Gene editing 'boosts' cancer-killing cells

- Published

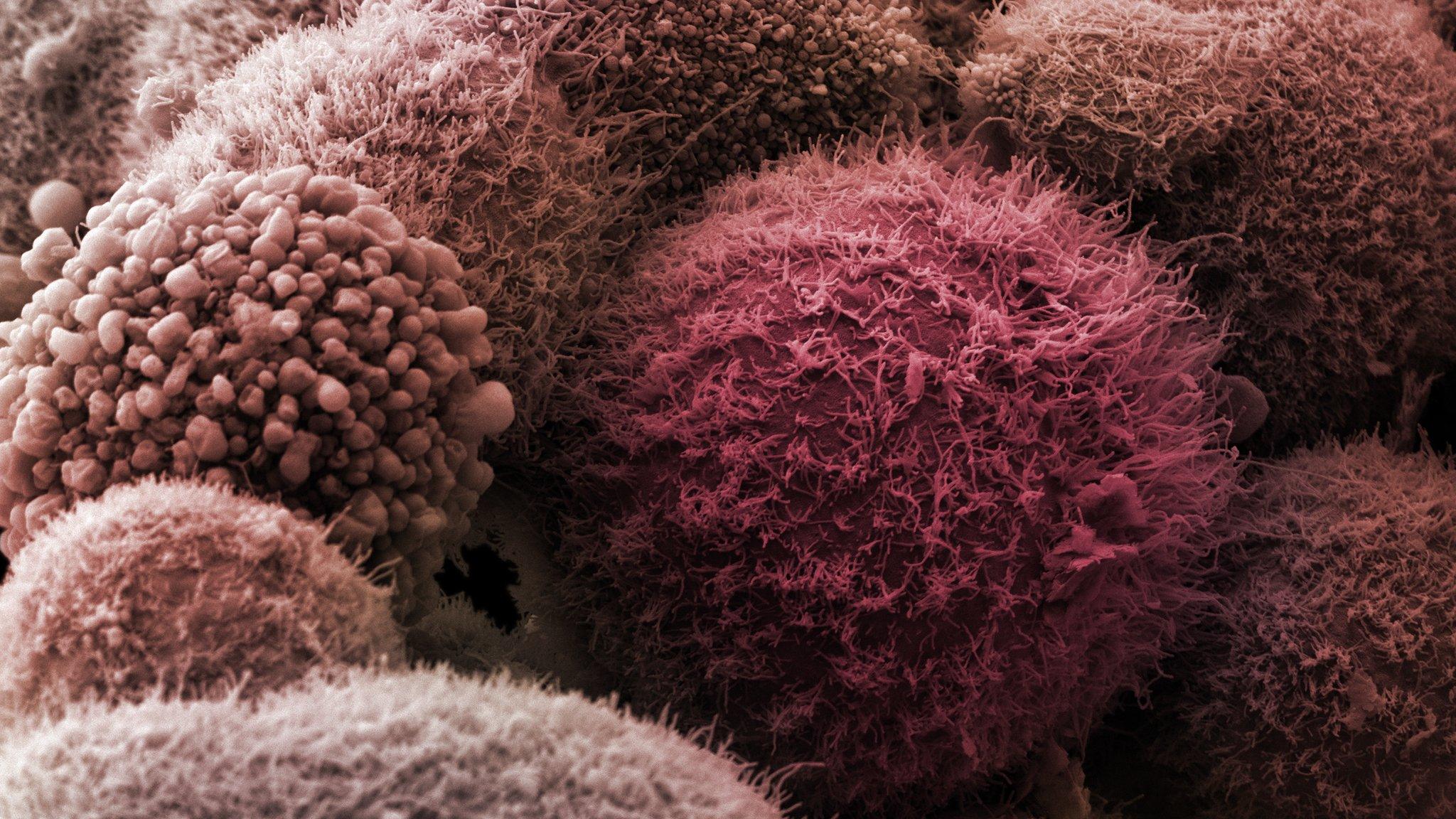

Immune cells (spheres) attacking cancerous tissue

Cancer scientists have genetically modified the immune system to help it attack tumours in mice.

The immune system is the body's own defence against infection and cancer, but tumours develop ways of stopping the onslaught.

The University College London team manipulated the DNA of immune cells to allow them to keep up the fight.

Experts said the idea needed to be tested in human trials, but it was still exciting.

Harnessing the power of the immune system to fight cancer is one of the most exciting fields in medicine.

A lot of the research is targeted at the "chemical handshake" that tumours use to disable immune cells.

A class of drugs called checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, interrupt the handshake and are already available for patients.

This has lead to spectacular results for some patients, but it can lead to side-effects as the drugs affect the whole immune system.

The approach now being tried effectively cuts off one of the hands - known technically as PD-1 - to prevent the handshake, but is targeted only at those immune cells attacking the cancer.

In experiments on mice, scientists extracted killer T cells - which gobble up cancerous tissue - from inside the tumour. The assumption is the immune cells clustering inside the tumour are trained to attack it.

Cutting edge gene editing technology was then used to change the DNA - the code of life - inside the killer T cells so that PD-1 was removed and cancers would be unable to stop them.

It is known colloquially as "cutting the brakes".

In experiments on melanoma and fibrosarcoma, mouse survival increased from less than 20% after 60 days without treatment to more than 70% with treatment.

Dr Sergio Quezada, one of the researchers, said: "This is an exciting discovery and means we may have a way to get around cancer's defences while only targeting the immune cells that recognise the cancer.

"While drugs that block PD-1 do show promise, this method only knocks out PD-1 on the T cells that can find the tumour - which could mean fewer side effects for patients."

Dr Alan Worsley, from Cancer Research UK which funded the study, said: "I think it's actually pretty exciting - it's elegant, simple, straightforward and it makes sense.

"We're going to see how this works in trials, but potentially it gets around the side effects."

He said in immunotherapy drug trials "so many people had to come off because of the side effects, here it's not your whole immune system going crazy it's just those in the tumour."

Follow James on Twitter, external.

- Published4 March 2016

- Published1 June 2015

- Published24 February 2016