Is there institutional racism in mental health care?

- Published

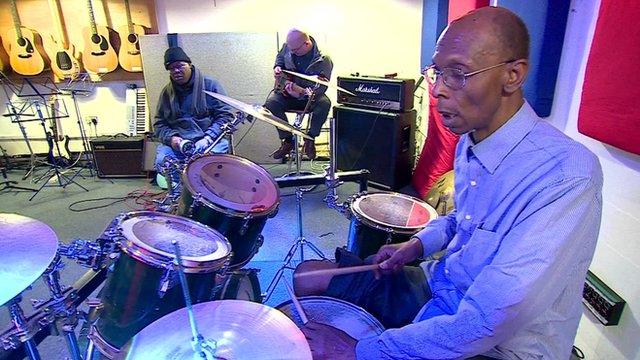

Eche explains how he was Tasered when sectioned under the Mental Health Act

Black people are being failed by the UK's mental health services because of "institutional racism", it has been warned. How does this affect those who experience it?

When Eche Egbuonu, who has bipolar disorder, was sectioned under the Mental Health Act, he should have been taken to a safe environment - usually a hospital - for a medical assessment.

Instead, he was taken straight to a police station.

"Being in the police cell was probably the worst thing they could have done to me in the state of mind that I was in," he tells the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme.

Under the Mental Health Act, a person can be detained if they are considered to be suffering from a mental disorder and in immediate need of care or control.

Eche was released two days later. But shortly after, following an altercation at his home, his parents called the police.

This time, after he refused to go willingly, one of the officers used a Taser.

Eche says: "I'm in my room, and I'm like, 'I'm not going [with police].' The first time, I was compliant.

"Physically they tried to get me down, that didn't work. So they brought the Taser out, 50,000 volts.

"Before I know it, I'm back in handcuffs.

"It's made me more resistant and distrusting of the system in general because it felt like a prison experience. I feel like a criminal."

'17 times more likely'

The matter of black overrepresentation within the mental health system is a complex one.

Statistics suggest a black man in the UK is 17 times more likely than a white man to be diagnosed with a serious mental health condition such as schizophrenia or bipolar.

Black people are also four times more likely to be sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

Issues such as unemployment and poverty play a part in the inequality, but there are fears that institutional racism also has a role.

Councillor Jacqui Dyer says mental health services must change for black communities to trust them

Jacqui Dyer - a councillor in Lambeth, London, the borough with the biggest black population in the country - believes this is the case.

She is vice-chair of the government-appointed Mental Health Taskforce for England.

"What we find is that there's a differential experience so these I might describe as structural inequalities, unconscious bias, institutional racism, whatever you're more comfortable with in terms of terminology which means decisions that are made in these structures, sort of biases those communities," she says.

Ms Dyer says there is a belief within some black communities that if you go into mental health services, "it's not that you get recovery, it's that you die [there]".

This, she says, leads to people "presenting later" for treatment, when their case is more severe.

"We have to change the narrative, by actually changing the services," she says.

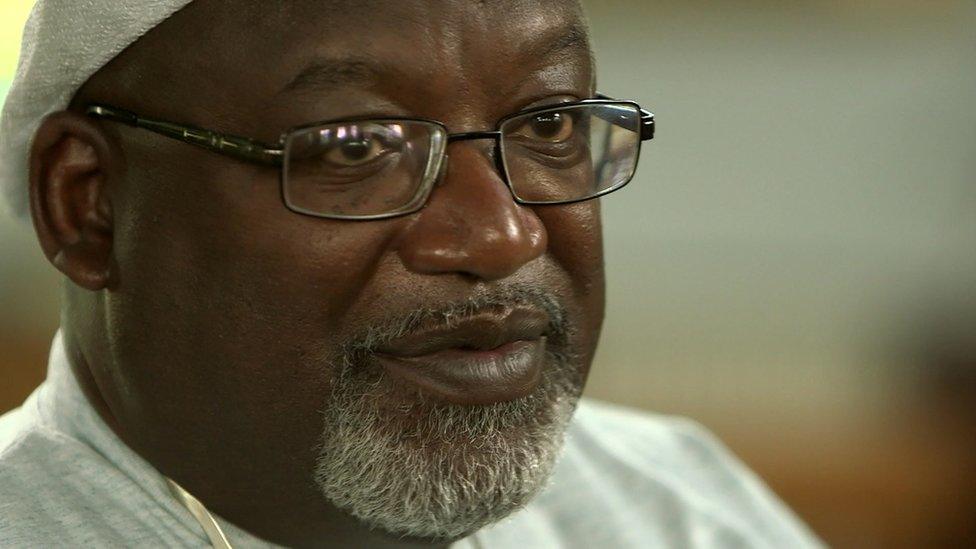

The Reverend Freddie Brown says the church is "indispensible to the solution"

According to the Reverend Freddie Brown, from Tooting New Testament Assembly, the Church could play a vital role in creating this change.

He is part of the Pastor's Network, set up because of concern about the number of parishioners presenting with mental health problems.

Church leaders in the network have taken accredited family therapy courses to try to improve the situation.

He believes - by working with other mental health services - they can be "indispensable to the solution".

'Feel suicidal'

Lorraine Khan, from the Centre for Mental Health, also believes "institutional racism" is embedded in the system.

A new report from the think tank found when black people tried to access help, they were less likely to receive the support they wanted.

They are now calling on the government to overhaul its approach to mental health to tackle the issue, which she says has been overlooked:

"I think there is a problem with institutional racism in the way we take action and try to improve things. This problem doesn't affect the majority of the country so it becomes a minority issue as far as commissioners are concerned.

"We find there's not the investment in research to improve the programmes that young men and women say they want. It's not considered the priority. The priority is, all the services are geared towards white people."

A Department of Health spokeswoman said: "We want to make sure that everyone, regardless of ethnicity, age or background, gets the mental health treatment they need.

"Work to consider reform of mental health legislation will begin to ensure mental health is prioritised in the NHS in England - and in part reflecting concern about the disproportionate rate of detention of black people under the existing system."

Maitreya, a singer-songwriter, was sectioned for a second time a few weeks ago, following an argument with a family member.

She says she found it difficult to access mental health care from the NHS in the year before she was detained.

"I was actually trying to tell them, 'I feel very much suicidal at the moment.'

Maitreya says she was not taken seriously when she reported suicidal thoughts to doctors

"I took myself into a hospital. I took myself into A&E. I've called ambulances."

But Maitreya says she was not taken seriously.

"It's made me lose trust in the mental health service.

"Now I've gone through a whole process of being sectioned - and I need more help to deal with the trauma - I'm scared because I'm like, 'How will the help come now?'"

After being sectioned, Maitreya has now been diagnosed with psychosis, something she disputes.

When she was detained she rejected medication, saying she had developed her own coping mechanisms.

According to some experts, black people are more likely to be medicated while admitted to mental health services.

Donald Masi, a psychiatric doctor, believes this is the result of a wider cultural perception that black people are more dangerous.

"Say there's a petite 50-year-old white lady with a mental illness and a 6ft [1.8m] black guy with the same illness," he says.

Donald Masi says there is a societal perception of "black people being the aggressor"

"Both may be calm but may have episodes of irritability, frustration or aggression because they're distressed from their mental illness.

"People are more likely to think that the black guy is going to do something and hurt them, because essentially there is a cultural idea of black people being the aggressor."

Dr Masi says, however, that the problem is more of a wider societal issue, rather than one specific to the health service - adding that the NHS was "a lot better than it used to be".

Eche believes in his case "there could have been a subconscious [racial] bias".

He says: "When I think about some of the other people that I saw in the ward, I'm like, 'What that person was doing was definitely more aggressive than me - but they stayed in that open ward, they didn't come into intensive care.'"

Eche says "it was basically all BME [black and minority ethnic]" in the intensive care unit.

And the "whole system needs an overhaul" to deal with the ingrained bias.

"How race impacts your experience in the mental health system, how painful it is, I think something needs to be done," he says.

Watch the Victoria Derbyshire programme on weekdays between 09:00 and 11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News channel.

- Published18 February 2016