NHS cuts: Why they terrify people in power

- Published

- comments

NHS England's handling of the hospital cuts programme seems a fairly ham-fisted way of going about a major review of local health services.

But there are understandable reasons why bosses fell into such a secretive and controlling approach. It is known as the Richard Taylor effect.

In the late 1990s, people in Kidderminster started rallying against plans to downgrade their local hospital. It prompted Richard Taylor, a retired local doctor, to put himself forward to become an MP.

He was successful, taking the Wyre Forest seat in the 2001 election from Labour, as an independent candidate promising to fight the cuts.

His majority was 18,000, in what was the shock result of a fairly routine second election win for Tony Blair.

Since then, those at the top of the NHS and politicians have tried to tread very carefully through the minefield of health service "reconfiguration" (as they like to call it in NHS circles).

Over the years we have seen Labour ministers, such as Hazel Blears, external, Harriet Harman and Jacqui Smith, stand shoulder to shoulder with their local constituents to fight their own party's cuts.

The same happened with Tory MPs faced with changes during the coalition government.

In fact, Transport Secretary Chris Grayling spoke out against cuts that are once again back on the table.

He is MP for Epsom and Ewell in Surrey - one of the areas that could lose its hospital under plans to shake-up services in south-west London. In 2013, he described the plans as "cannibalisation".

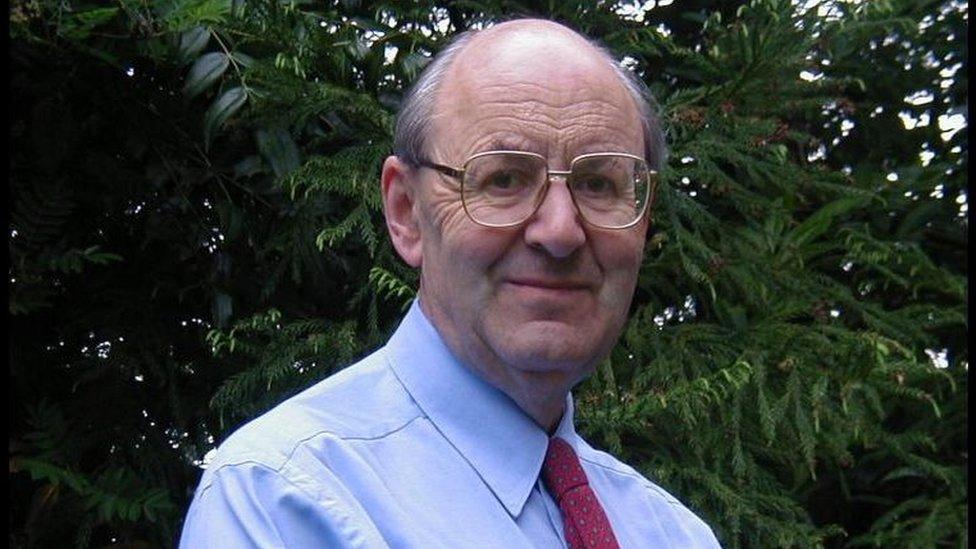

Dr Richard Taylor fought the 2001 election on saving his local hospital and ended up deposing the local Labour MP

But the opposition comes not just from MPs.

Attempts to reorganise children's heart services have seen the NHS pitted against the NHS in the courts as local hospital bosses fought diktats from the centre to close units.

The King's Fund described clear "anxieties" among ministers and the NHS leadership about the 44 reviews of local services launched this year.

In fact, that was probably diplomatic: they're terrified of how this is all going to play out.

Hence, they have resorted to rather strong-handed techniques to keep the changes under wraps - going as far as to provide advice to local managers about how to avoid answering Freedom of Information questions.

Successful change

But is this really the best way to go about it? Surely being open and transparent, engaging with staff and members of the public from the start, would be a better way?

After all, that is what happened when it came to reorganising stroke services in London.

Before 2010 services were provided in about 30 hospitals, but now emergency care is provided at eight specialist centres. The changes met with limited resistance.

Why? Speak to those involved with the shake-up, and they will tell you about the countless public events they held and the amount of literature they produced to inform people about the changes.

But they had one huge advantage. The changes were backed by money to invest in new equipment to support the specialist centres and allow the local hospitals losing their units to concentrate on providing rehabilitation care.

The latest review teams have not been so lucky. There was £1.8bn set aside for transformation projects this year, but it had to be used to pay off the deficits racked up by hospitals last year.

There is virtually nothing left in the pot to help make sure the changes work.