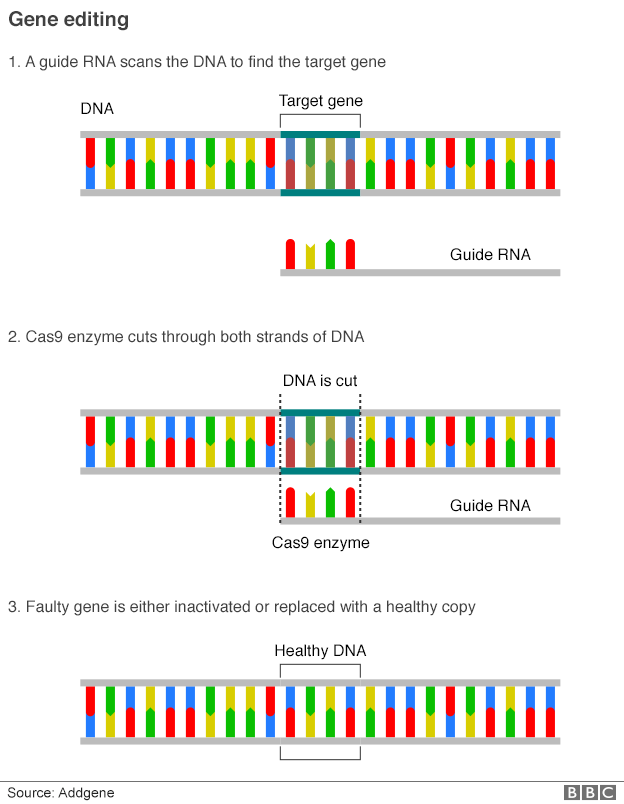

Fergus Walsh explains how gene editing works

Earlier this year, in a world-first, scientists in China announced that they had carried out gene editing in human embryos, external.

They were attempting to correct a gene that causes an inherited blood disorder, beta thalassemia.

The laboratory experiments had very mixed results, showing this technology is still in its infancy.

It was a key reason why leading science bodies decided to organise the first global summit on gene editing.

'Glimmer of light'

Not for the first time, ethics is playing catch-up with science.

For some patients, gene editing is a technology which should be embraced.

Charles Sabine carries the gene for Huntingdon's disease, an incurable brain disorder. The devastating condition affects cognition, movement and personality.

Charles Sabine (left) spoke to Fergus Walsh about the impact of Huntington's Disease on his family

His father died of the condition, while his brother John now needs round-the-clock care. Those affected have a 50:50 chance of passing it on to their children.

Charles and his wife used embryo screening to ensure that neither of their two children was affected.

But gene editing would offer the chance of correcting the fault in affected embryos.

He told me: "It's too late for me but this technology offers a glimmer of light for families suffering from genetic diseases. For generations to come this could be priceless."

Charles Sabine with his brother John who needs 24-hour care

At the gene editing summit in Washington, there has been heated discussion about whether this embryo editing should ever go from the lab to the clinic.

Marcy Darnovsky, executive director, Center for Genetics and Society in California, is not opposed to basic research using gene-edited embryos although she stresses there would still need to be strict controls.

But she would like to see international agreements banning the technology from ever being used for reproduction.

"It's too risky and we don't need it. We already have embryo screening, which in the vast majority of cases allows affected parents to have a healthy child," she said.

"This opens the door to a world of genetic haves and have-nots. We don't need more discrimination."

But Prof George Church, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School, believes it can and should be allowed.

"People instinctively had fears about IVF technology at the beginning. This is the same. We need to do the research and once we get through safety and efficacy testing then it can progress to clinical trials," he said.

But talk of designer humans and genetically engineered children is all premature.

None of the scientists at the Washington summit is remotely ready to take embryo gene editing into the clinic.

It also risks overshadowing what might be a key benefit of embryo gene editing research, namely the increased understanding of human biology.

A team at the Francis Crick Institute in London has already applied to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, for a licence to do embryo gene editing.

Sir Paul Nurse, director of the Crick, says the research may ultimately lead to improved efficiency of IVF and new treatments to reduce the rate of miscarriages.

He said: "This will really advance our ability to do research in human cells to understand how they work in health and disease - so it will be hugely significant."

He also wants a public debate about the potential for gene editing to cure genetic conditions, which he believes might come in the next decade.

"If it's the case, we need to be well prepared for it and that means a proper engagement between the public, scientists and Parliament.

"The good news is that we are the best nation for discussing these issues that I've come across - but the debate must start now."

- Published10 September 2015

- Published2 December 2015

- Published1 December 2015

- Published1 December 2015