Sugar tax: How will it work?

- Published

A new sugar tax on the soft drinks industry will be introduced in the UK, the chancellor has announced as he unveiled his Budget.

It is something that has been talked about for some time, but has still come as a surprise.

The move has been hailed by campaigners as a significant step in the fight against child obesity.

How will they decide which drinks to target?

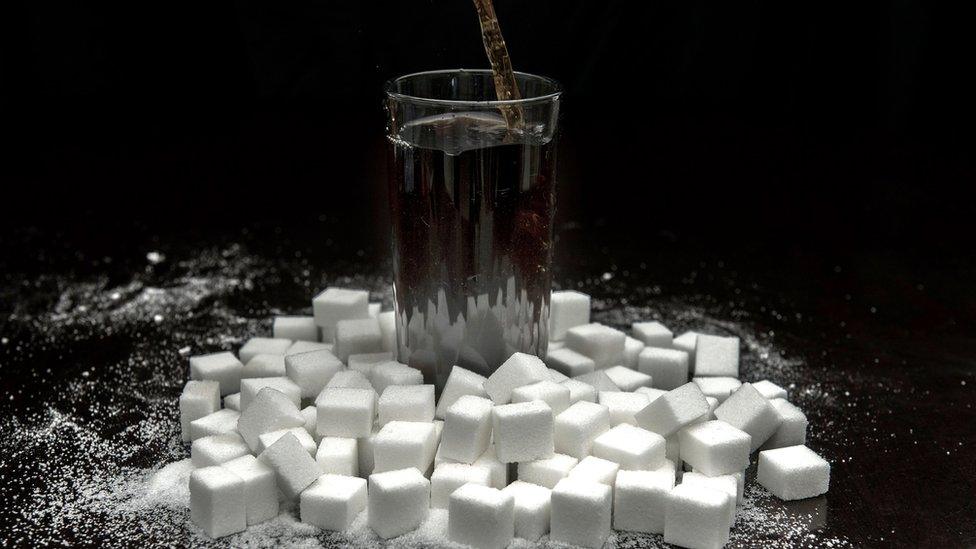

The levy is squarely aimed at high-sugar drinks, particularly fizzy drinks, which are popular among teenagers.

Pure fruit juices and milk-based drinks will be excluded and the smallest producers will have an exemption from the scheme.

It will be imposed on companies according to the volume of the sugar-sweetened drinks they produce or import.

There will be two bands - one for total sugar content above 5g per 100 millilitres and a second, higher band for the most sugary drinks with more than 8g per 100 millilitres. Analysis by the Office for Budgetary Responsibility suggests they will be levied at 18p and 24p per litre.

Examples of drinks which would currently fall under the higher rate of the sugar tax include full-strength Coca-Cola and Pepsi, Lucozade Energy and Irn-Bru, the Treasury said. The lower rate would catch drinks such as Dr Pepper, Fanta, Sprite, Schweppes Indian tonic water and alcohol-free shandy.

Who has been pressing for this?

The whole health community, more or less. In recent years campaigners have been putting forward a vociferous case for why a sugar levy is important in the fight against childhood obesity.

The most high-profile supporter has been TV chef Jamie Oliver, who has introduced a sugar levy in his restaurants. He set up an e-petition that saw more than 150,000 people backing a tax.

NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens has also spoken out in favour of a tax and has announced the health service will be introducing its own "tax" in hospitals.

Why not on chocolate?

When it comes to a sugar tax, all the emphasis has been on drinks. There are a number of reasons for this.

Firstly, unlike a chocolate bar or slice of cake, they are not automatically seen as a treat. People who drink them tend to have them every day.

Secondly, some of the drinks are incredibly high in sugar. A typical can contains enough sugar - about nine teaspoons - to take someone over their recommended sugar intake in one hit.

For teenagers they are the number one source of sugar intake while overall, children get a third of their daily sugar intake from them.

They have also been dubbed "empty calories" as they have no nutritional benefit.

What will happen to the money?

Sugar in fizzy drinks

35g

The amount of sugar in a 330ml can of Coca-Cola (7 teaspoons)

30g

The recommended max. intake of sugar per day for those aged 11+

-

£520m The amount George Osborne expects the sugar tax to raise

Mr Osborne said the money raised - an estimated £520m a year - will be spent on increasing the funding for sport in primary schools.

There has been pressure on ministers to increase spending in this area to build on the legacy of the 2012 Olympic Games and in light of the low numbers of children who take part in regular activity.

Research has shown that half of seven-year-olds do not do enough exercise.

But while the tax applies to the whole of the UK, Mr Osborne announcement on where the money is spent applies solely to England. The devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are free to decide how to spend their share.

How many children are obese?

At the start of primary school one in 10 children in England is obese (very overweight) and by the end it is one in five.

If you take into account pupils who are overweight, those figures rise to one in five and one in three respectively.

There are fears this could rise even further - although there are some signs obesity rates may be starting to level off.

The issue has been described as one of the most serious public health challenges for the 21st Century by the World Health Organization, while NHS England's Simon Stevens has dubbed it "the new smoking".

- Published19 February 2016

- Published22 October 2015

- Published18 January 2016

- Published7 January 2016

- Published25 January 2016