Care homes: Public 'pay unfair fees to plug £1bn shortfall'

- Published

Care homes have been applying unfair charges and over-the-top fees for self-funders, an official review shows.

The Competition and Market Authority found some homes had applied large upfront costs and charged families for weeks after their relatives had died.

The watchdog also highlighted how those paying for themselves were charged much more than council-funded residents.

The average weekly charge for self-funders was £846 - 40% more than local authority rates.

The CMA said it meant private individuals were effectively paying a multi-million pound subsidy every year to keep the ailing £16bn sector afloat.

It said another £1bn of government money was needed to create a fair and properly-funded system.

The year-long review by the markets watchdog also highlighted:

An inadequate complaints system making it difficult for families to raise concerns

Unclear terms and conditions

Fees being raised after residents have moved in

Insufficient support at a national level to help families navigate their way round the system

Families and friends being unfairly banned from visiting

You don't fight when you are bereaved

Jean Richardson's family were invoiced for four weeks room and care costs after her death

One family member who was left with charges is Debra Ives, from Thetford, Norfolk.

She said she and her siblings were "disgusted" when they were given a care home bill to cover the four weeks after the death of their mother, Jean Richardson, in October.

"The day after she died we removed her personal belongings, leaving the room free for future residents," she told the BBC.

"Within in a week we were issued with an invoice for four weeks post-death care costs of more than £3,000 to cover the use of the room, food and care she'd never get, and the cost of re-advertising the room.

"We were absolutely disgusted.

"We had signed a contract which stated that four weeks notice would be charged but we thought this would come into play if we had to move Mum. Never did we think it would mean a post death charge at full rates."

Liz Chesworth's family was charged more than £3,500 for a full month's care despite her father spending just 24 hours of the month in his care home before he died.

"After just being bereaved, I did not feel up to fighting over money," she said.

Meanwhile, Robert Hampson was horrified to discover he was being chased by a debt collection agency two years after the death of his aunt.

Her care home had tried to charge £5,000 for the cost of the place for the month after her death.

But he had refused, believing it "unreasonable".

Prof Martin Green, of Care England, defended some of the charges families face, saying financial liability did not end with death.

But he conceded there was a need for more "transparency" and said the CMA had raised some "useful" points.

The CMA is now taking action in test cases against a few homes responsible for the most extreme cases of upfront charges and fees being levied after death - some of which have been applied for four weeks.

Officials at the watchdog have issued enforcement notices and say they will pursue cases in court if the care homes fail to respond.

The CMA has also warned the rest of the sector to take note as the practices could be in breach of consumer protection law.

Is a shortage of government funding to blame?

More than 400,000 people aged over 65 live in care and nursing homes across the UK.

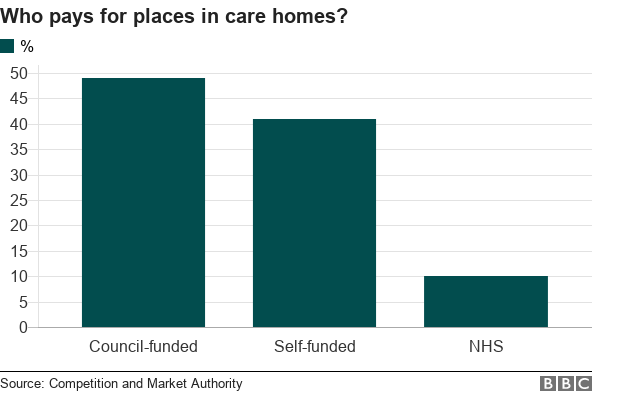

Four in 10 pay the full cost of the places themselves.

The rest receive some help with funding from councils - or in a minority of cases the NHS - as the system is means-tested.

Councils covering the cost of a care home place pay an average of £621 a week - more than £200 less than self-funders are charged.

The CMA said this was because councils had squeezed the rates they paid in response to a shortfall in their national funding and this needed to be looked at by the devolved governments.

"Without substantial reform, the UK won't be able to meet the growing needs of its ageing population," CMA chief executive Andrea Coscelli added.

Caroline Abrahams, of Age UK, said the CMA's "devastating report" showed the sector was "broken and living on borrowed time".

The business practices of some homes were clearly "unfair and exploitative", she added.

Councillor Izzi Seccombe, of the Local Government Association, said the "stark reality" was that councils simply did not have enough money to pay for places for those entitled to help.

She said it was "hugely disappointing" that more funding had not been found in the recent Budget.

But the Department of Health said there was already more money being pumped into the system in the short-term. Before the election an extra £2bn was set aside for the next three years.

"Next summer we will publish plans to reform social care to ensure it is sustainable for the future," a spokeswoman added.

- Published13 July 2016

- Published12 February 2016

- Published21 November 2015