Eating disorders: Patients with 'wrong weight' refused care

- Published

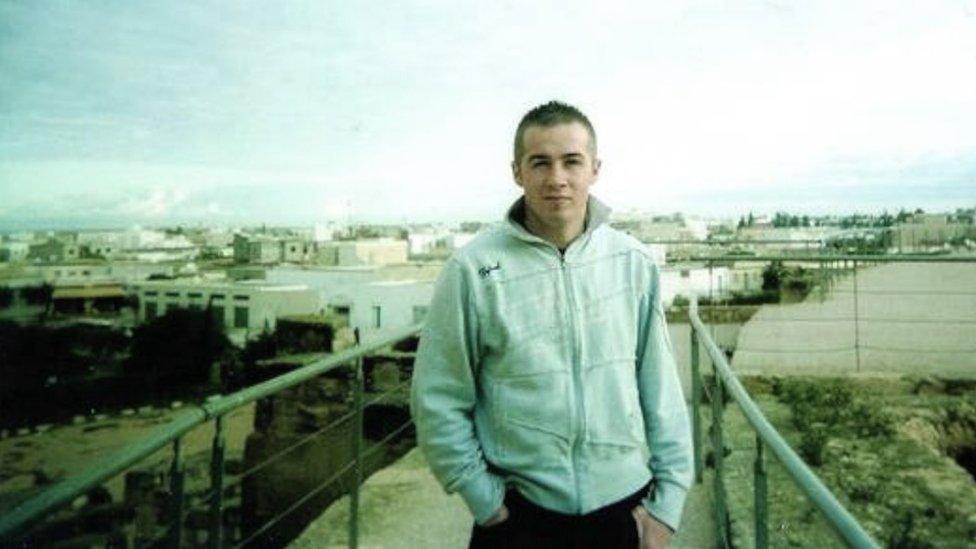

Eliza Small was told her BMI was too high for outpatient treatment

Eating disorders are complex and can affect anyone.

When Eliza Small started seriously restricting her eating two years ago, she was referred for specialist help.

Her family had a history of eating disorders. But she was refused specialist outpatient mental health treatment because her body mass index, external (BMI) was too high.

''It made me feel like I wasn't good enough at my eating disorder," she said.

"It made me feel like I would have to get better at it.''

Which she did. A family member eventually paid for her to have private treatment and she was diagnosed with atypical anorexia - all the symptoms but not the right weight.

But what is the right weight?

Prof Tim Kendall, England's most senior mental health adviser, says weight shouldn't come into it.

''If you leave an eating disorder until it's got to the point where, say with anorexia, they've lost say a third of their body weight, that has a lot of longer-term consequences which make it very difficult to treat, so it's wrong in my view to leave this until it's got very bad.

"To be told you're not thin enough - it's almost an incitement to get worse. It's like someone going to their GP and being told - you drink one bottle of whisky a day right now? Come back when you drink two.''

Prof Kendall believes patient choice is important and community care has a much better chance of success. It should never be withdrawn, he says, and hospital treatment should be enforced only in the most extreme cases.

Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) state that on its own, BMI is an unreliable measure of an eating disorder.

BBC Breakfast asked all 62 mental health trusts in England and Wales if they used BMI to decide who would qualify for outpatient eating disorder services.

Claire's BMI was too low to qualify for outpatient care

Of the 44 trusts which responded, one-third said they did.

All said they used it along with other indicators - such as the speed of weight loss. Three trusts, however, said it was a primary measure. They were Derbyshire, Coventry and Kent and Medway.

In some areas, patients might be refused access to services if their BMI was over 14. In others, like Kent and Medway, if it was over 17.5.

Some trusts said they had a minimum threshold under which people might be refused outpatient services.

This is what happened to Claire: ''The first thing they did was weigh me and tell me my BMI was too low.

"I would have to go to hospital. I didn't want to, I'd had a bad experience before and I thought I was making good progress as an outpatient. So I was left to my own devices.

"Everyone's eating-disorder experience is completely different, you can't put everybody in the same box - you have to listen to the person, to how they are feeling."

Sarah Hodge said resources were limited

Sarah Hodge, from Kent and Medway Partnership Trust eating disorder service, said they would rather not use it as a measure at all, but the problem was resources.

''You can have much more success when people have a higher BMI, they're much better able to engage with the therapy. But we just don't have the resources.''

The Department of Health says more funding is on the way: "We are investing £150m to develop community services in every area of the country for children and young people." Eating disorder guidelines from NICE are being redrafted. The hope is some of these concerns will be addressed when new guidelines are published later in the year."

Eliza said: ''You wouldn't tell someone with cancer to come back when their condition had deteriorated, why tell someone with an eating disorder?"

Eating disorders:

Research from the eating disorders charity Beat suggests more than 725,000 people in the UK are affected by an eating disorder.

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence estimates around 11% of those affected by an eating disorder are male.

The Health and Care Information Centre published figures in February 2014 showing an 8% rise in the number of inpatient hospital admissions in the 12 months to October 2013.

It is estimated that around 40% of people with an eating disorder have bulimia, 10% anorexia, and the rest other conditions, such as binge-eating disorder.

Many eating disorders develop during adolescence, but it is not at all unusual for people to develop eating disorders earlier or later in life.

Source: Beat: Beating eating disorders.

Update 4 August 2016: This story has been amended to remove the Cumbria trust from the list of trusts using BMI as a primary indicator. Although it told the BBC that BMI was a primary indicator, the trust has since stressed that it is one of a number of criteria used after a diagnosis of anorexia.

- Published17 June 2016

- Published7 April 2016

- Published9 May 2016

- Published3 June 2015

- Published11 December 2015