The refugee doctors learning to speak Glaswegian

- Published

Refugee doctor: 'I hope to make the UK proud'

Doctors who have travelled to Scotland as refugees are being given the chance to start working for the NHS through a training scheme. The BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme has been to meet those involved.

"When people say, 'I had a couple of beers', they don't mean two," jokes instructor Dr Patrick Grant, a retired A&E doctor training refugees to work for NHS Scotland - including in how to overcome cultural barriers.

One of his students is Fatema, who previously worked as a surgeon in the Middle East until she was forced to flee.

Having treated anti-government protesters in her home country, she herself had become a government target.

"I wish one day this country will be proud of me," she says.

Fatema is one of 38 refugees and asylum seekers on the course - a £160,000 programme funded by the Scottish government.

Based in Glasgow, it provides the doctors with advanced English lessons, medical classes and placements with GPs or hospitals.

The aim is to give the refugee doctors - who commit to working for NHS Scotland - the skills to get their UK medical registration approved.

'Like being handcuffed'

Fatema says coming to the UK and not being able to work as a surgeon had felt like being "handcuffed".

"I'm a qualified medical doctor. It's hard to start again from zero," she explains.

Maggie Lennon, founder of the Bridges Programmes which runs the scheme, says it is important for the UK to utilise its high-skilled refugees.

Maggie Lennon says the refugee doctors' clinical skills are very similar to those of doctors trained in the UK

"I always say to people, 'I imagine taking out an appendix in Peshawar is not that different to taking out an appendix in Paisley'.

"I don't think there's actually any difference in the clinical skills, I think where there is a huge difference is attitudes to patients and how medicine is performed," she explains.

The scheme is designed to overcome such hurdles, including the case of one surgeon who, Ms Lennon says, was unaware he would have to speak to patients, having previously only encountered them in his home country after they had been put to sleep.

Find out more

Watch Catrin Nye's full film on refugee doctors on the Victoria Derbyshire programme's website.

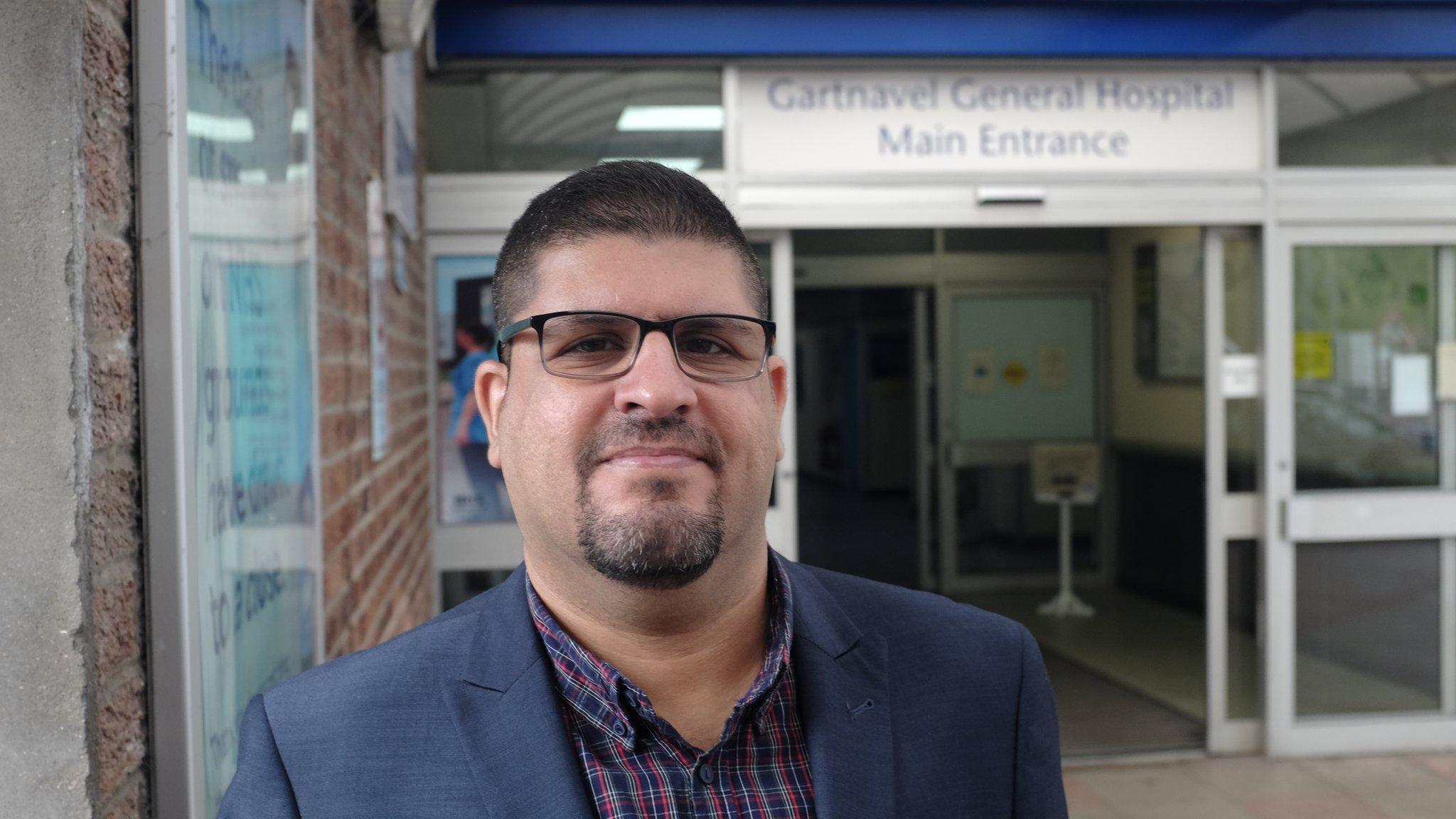

Laeth Al-Sadi, also on the course, used to be a doctor in the Iraqi army.

He came to Scotland to study but his life was threatened in Iraq and he was never able to go back.

One of the ways he has learned to work with patients in the UK is to use informal terms that might put them at ease - "How are the waterworks down there?" being one example.

Laeth Al-Sadi says being part of the scheme allows him to feel like he "belongs somewhere"

Language classes are an important part of the course, and placements with GPs and hospitals also allow the refugees to take note of local dialects.

Another doctor says he was confused by a patient who said they had a headache because of a "swally" - a term for an alcoholic drink.

Before refugees can even take their medical exams, they must pass tests to ensure they speak English at a high level.

They must pass a test called IELTS with a level of 7.5 - which even some doctors from the US and Australia have failed in the past.

Refugees take classes in "situational judgement"

All classes are taught in English. In one "situational judgement" lesson, the refugees are taught to assess what is wrong with a dummy patient based on its "symptoms".

Laeth says he feels lucky to be offered the possibility of a job in NHS Scotland.

"Lots of colleagues, or people who are doctors, are living here, and they are working other jobs.

"Some of them are even taxi drivers, which has [led to a loss of] hope for a lot of people."

Ms Lennon says this issue of under-employment among the refugee population "is as serious as unemployment".

"If someone's a qualified accountant and they're working pushing trolleys [in a supermarket], then there is an argument that they're taking a job from a poorly qualified person in this country," she adds.

Language classes are an important part of the scheme

Fatema says that despite having to leave the Middle East, she is glad she took the decision to treat anti-government protesters.

"My promise at medical graduation [was to] treat people equally, and try to do whatever is possible to help people. So I would do it again."

Dr Greg Jones, clinical lead at NHS Education Scotland, defended the use of government money on the scheme.

"As well as getting people back to their careers as doctors being the right thing to do from a humanitarian standpoint," he explains, "it's also the right thing to do financially.

"It would be a hugely wasted resource if people who'd already gone through medical training were not used as doctors."

Laeth says being part of the scheme allows him to feel like he "belongs somewhere".

"It means the world," he adds.

- Published3 August 2017

- Published18 July 2017