Winter in the NHS: The lost beds problem

- Published

Walk into any hospital and you will see wards full to bursting. An empty bed is a rarity - certainly for any length of time.

And with winter here, it's only going to get worse. But arguably the biggest problem the NHS is facing this winter is not the sheer numbers - it's the fact that many of those people don't actually need to be there.

Each month thousands of beds are being taken up by people who are fit to be discharged, but can't be. In some places one in five beds is occupied because of this.

Why? Because the support is not in place to allow them to leave.

Vulnerable patients, particularly the elderly, may need carers or nurses available to look after them at home, or equipment such as grab rails and stairlifts to be installed. Others may require a place at a care home to be arranged.

Until any of this happens, they have to stay in hospital. In NHS-speak, this is known as a delayed discharge.

Winter is a particularly busy time for A&E units, as Nick Triggle reports.

And, as an issue, it's getting worse. In England the number of delays - measured as "bed-days lost" - has hit record levels after they increased by more than 30% in the past five years to 160,000 a month when you count all settings including hospitals, mental health facilities and smaller community hospitals.

But this is not just a problem in England. In Wales, numbers started creeping up at the start of January last year.

For some patients the delays last just a few days. But for others it can be weeks. Astonishingly in Wales in September there were two patients who had been stuck on hospital wards for over six months.

Knock-on effect

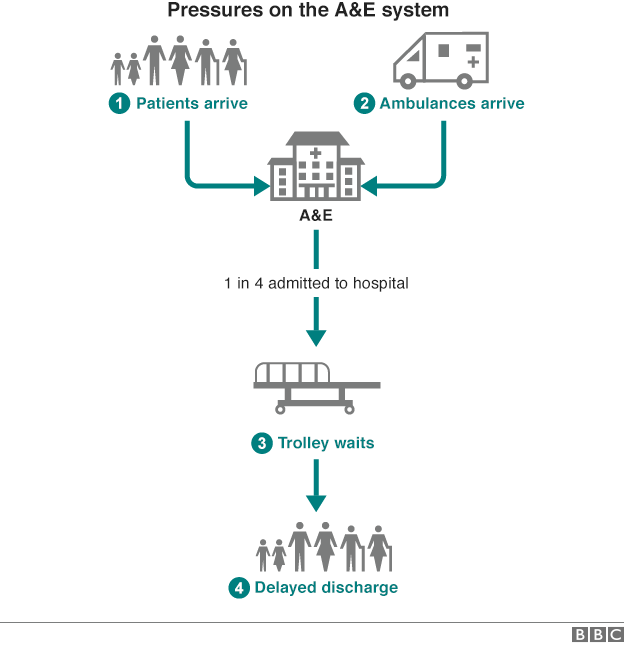

This, of course, is not good for patients. But it's also bad for the NHS. When a patient is delayed it has a knock-on effect by increasing waits in A&E as staff can't find beds for their patients.

This in turn has an effect on ambulances. Paramedics need A&E staff to be available so they can hand over patients. If they are busy trying to find beds for patients already inside the hospital, crews have to wait. Hence, we see queues of ambulances forming outside A&E units during really busy times. In a nutshell, the system grinds to a halt.

This is why respected figures ranging from John Appleby, the chief economist at the King's Fund think tank, to Lord Kerslake, the former senior civil servant who now chairs King's College Hospital in London, have spoken recently about the growing crisis of delayed discharges.

So what is the solution? Many point to increasing investment in social care. About a third of the delays are related to a lack of care services being available. But, of course, a number of these happen because families have to arrange for a care home place to be found. Something which, with the best will in the world, cannot be hurried.

The NHS in winter: Want to know more?

Special report page: For the latest news, analysis and video

Winter across the UK: A guide to how the NHS is coping

Video: Why hospitals are under so much pressure

Video: How a hospital can grind to a halt

So instead attention is turning to Scotland. Like the rest of the UK, it experienced a difficult winter last year.

But this year it's in a much healthier position. In fact, going into winter, it's the only part of the UK where A&E waiting times are actually better than they were 12 months ago.

The reason? Well, it has certainly helped that hospitals have been able to get patients out: the number of delayed discharges has fallen by 8%.

Experts believe a major factor behind this is the way many areas have started investing in intermediate care beds. These are beds set aside, mainly by care homes, for hospitals to discharge patients into. Once there, they can then be assessed and the necessary care arranged.

In Glasgow, about 100 beds have been opened for this purpose in the past year. The impact has been staggering. On the first Monday of December last year 117 hospital patients had been waiting more than 72 hours to be discharged. The first Monday of this month the figure was 27.

- Published25 November 2015

- Published26 November 2015

- Published22 October 2015