How lack of sleep affects the brain

- Published

Scientists in Canada have launched what is set to become the world's largest study of the effects of lack of sleep on the brain.

A team, at Western University,, external Ontario, want people from all over the world to sign up online, external to do cognitive tests.

The specially devised computer games test skills such as reasoning, language comprehension and decision-making.

I joined a group of volunteers trying out the tests and had my brain scanned while doing them.

Trailblazing

Prof Adrian Owen, a British neuroscientist based at the Brain and Mind Institute, external in London, Ontario, is leading the study.

He told me: "We all know what it feels like to not get enough sleep but we know very little about the effects on the brain; we want to see how it affects cognition, memory and your ability to concentrate."

The team will collate the cognitive scores and see the variations depending on how much sleep people have had.

Everyone's sleep requirements are different, but if enough people join the study, it may allow scientists to determine the average number of hours needed for optimum brain function.

I joined four volunteers spending the night at Western University, where we road-tested the brain games and were able to demonstrate how lack of sleep affects cognitive performance.

The volunteers (clockwise from top left): Dr Hooman Ganjavi, Sylvie Salewski, Evan Agnew, Cecilia Kramar

The volunteers

Dr Hooman Ganjavi, aged 42. Psychiatrist who is regularly on-call overnight: "Four to five hours sleep a night is typical for me. I know that lack of sleep increases the risk of heart disease and stroke, but, like many doctors, I don't apply it to me."

Sylvie Salewski, aged 31. Mother of two girls under five: "A good night is when they wake me only two or three times; I can't remember what it is like to sleep through the night undisturbed, and I often feel fuzzy the next day."

Evan Agnew, aged 75. Retired night clerk. "I've never needed eight hours' sleep all at once, and at my age I don't think I need more than four hours in one go. I will top up my sleep during the day with a nap or two."

Cecilia Kramar, aged 31. Neuroscientist who does cognitive research with nocturnal mice, meaning late nights in the laboratory: "When I don't get much sleep, I cannot do anything complicated the next day, like reading a scientific paper, because my brain does not function well."

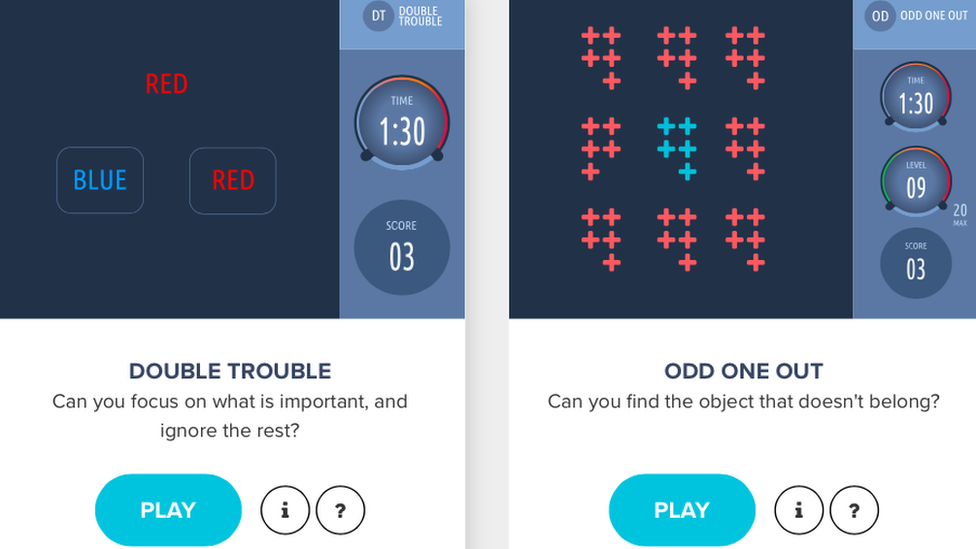

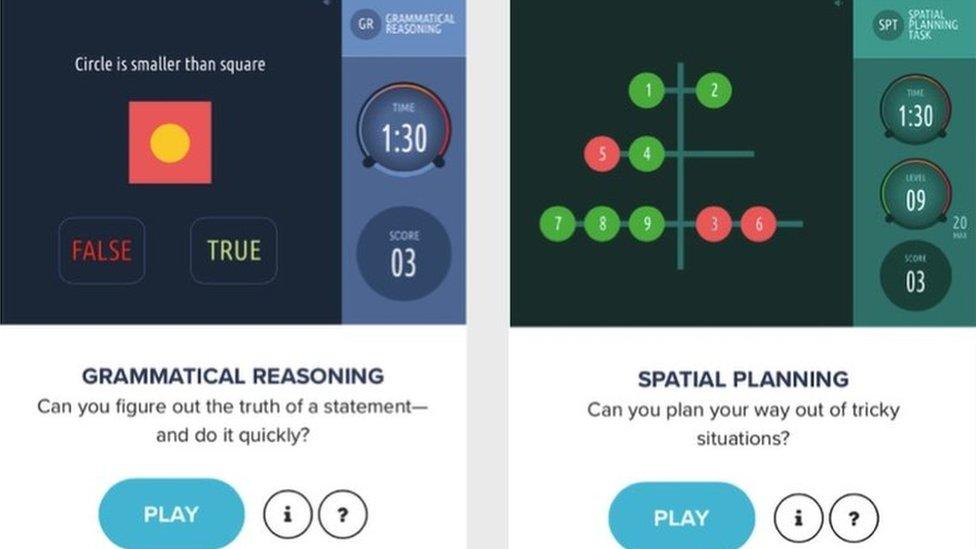

In Double Trouble, you must click on the word below that matches the colour of the word above. Odd One Out is as simple as it sounds, except that the game gets progressively harder

The tests

The tests can be played on any computer, tablet or smart phone.

Double Trouble: This looks simple but really stretches the grey matter. You have to click on the word below that corresponds to the colour in which the word above is written. So, if the word at the top is "blue", but is coloured in red, you must click on the word below that is coloured red, even if it is written as "blue". Fiendish.

Odd One Out: This starts simple but gets increasingly complex as you try to find the one shape that is different from the others.

Two more of the brain games - Grammatical Reasoning looks simple until the statements at the top are negatives. In Spatial Planning, you click on the numbers to move them into the right position

Grammatical reasoning: Is the statement about a diagram true or false? Sounds easy, until you begin dealing with negative statements.

Spatial planning: This tests the ability to plan ahead - like all the games, it measures cognitive skills we use repeatedly during the day.

How did we do?

After staying up until 04:00, we were allowed four hours' sleep.

When we re-did the cognitive tests later in the morning, Evan, Cecilia and I scored significantly worse than we had the night before.

Hooman - who is used to being on-call and responding to patients - did not see much of a dip in his score, while Sylvie's actually improved.

Sylvie said: "Although I feel a bit fuzzy this morning, maybe I've just got used to functioning on very little sleep; I have to be on as soon as my kids wake up, so it's normal for me."

I have long known that I don't function well when sleep deprived, so it was no surprise that my cognitive scores dipped dramatically in the morning.

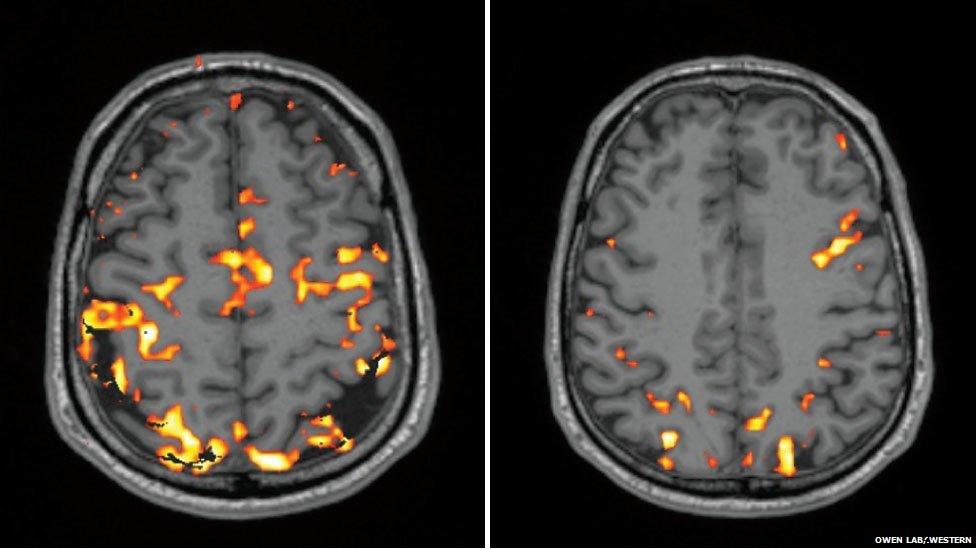

In order to find out what might be happening in my brain, I repeated the cognitive tests while inside an MRI machine.

I was scanned twice - after a normal night's sleep and then after the sleep-deprived night.

The functional MRI scanner is able to detect blood flow in the brain - so the areas that are working hardest show increased levels of activity, shown as orange coloured blobs.

The scan on the left shows my brain activity during cognitive tests after a normal night's sleep, compared with my sleep-deprived brain, on the right

The comparison between the scans was stark: after being sleep deprived, my brain was well under par - there was much less going on up there.

Prof Owen gave the scientific explanation: "There is much less activity in the frontal and parietal lobes - areas we know are crucial for decision making, problem solving and memory. "

We all know that it is dangerous to drive when tired, because our reaction times are impaired and we might fall asleep at the wheel.

But the more subtle effects of sleep deprivation on day-to-day living are far less understood.

Prof Adrian Owen, of the Brain and Mind Institute, Western, is leading the sleep cognition study

Prof Owen told me: "It may be that lack of sleep is having very profound effects on decision making and perhaps we should avoid making important decisions like buying a house or deciding whether to get married when we are sleep deprived."

Why it matters

We spend nearly a third of our lives asleep, and it is as vital to our wellbeing as the food we eat and the air we breathe.

But our 24-hour culture means we are getting less sleep than ever.

Last month, a paper in Nature Reviews Neuroscience, external said there was "remarkably little understanding" of the consequences on the brain of chronic sleep loss.

It spoke of the "precipitous decline in sleep duration throughout industrialised nations", adding that more research was urgently needed.

Those who volunteer for the sleep study, external may help find some of the answers needed by both science and society.

Fergus Walsh tried out the tests as he got more and more tired

Follow Fergus on Twitter, external

- Published12 May 2016

- Published15 May 2015