Could ants tackle the 'antibiotic apocalypse'?

- Published

I was born in India and, as a young child, I developed a serious gut infection that would have killed me if it hadn't been for antibiotics.

These days a young child in India, with the same condition, would be far more vulnerable because of the huge and rapid rise in antibiotic resistance in that part of the world.

The problem is not, of course, confined to India. It's estimated that antibiotic-resistant infections currently kill at least 700,000 people a year.

This is projected to rise to 10 million by 2050. What is particularly worrying is that as well as the emergence of antibiotic resistance and the threat it poses - there have been no new classes of antibiotics released in the past 30 years.

I wanted to make a documentary that explores the reasons behind the rise of the superbugs and what progress is being made to find new ways to counter them.

The producer of the documentary, Peter Gauvain, was keen to expose me to some of the more unpleasant superbugs around and then see if we could treat them.

Since this was clearly unwise, we compromised by creating life-size models of my head and body out of a nutrient-rich jelly called agar.

We used my body doubles - whom we dubbed "Microbial Michael" - to experiment on.

The results were fascinating and rather disturbing.

We started by swabbing my real body and then wiping these microbes on to my body double.

The right hand side of Microbial Michael had previously been saturated with a powerful, broad spectrum antibiotic.

How long would the antibiotic hold the bacteria at bay? Answer: not long at all.

Within days both sides of "my" body had become a battlefield of competing microbes, some of them quite nasty pathogens.

Phages faith

So what about novel treatments?

The encouraging thing is that we did come across a number of different approaches to fighting the threat of antibiotic resistance that were promising.

One of the oldest approaches, which in the West is only now coming back into fashion, is the use of viruses to attack bacteria.

Just as we are prone to viral infections, such as the common cold, so are bacteria.

The viruses that infect and kill bacteria are known as bacteriophages or phages.

It's been estimated there are more than 10 million trillion trillion phages around, which is more than every other organism on Earth, combined.

Phages were first discovered more than a century ago and have been used to treat bacterial infections in a number of specialised centres in Central and Eastern Europe ever since.

There's a clinic in Poland where they use phage therapy on patients who have infections that are resistant to every known antibiotic.

There, we met a woman called Boguslawo, who had developed an infection in her leg after stepping on a rusty nail, which neither antibiotics nor conventional therapy could heal.

Faced with the choice of trying phages or having her leg amputated, she put her faith in the phages and, so far, that faith seems to be justified.

Packed with potential

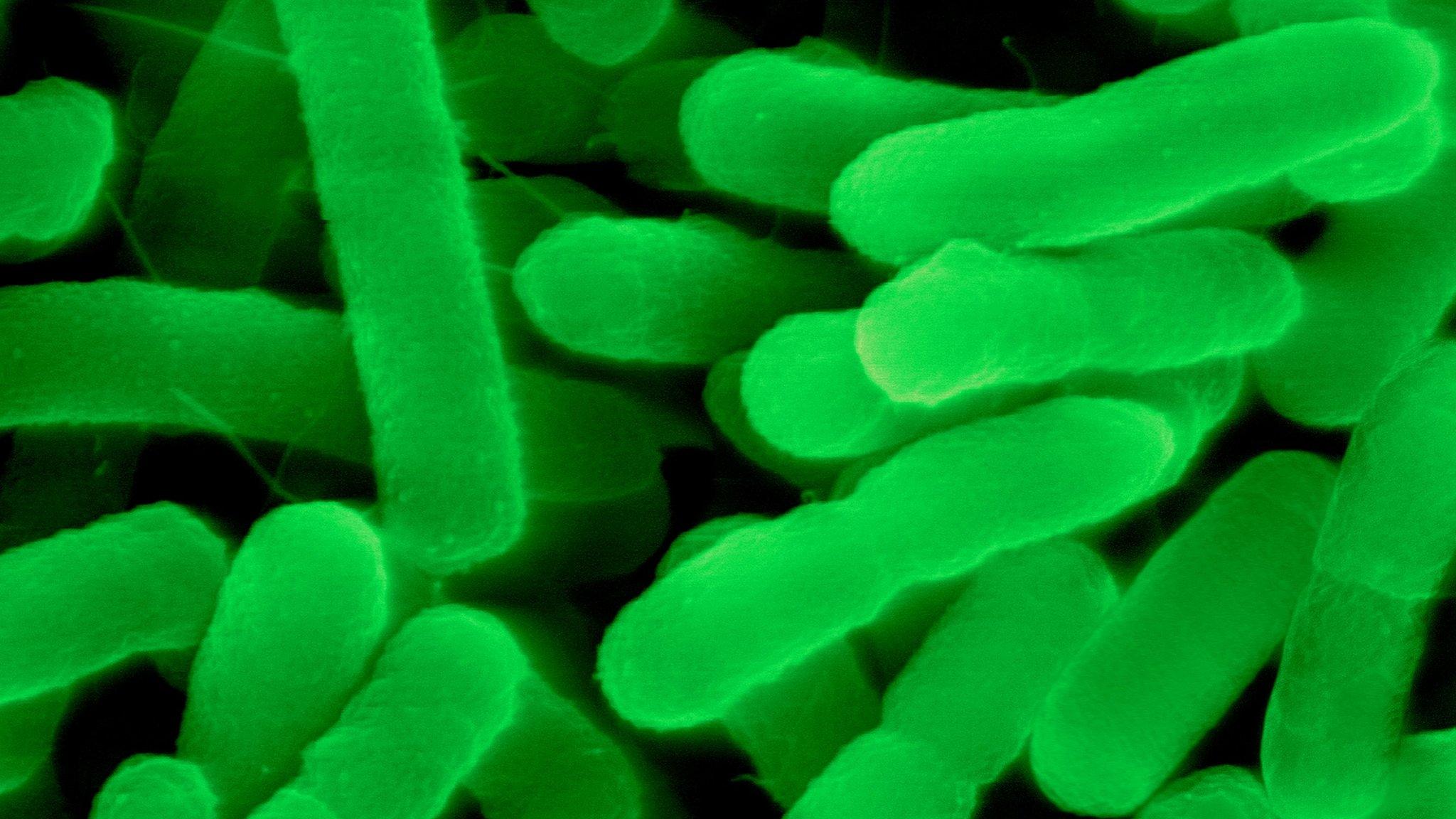

Dr Alex Betts, of Oxford University, is one of a handful of scientists in the UK currently working with phages, and he kindly agreed to demonstrate their effectiveness by infecting my agar double with a superbug called pseudomonas.

This causes septicaemia (an infection of the blood) and pneumonia, both of which can be fatal. In short, it's nasty.

He swabbed my agar face with a multi-drug resistant strain of pseudomonas and then covered part of it with a small bandage, impregnated with phages.

Some time later, when we examined my infected face under ultraviolet light, it was clear that the phages had done their work.

All the rest of the face had been colonised by pseudomonas, apart from the small patch where he had put the phage bandage.

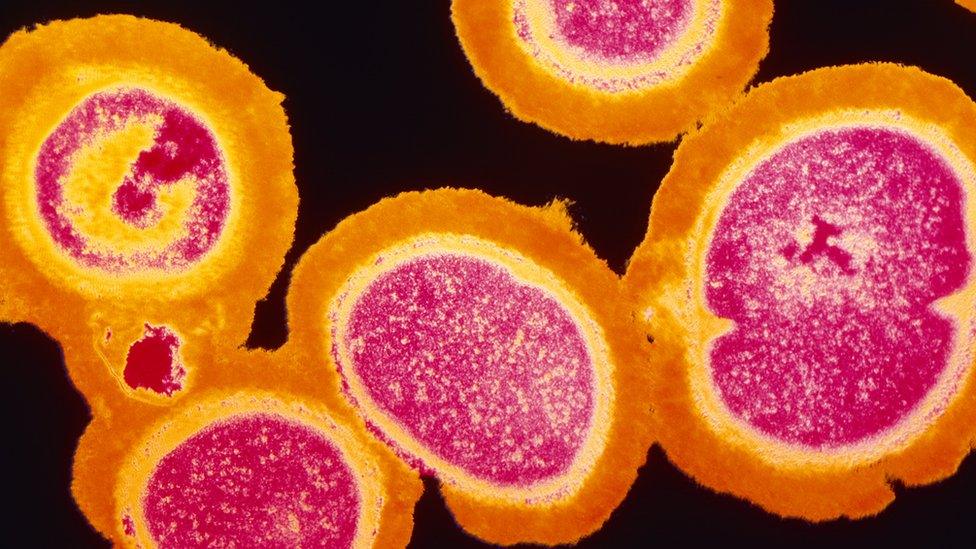

MRSA is one of the best known "superbugs"

There have been no proper clinical trials of phage therapy in the UK yet, so they won't be seen outside of the lab any time soon.

But I'm convinced that these viruses are packed with potential.

As Dr Betts explained, one of the great advantages of phage therapy is there is less risk of bacteria developing resistance.

"Phages need to infect bacteria in order to survive," he said.

"And if antibiotic resistance evolves, they can co-evolve rapidly.

"They're not going to replace antibiotics, but there are certain roles that they can fill that will ease the pressure on our existing therapeutics, buy us time to develop new antimicrobials.

"And phages can certainly be used alongside antibiotics."

As well as phages, we also tried infecting and then treating my body double with a novel antibiotic derived from ants, discovered by Prof Matt Hutchings and his team at the University of East Anglia.

This time we infected "my" face with the superbug MRSA (methycyliin resistant staph aureus), which - I'm pleased to say - the ant antibiotic was able to fight off.

Prof Hutchings is cautiously excited about their discovery, as he is well aware that developing new drugs is hugely expensive and can take a great deal of time.

And with a potential antibiotic apocalypse approaching fast, time is not on our side.

Michael Mosley vs The Superbugs is on BBC Four on Wednesday, 17 May, at 21:00 BST.

Join the conversation on our Facebok page, external.

- Published4 February 2017

- Published13 January 2017

- Published4 November 2016