Malaria resistance 'unable to spread'

- Published

The first case of the malaria parasite being unable to spread its resistance to drugs has been discovered by scientists in Australia.

Tests showed the parasite can learn to shrug off the effects of the drug atovaquone, but in doing so it cripples a later part of its life cycle.

The team at the University of Melbourne hope the "genetic trap" will lead to new ways of curbing malaria.

They are aiming to perform field tests in Kenya and Zambia.

Atovaquone was introduced in 2000, but it became less popular when resistance was almost immediately detected., external

The concern with resistance is that it spreads and eventually the drug becomes unusable as it can no longer kill the malaria parasite.

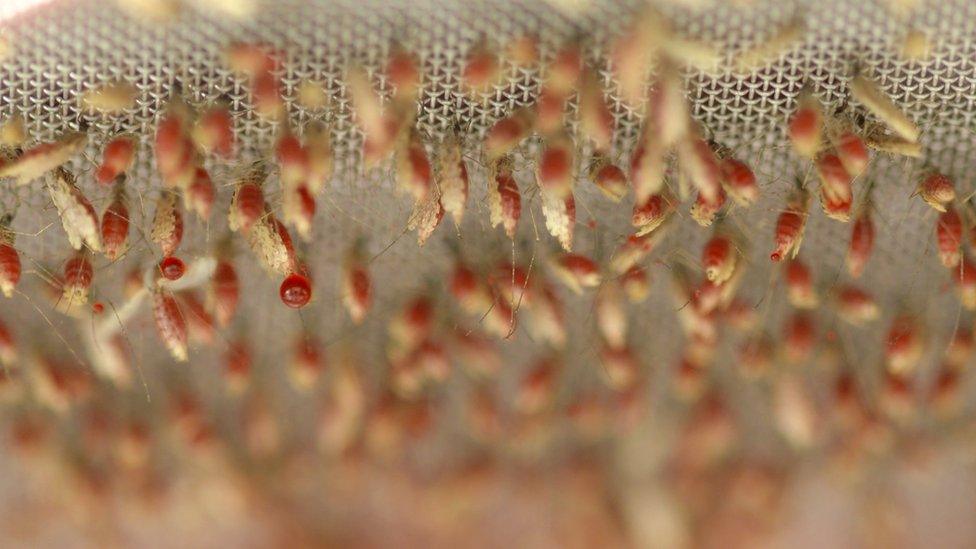

The researchers followed the full and complex life cycle of the malaria parasite in both animals and mosquitoes.

The malaria parasite infects red blood cells

In initial tests on mice, published in the journal Science,, external they confirmed what had long been known - that resistance to the drug can emerge.

However, the parasite has to change in order to become resistant and the study showed it altered the way it releases energy from food.

This helped the parasite survive the chemical onslaught in the mouse's bloodstream where there is a free and easy supply of sugar.

But it is harder for the parasite inside a mosquito and it had lost something vital for life in those more hostile conditions.

So despite resistance emerging in one host species, it was unable to survive in the other.

In 44 attempts to spread a resistant parasite from one mouse to another, involving 750 mosquito bites, it was successful only once. And that resistance was unable to spread any further.

Prof Geoff McFadden, one of the researchers, told the BBC: "I think it could be really big, it could really change the way we use this drug."

He added: "The development of drug resistance may not be a major problem if the resistance cannot spread, meaning the drug atovaquone could be more widely used in malaria control.

"We now understand the particular genetic mutation that gave rise to drug resistance in some malaria parasite populations and how it eventually kills them in the mosquito, providing new targets for the development of drugs."

Experiments with the human malarial parasite showed similar findings, but the researchers now want to test it in the field.

About half of the world's population, around 3.2 billion people, are at risk of the disease. It kills around 440,000 people each year.

Commenting on the findings, Prof David Conway from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told the BBC: "Any resistant parasites that arise in a person taking the drug cannot be transmitted to other people, so resistance should always remain very rare.

"This drug is normally used in a co-formulated tablet with an unrelated drug called proguanil to prevent and treat malaria, but it is expensive and normally only used by travellers from wealthy countries.

"Other antimalarial drugs are the mainstay for prevention and treatment throughout the world and resistance to most of these is spreading, as the parasite gene mutations involved do not prevent transmission."

Follow James on Twitter., external

- Published17 September 2015

- Published17 September 2015

- Published27 October 2015