Junior doctors' row: The basics of the dispute

- Published

Ministers and junior doctors in England have spent several years locked in a dispute. But what exactly is the row about?

What caused the dispute?

It erupted over the introduction of a new contract. Ministers announced in 2012 they wanted to change the term and conditions, which were originally agreed in the 1990s.

Talks began but broke down in 2014. By the summer of 2015, Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt announced he could wait no longer as the government had committed to seven-day services in its election manifesto and said he would seek to impose a deal.

The British Medical Association responded by balloting its members and 98% voted in favour of strike action.

Talks restarted at the turn of the year at conciliation services Acas, but a deal could not be reached and so ministers announced in February they would be imposing the contract from this summer.

The terms included making part of Saturday a normal working day so it would not attract the weekend supplement it had traditionally done.

In the first four months of the year, there were six strikes, including two all-out stoppages, the first time in the history of the NHS that this has happened.

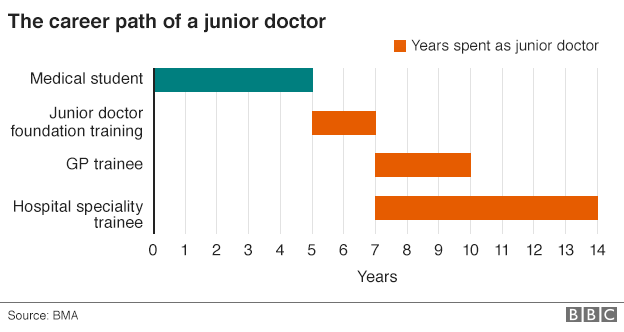

Does this just involve new doctors?

No. The term junior doctor is a little misleading. It covers medics who have just graduated from medical school through to those who have more than a decade of experience on the front line.

The starting salary for a junior doctor is currently just under £23,000 a year, but with extra payments for things such as unsociable hours, this can quite easily top £30,000.

Junior doctors at the top end of the scale can earn in excess of £70,000. But it's important to remember these doctors can be in charge of teams, making life-and-death decisions and carrying out surgery. They are behind only consultants in seniority.

In total, there are 55,000 junior doctors in England - representing a third of the medical workforce. The BMA has more than 40,000 members.

Did the two sides reach a deal?

In May, after a week-and-a-half of talks, it was announced that a deal had been reached.

There were several major changes to the contract the government said it would impose.

The rise in basic pay was reduced from 13.5% to between 10% and 11%.

In return a different system was agreed for weekend work. Instead of Saturdays and Sundays being divided up between normal and unsocial hours, a system of supplements will be paid which depend on how many weekends a doctor works.

Dr Johann Malawana, the BMA junior doctor leader who has now stepped down, welcomed it as a good deal, but agreed to put it to a vote of members. They rejected the contract by 58% to 42%.

Are weekend death rates behind it all?

This has been one of the most contentious areas of the dispute.

The health secretary has argued that he wants to improve care on Saturdays and Sundays because research shows patients are more likely to die if they are admitted at the weekend.

A study published by the British Medical Journal in September found those admitted on Saturdays had a 10% higher risk of death and on Sundays, 15% higher compared with Wednesdays.

But doctors have objected to suggestions that all those deaths are avoidable and could be prevented through increased staffing.

Patients admitted at weekends tend to be sicker and while researchers tried to take this into account they could not say whether they had accounted for it totally.

However, the paper did say the findings raised "challenging questions" about the way services were organised at weekends, while many believe it is access to senior doctors - consultants - that is key rather than junior doctors.

What about the rest of the UK?

The dispute over the contract is an England-only issue.

Scotland and Wales have both said they will be sticking to their existing contracts, while Northern Ireland has yet to make a decision.

This is largely because they do not have the pressures on costs in terms of seven-day services.

While there are moves to improve access to care at weekends elsewhere in the UK, the plans are not on the scale of what the government in England is trying to achieve.

For example, in Wales, the focus has been on more weekend access to diagnostic tests, pharmacies and therapies rather than creating more seven-day working across the whole system.

- Published22 September 2015