Are we fighting cancer the right way?

- Published

A huge amount of effort and money is spent fighting cancer globally. But are we getting that fight right?

With the number of new cancer cases set to hit 24m by 2035, do we need to rethink our approach?

Four experts talk to the BBC World Service Inquiry programme.

Dr Vincent DeVita: Regulation stifles innovation

Dr Vincent DeVita is one of the leading cancer specialists in the USA, and helped develop a cure for Hodgkin's disease in the 1960s.

"The process we're going through now stifles innovation. We're doing a lot of things right. We're in the middle of a molecular revolution, but we're not taking advantage of all the information that we have because of the regulatory apparatus.

"A few years ago a study looked at how long it took an idea to [become a cancer treatment] protocol, be approved and initiated. The average was 800 days, in some cases 1,000.

"And if you made a change in the protocol, you had to start all over again. In some cases, 29 signatures were required to approve a protocol.

"The programme which ultimately cured Hodgkin's disease took us three years. It would take us 15 years to do it now.

"Cancer cells are wily. If you just attack them with one drug, they quickly learn how to get around it. The idea of combination chemotherapy is to hit them in three or four different areas at the same time. We have proof that you require combinations of some sort for the great majority of cancers.

"A lot of innovation occurs in what we call the 'post-marketing period' for drugs. The drug gets approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and then doctors can mix and match and do studies. Nowadays that is very tightly regulated.

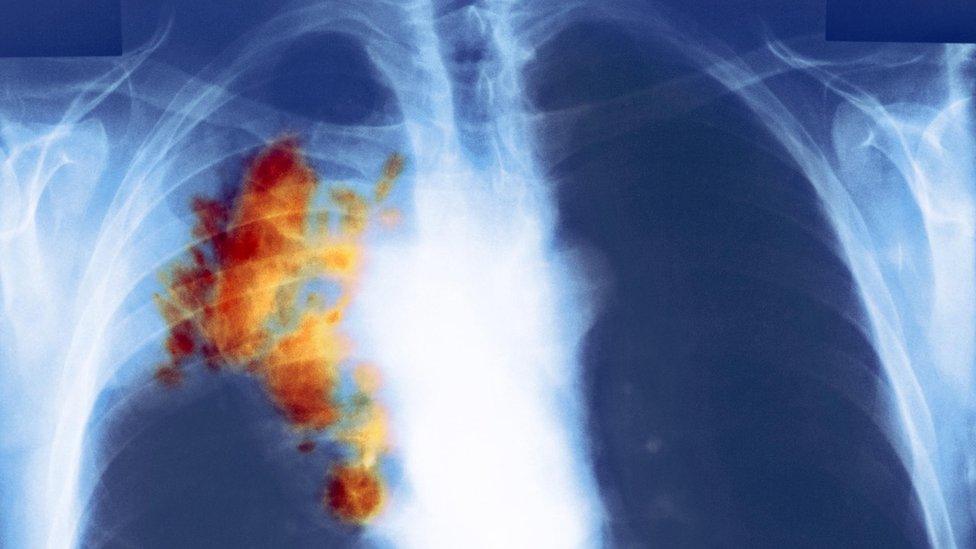

Lung cancer patients could benefit from drugs approved to tackle other types of tumours

"I lost my sister in May from lung cancer. A drug that is now working very well on lung cancer was available in her hospital. It had already been approved by the FDA for melanoma, so we knew it was safe but they had not yet approved it for lung cancer so she couldn't get it even though it was the best drug available.

"She missed an opportunity to have maybe a 60% chance of a good prolongation of her life. That's happening all over the country - drugs are being tested in ways that are unnecessary, delaying access to patients who can benefit from them.

"It's all very-intentioned. It's done in the name of the protection of patients, but I think we let the pendulum swing a little bit too far in the other direction."

Heidi Williams: Incentives can distort available treatments

Heidi Williams is an assistant economics professor at MIT.

"If you look at drugs that get approved by the FDA, they all tend to be for very late stage cancer patients - patients that are very close to the end of their life, who live one month longer than they would have. It's very rare that we see drugs approved to treat early stage cancers or to prevent cancer.

"There were about 12,000 clinical trials to treat late stage cancer patients, relative to about 6,000 for healthier cancer patients and about 500 for cancer prevention.

What should the relationship be between private and state-funded clinical trials?

"For cancer 'effective' usually means evidence that your drug improves survival relative to a control group. For patients with very advanced cancers you only need a relatively short clinical trial in order to document evidence that people in your treatment group live longer.

"For patients with, say, localised breast cancer who are relatively healthier, you would need a much longer clinical trial in order to show evidence that your drug reduces mortality rates.

"That difference in clinical trial lengths matters because longer trials are more expensive and take more time.

"Also pharmaceutical firms almost always file for patent protection before starting clinical trials, [so] drugs that require longer clinical trials receive shorter effective patent terms, because more of the term is eaten up during clinical trials.

"The conclusion we come to is that incentives seem to matter. We might want to think about more public funding on early stage cancers or on cancer prevention, relative to public funding on later stage cancers, where the private sector is more likely to come in and provide that research investment.

"We estimate that trying to address this distortion between private incentives and social incentives could have a really important impact on patient survival."

Dr Christopher Wild: Prevention is vital

Dr Christopher Wild is director of the International Agency for Research on Cancer, the specialist cancer agency of the World Health Organisation.

"At the moment, perhaps 40 to 50% of cancers could be prevented - if we were able to translate the knowledge we have about what causes cancer into effective interventions and reduce exposure to those risk factors.

"It's worth adding as well that the pattern of cancer and risk factors is quite different in different parts of the world.

"Typically in the low-income countries we see quite a lot of cancers associated with chronic infections, so cervical cancer, associated with the Human papillomavirus, liver cancer associated with Hepatitis B virus and stomach cancer, which is linked to a bacterium in the gut.

"What we're seeing is the addition of cancers now which are more common in high-income industrialised countries, such as breast cancer and colorectal cancer, prostate cancer. If you look at a country's progression in relation to colorectal cancer rates, those two things go up together. It's almost as if colorectal cancer is a good index of development.

Early detection is crucial in breast cancer

"What's allocated to prevention is typically 2 to 3% of the overall budget, so it's quite low.

"It's a complex mixture of reasons. You can make money out of getting more effective treatments, and that's not so obvious with prevention, and I think one of our challenges is to demonstrate the economic value of cancer prevention.

"I think it is beginning to change, partly because there's an increasing recognition at a political level that no country can afford to treat its way out of the cancer problem.

"We've got around 14 million new cases per year at the moment, and we project forward to about 24 million new cancer cases every year by 2035, so the costs of treating those cancer patients are spiralling.

"I hope that political understanding will translate to a different approach to cancer control generally. Trying to prevent the disease in the first place is a necessary complement to the advances in treatment we're also aiming at."

Professor Pekka Puska: The Finnish experiment

Professor Pekka Puska is a former director general of the Finnish National Institution for Health and Welfare. As a young public health academic he led a landmark project to tackle heart disease in North Karelia.

"The mortality rate of heart disease among men was the highest in the world. The blood cholesterol levels were record high, due to the very high fat diet. [They ate] little fruit and vegetables, blood pressure levels were high, men smoked a lot.

"They had a big breakfast, putting an enormous amount of butter on bread, tea and coffee with cream, and then during the day the meals were potato with bread with a lot of butter. Then fatty meat prepared fried with butter. It was fairly typical that the man had a packet of butter every day.

Tackling the local community's traditional high-fat diet was key

"Changing behaviour is not easy. There is inertia. Lifestyles are related to habits, local culture, local environment and there are a whole range of commercial and financial interests.

"There is no magic bullet, [but] you can change your lifestyle, your diet, you can stop smoking. Information was the first part.

"The housewives were worried about their men, so they were powerful in persuading the men to change their diet, even if they were resistant. They started to mix non-fat milk with the fatty milk so the husbands didn't realise.

"There was a popular dish called Karelian stew, which was covered with white fat. Together we changed the recipe so it had more lean meat, less salt. They started to call it Puska's stew.

"There were anti-smoking and cholesterol-lowering competitions between villages.

"The dairy industry became worried because sales of butter started to reduce, and in the 1980s there were some big events against us with political support, so it wasn't easy.

"But when people started to see the results of cholesterol levels lowering and heart disease mortality starting to decline that reinforced the development.

"We calculated that if the cardiovascular mortality levels had stayed on the level that they were in 1972, something like a quarter of a million people below 75 would have died of cardiovascular disease.

"Because smoking among men was such a tremendous problem, the annual mortality of lung cancer, tobacco-related cancers have now declined by close to 50 per cent.

"All this led to something like a 10-year increase in life expectancy."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published1 February 2016

- Published30 January 2016

- Published18 January 2016