Gene therapy: Deaf to hearing a whisper

- Published

Deaf mice have been able to hear a tiny whisper after being given a "landmark" gene therapy by US scientists.

They say restoring near-normal hearing in the animals paves the way for similar treatments for people "in the near future".

Studies, published in Nature Biotechnology, external, corrected errors that led to the sound-sensing hairs in the ear becoming defective.

The researchers used a synthetic virus to nip in and correct the defect.

"It's unprecedented, this is the first time we've seen this level of hearing restoration," said researcher Dr Jeffrey Holt, from Boston Children's Hospital.

Hair defect

About half of all forms of deafness are due to an error in the instructions for life - DNA.

In the experiments at Boston Children's Hospital, Massachusetts Eye and Ear and Harvard Medical School, the mice had a genetic disorder called Usher syndrome.

It means there are inaccurate instructions for building microscopic hairs inside the ear.

In healthy ears, sets of outer hair cells magnify sound waves and inner hair cells then convert sounds to electrical signals that go to the brain.

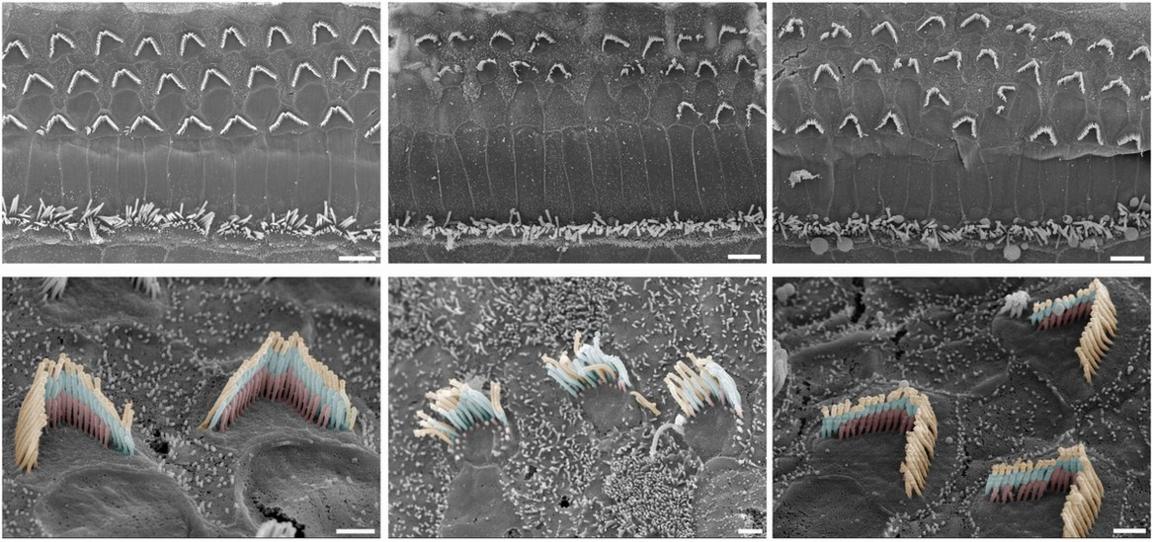

The hairs normally form these neat V-shaped rows.

Left: Normal ear hairs. Middle: Defective ear hairs. Right: Repaired ear hairs.

But in Usher syndrome they become disorganised - severely affecting hearing.

The researchers developed a synthetic virus that was able to "infect" the ear with the correct instructions for building hair cells.

Experiments showed that once profoundly deaf mice could hear sounds down to 25 decibels - about the volume of a whisper.

Dr Gwenaelle Geleoc told the BBC: "We were extremely surprised to see such a level of rescue, and we're really pleased with what we have achieved."

There are about 100 different types of genetic defect that can cause hearing loss. A different therapy would be needed for each one.

Dr Holt told the BBC News website: "We've really gotten a good understanding of the basic science, of the biology of the inner ear, and now we're at the point of being able to translate that knowledge and apply it to human patients in the very near future."

One of the big questions will be whether the synthetic virus is safe.

It was based on adeno-associated virus, which has already been used in other forms of gene therapy.

The researchers also want to prove the effect is long-lasting - they know it works for at least six months.

There are also questions about the "window of opportunity". While the therapy worked in mice treated at birth, it failed when given just 10 days later.

Dr Ralph Holme, the director of research at Action on Hearing Loss, said: "This research is very encouraging.

"However, there is a concern that delivering this gene therapy at birth to babies with Usher may be too late [as the ears are more developed in people than mice by birth].

"The technology may be better suited to treating more progressive forms of hearing loss."

Follow James on Twitter., external

- Published9 July 2015