Why the NHS is performing miracles

- Published

- comments

It has been a remarkable few weeks for the health service hasn't it? The worst waiting times in A&E for over a decade. Patients left for hours on trolleys. Vital cancer operations being cancelled. Hospitals across the country declaring major alerts. A humanitarian crisis in the making, says the Red Cross.

But amid all this what we haven't heard is just how well the health service is coping. Given what it is facing, the NHS and, in particular, hospitals are performing miracles.

How? Let me explain. The NHS is in the middle of the most sustained squeeze on its funding in its history. Until 2010, the budget increased by an average of about 4% a year once inflation is taken into account to help it cope with rising pressures.

Since then, the average annual rise has been around 1% - and that will continue until 2020. The only period that comes close is the early 1950s when there was a cut in the NHS budget, prompting charging to be brought in for dentistry, prescriptions and spectacles.

And that was pretty quickly followed by large cash injections to get the NHS back on track.

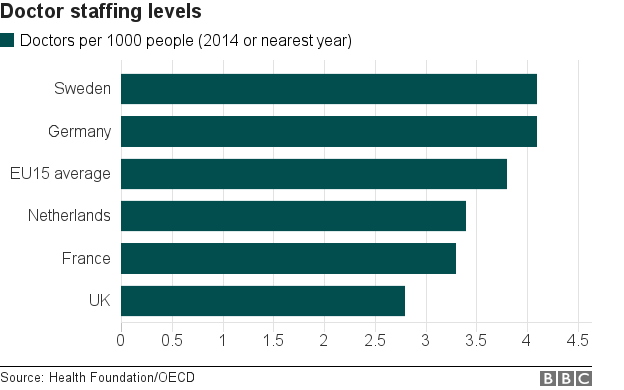

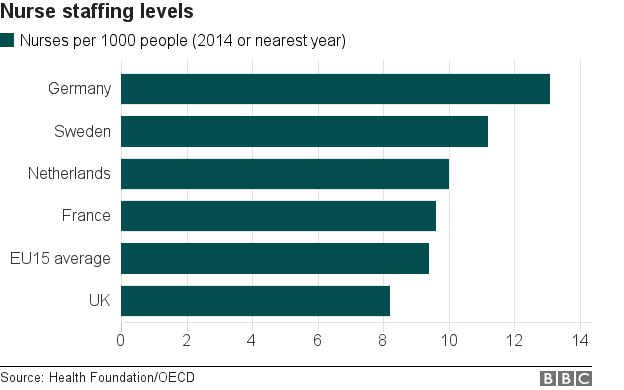

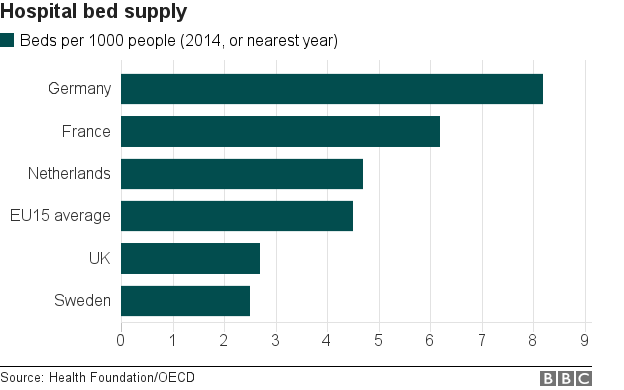

There's nothing like that this time. Instead, the health service is being asked to carry on as normal with fewer doctors, nurses and hospital beds than many other developed countries - as the graphs below illustrate.

Now international comparisons can be difficult. You could argue, for example, that Germany only has so many more beds because its counts long-stay beds reserved for elderly people in its health figures whereas in the NHS they come under the nursing home sector, which is separate.

Nonetheless they pose an interesting question: are we simply expecting too much of the NHS?

Anita Charlesworth, a health economist at the Health Foundation think tank and former Treasury official, thinks so. She says the NHS is being asked to provide "world class access" without the corresponding levels of funding and staff.

Looked at like that, it puts the recent performance in a slightly different light.

Faced with rising numbers coming in the front door (A&E) and increasing difficulty getting patients out the back (because of cuts to social care services), hospitals in England have found themselves full-to-bursting.

In recent weeks, bed occupancy rates have hit 95%. Now that may not sound like the definition of being full, but it is well above the 85% recommended threshold for a hospital to work effectively.

Above this level hospitals start to unravel, patients end up in the wrong places, infection rates start to rise and a backlog of patients builds up in corridors, in A&E and outside in ambulances dropping patients off.

Yes, some of this has started happening, but in many respects you would have expected performance to deteriorate even more than it has.

During the first week of the year - the most difficult so far this winter - more than three-quarters of patients arriving in A&E were still seen in four hours.

Yes the rate of-called "trolley waits" - where patients admitted as an emergency are left waiting more than four hours for a bed - doubled to one in five patients. But the number of "dire" 12-hour waits only amounted to 0.5%.

A week later bed occupancy rates had risen slightly - and guess what happened? Performance actually improved on many measures.

Ask anybody working in the health service and they will say this is down to the dedication and hard work of hospital staff.

Lord Kerslake, chairman of King's College Hospital in London and a former senior civil servant, has described the efforts of staff at his hospital as "extraordinary", while the BBC coverage over the past week or so has been full of doctors, nurses and managers recounting how everyone is pulling together.

But there is more to it than that. The NHS has become very adept at managing pressure points. Daily reports are sent from hospitals to NHS Improvement, a newly-created regulator, about everything from the number of ambulances queuing outside A&Es to how many patients are stuck on trolleys inside.

It means when there is a problem resources are immediately deployed by bosses at the centre.

Extra managers are deployed, GPs and council care staff geed up and beds at local nursing homes used to move patients out of hospital.

The result has been that the NHS has been able to - by and large - prevent the situation spiralling completely out of control and into a full-blown national crisis.

Those involved in the process speak in admiration of the way the regulator has managed the situation.

But make no mistake, this is fire-fighting and, as such, it can only last so long. An outbreak of flu or a sustained cold snap could alter the picture completely.

And if it does not happen this winter, what about next? Or the one after that?