'New era' of personalised cancer drugs, say doctors

- Published

Cancer is entering a "new era" of personalised medicine with drugs targeted to the specific weaknesses in each patient's tumour, say doctors.

Precision medicine is one of the big themes at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Doctors say "breath-taking" advances in the understanding of tumours are being used to unlock new treatments.

But there are also concerns that patients are not getting access to the precision medicines we already have.

The premise of precision medicine is that cancers are not all the same - even those in the same tissue - so a tailored approach is needed.

It is the same approach as in football - you modify your tactics to face Barcelona, Newcastle United or Skegness Town.

DNA clues

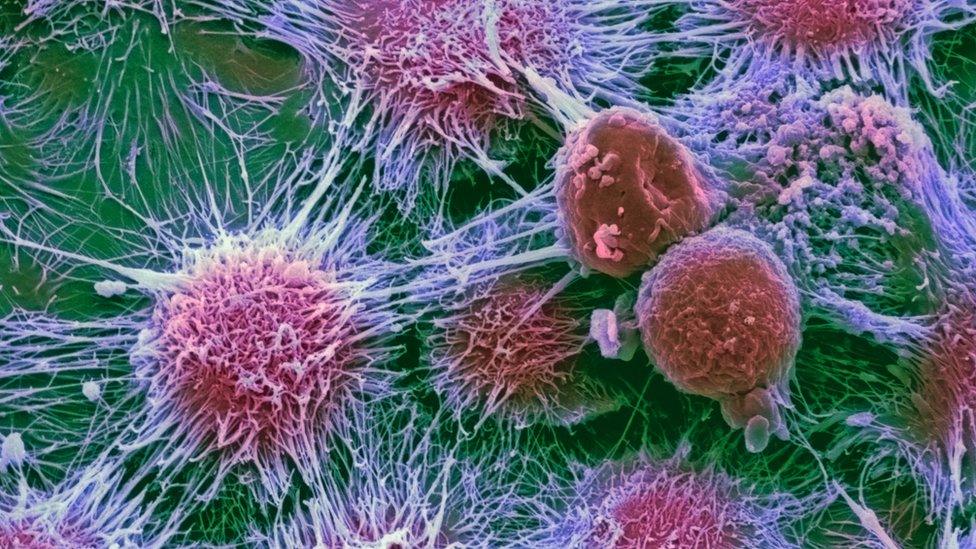

Cancers are normal cells that have become corrupted by mutations in their DNA that leads to uncontrolled growth.

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy kill everything, including healthy tissue.

The idea of precision medicine is to test every patient's tumour, find the mutations that have become essential for it to survive and then select a targeted drug to counter-act the mutation - killing the tumour.

This concept is not new. Women with breast cancer already have their tumours analysed to decide on treatment.

Tumours whose growth is fuelled by oestrogen have drugs to block the female sex hormone, while the drug Herceptin works in only the 20% of tumours that have specific mutations.

But a revolution in genetics - allowing scientists to rapidly and cheaply interrogate a cancer's corrupted DNA - is leading to huge excitement about a new generation of precision drugs.

Prof Peter Johnson, the chief clinician at the charity Cancer Research UK, argues: "The idea of taking something which is particular to cancer cells and targeting them isn't hugely new, what is new is our depth of understanding.

"I think it is a new era of understanding and it's driven by the technology changes which have allowed us to decipher the cancer cells genetic codes at a level of detail that was unimaginable 15 or 20 years ago.

"So in that sense we have a fantastic range of new opportunities for treating cancers."

Major advances

The world's largest cancer conference - a meeting of 30,000 doctors and scientists - has already heard how a precision approach is helping to beat cancer.

Dr Maria Schwaederle, from the centre for personalised cancer therapy at the University of California, San Diego, has presented data on 346 highly experimental clinical trials involving 13,203 patients.

Of the studies, 58 used a precision approach. Even though the trials were designed to test only for toxicity, they also uncovered huge benefits for patients.

Cancers shrank in 31% of cases when a drug was matched to the tumour's weaknesses compared with just 5% of the time without.

And the time before the disease worsened increased from three months to nearly six months with precision medicine.

Dr Schwaederle said the findings were "striking" and praised the "breath-taking advances in our ability to perform genomics" that was revealing the inner workings of tumours.

The UK's National Lung Matrix, external is already trying to match a new generation of targeted lung cancer drugs to the unique flaws in patient's tumours.

Meanwhile, another trial has been announced, external with the aim of testing 4,500 women's breast cancers to see which patients need chemotherapy.

Dr Robert Stein, a consultant from University College London, said: "We would expect to reduce chemotherapy within the trial population by about two thirds."

Further data on treating patients with precision medicine is due to be presented later.

Dr Daniel Hayes, who will take over as president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, told the BBC News website: "There's a lot going on, we're still in our infancy, but this is really starting to hit the fan.

"And frankly we're starting to become more precise in our precision medicine."

Missing out

Precision medicine should be hugely beneficial for patients as it also has far fewer side effects than either chemotherapy or radiotherapy which kill healthy tissue as well as the tumour.

However, there are concerns that patients are already missing out on established drugs like crizotinib in lung cancer, or dabrafenib in melanoma, that work effectively in a subset of patients.

An analysis by the charity Cancer Research UK found patients were not getting tested in order to get a precision treatment.

It said that in England alone there were 10,900 cases of bowel cancer each year, but 4,900 were not offered a test to see if a precision drug would help.

It estimates that at least 2,100 patients would have been suitable for a precision medicine that had already been developed.

And in lung cancer 1,400 missed out on drugs.

But Prof Johnson concluded: "I think we're just in the foothills of precision medicine at the moment, but we're really starting to get a grip on how treatments will work in the future."

Follow James on Twitter, external.

- Published3 June 2016

- Published27 May 2016

- Published19 May 2016