NHS pilot scheme taps into skills of refugee doctors

- Published

Refugee doctor Rouni Youssef with his mentor Dr Sue Jones and an elderly patient

A pioneering scheme that aims to harness the skills of refugees fleeing conflict and unrest in their home countries could help boost health services in north-east England.

Middlesbrough has the highest number of asylum seekers in the UK. Around one in every 186 people in the town is seeking refugee status, well over the government guidelines of no more than one in every 200 of the local population.

But many of the refugees are skilled professionals such as doctors or pharmacists, skills that happen to be in short supply in the area.

I have been to meet the foreign doctors who are participating in the scheme. Unable to practise their profession at home, they are embracing the opportunity to use their skills in an understaffed NHS.

Rouni Youssef, 27, picks up a patient's notes from the trolley outside the curtained cubicle and begins to thumb through the details.

"Interesting," he mutters to himself. "I think we should do an MRI."

I ask him what the day ahead on the hospital ward is looking like but Dr Youssef does not hear me. He is focused on the medical details before him, his eyes flicking feverishly over the scans like a sleuth over clues.

"Maybe some kidney malfunction here," he says.

Dr Rouni Youssef is currently on an unpaid clinical placement

Dr Youssef is polite and friendly towards me but I know I am holding him back from what he would rather be doing. It is, after all, what he has dreamed of doing all his life and what he has spent so many years training to do.

"I'm a Kurd from Aleppo," he shrugs. "And I'm a medical doctor but it just became too unsafe to stay in Syria and in 2014, I had to flee.

"I ended up here in Middlesbrough with nothing: no friends, no family and no career. I couldn't be a doctor any more. You can't imagine how that feels. It was like someone had cut off a body part.

"I was nothing and I had to start from scratch."

But thanks to the scheme run by the North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Trust and a refugee charity called Investing in People and Culture, Dr Youssef once again is sporting a stethoscope around his neck.

He is currently on an unpaid clinical placement at the University Hospital of North Tees but he has just taken the second part of his Plab exams (an assessment conducted by the General Medical Council which all overseas doctors from outside the EEA must pass before they can legally practise medicine in the UK). If he passes, he will start applying for jobs in September.

"I'd love to be a consultant paediatrician," he admits shyly. "Babies are such dear little creatures - they're like angels, you know?"

Dr Jane Metcalf says the pilot scheme is a "win-win situation"

Dr Jane Metcalf, deputy medical director at the hospital, pops down to the ward to find out how his latest exams have gone.

She describes the Resettlement Programme For Overseas Doctors as primarily a humanitarian project to get skilled healthcare professionals back into practice but she also admits that, since the North East has a shortage of qualified doctors, it is also in the trust's interests to use their refugee resources.

The current scheme comprises 11 doctors and one pharmacist, from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, Sudan, Pakistan and the Congo.

"It's a win-win situation," Dr Metcalf explains. "Although the training is rigorous, the cost is low... to help the doctors through their exams and English tuition it's about £5,000 per doctor and when you compare that to the £250,000 it takes to train someone in the UK through medicine, it's pretty cost-effective.

"If we can get doctors like Rouni back into practice within a year that would be a tremendous achievement."

The biggest hurdle for the doctors though is passing the extremely high level, but requisite, English exam.

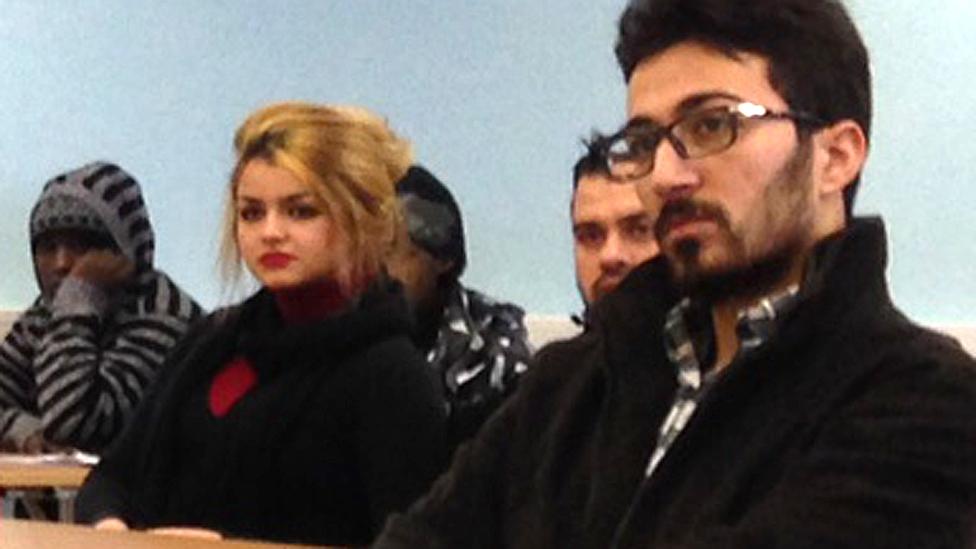

In an upstairs room at Middlesbrough library, the other doctors on the pilot scheme are learning about the inappropriate use of colloquial English in the written form.

Everyone is grumbling about the finicky example on the white board which, despite being a native speaker and having a university degree in English, even makes me pause for thought.

Eli (L) and Ahmad (R) are among those on the scheme studying for the extremely rigorous English exam

Eli, a GP from Congo, has had a long and difficult battle to win refugee status and was unable to join the scheme until his asylum papers were granted. While waiting however, he volunteered for the Alzheimer's Society and is now determined to work in geriatric medicine.

"We are refugees, yes," he smiles. "But we are doctors too. We don't take this opportunity for granted. Before this programme we had no road, no route. Now we have hope again. And we can give something back."

Ahmad, from Afghanistan, was just months away from completing his medical training as a specialist in paediatric orthopaedics when his life was threatened by the Taliban, forcing him and his family to flee Kabul.

"Now I'm optimistic for the future," he says. "I know that one day soon I will practise my passion again."

Outside the library I meet Bini Araia, founder of Investing in People and Culture, the charity working in partnership with North Tees and Hartlepool NHS Trust. He tells me that before the scheme's existence, many of the refugee surgeons and doctors, under pressure from their local job centre, were resigned to a life in the UK working in factories, garages or supermarkets.

"But we have a ready-made skill set!" he tells me. "And it's great to show with this programme that refugees can benefit UK society."

The programme shows refugees can benefit UK society, says IPC founder Bini Araia

Back on the ward at the hospital, there are no "baby angels" for Dr Youssef to treat today. Instead, his mentor, consultant physician Dr Sue Jones, asks him to join her as she examines an elderly patient who has been complaining of acute hip pain. Dr Youssef jogs eagerly to the patient's bedside.

"Well hello sir!" he beams. "And how are you feeling today? Is it really true you're 101?" He squats down and holds the man's hand, joking with him and reassuring him. I catch Dr Jones's eye. "Isn't he impressive?" she mouths delightedly.

Dr Metcalf wants to encourage other NHS trusts to implement the resettlement scheme for refugee doctors, something Dr Youssef welcomes.

"When I first walked back on to the ward," he remembers, "it felt like I had been fasting for 18 hours and then someone gave me a sip of cold, delicious water."

We walk together to the Rapid Assessment clinic.

"I want to be a doctor here in Middlesbrough," he continues, "because the people are so friendly." Then he grins."But the local accent here, it's a bit, um, fresh, isn't it?"

Emma Jane Kirby reports for BBC Radio 4's World at One programme.

- Published21 December 2016

- Published1 December 2016

- Published22 January 2016