NHS long-term plan: Are there enough staff to make it happen?

- Published

When Prime Minister Theresa May promised an extra £20bn for NHS England by 2023, she set a condition - the health service had to draw up a long-term plan setting out how it would spend it.

But unions say the plan, which includes aims to increase early cancer diagnosis, mental health support and care in the community - can work only if there are enough staff.

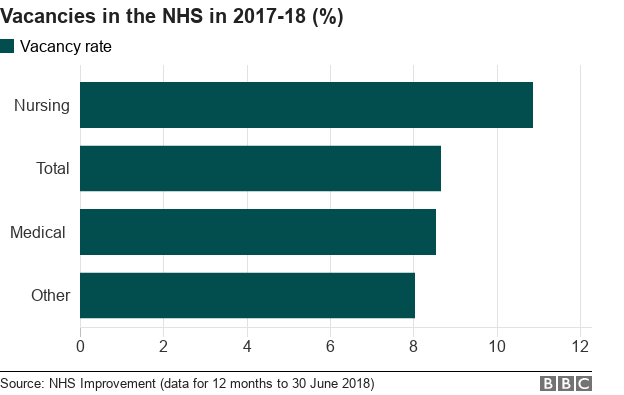

Over the past year, on average one in 11 NHS posts in England lay vacant, according to the body that oversees health trusts, NHS Improvement.

That adds up to more than 100,000 staff in a workforce of 1.2 million.

In nursing, the vacancy rate is even higher.

Will more staff be needed to deliver the plan?

Those are the vacancies now - but the long-term plan is about making the NHS better.

That includes:

more people having the tests required to diagnose cancer early

more people being cared for in the community, including mental health support, to stop them having to go to hospital

So how many more staff are needed to achieve the improvements set out in the plan?

Three independent health think tanks - the Nuffield Trust, King's Fund and the Health Foundation - have looked at how many extra staff they think will be needed, not just to fill current gaps and keep up with rising demand but also to make sure care is improving.

They estimate 250,000 additional staff will be needed by 2030, to keep up with demand and allow some extra for improvement. This will more or less cost the £20bn the government has promised.

This modelling, done before the publication of the plan, allowed some room for medical advances but didn't include some of the more specific pledges around DNA testing for children with cancer and mental health care - so figures could be higher.

For example, head of NHS England Simon Stevens told BBC Radio 4's Today programme that increasing cancer diagnostic testing would require about 1,500 more staff to be recruited.

Where are the existing gaps?

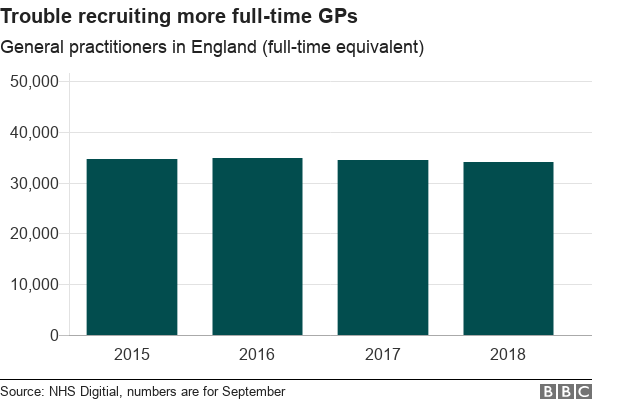

In 2015, the Department of Health (as it was then known) promised there would be 5,000 more GPs working in the NHS in England by 2020.

In September 2015, there were 34,592 full-time equivalent GPs working in the NHS in England. By September 2018, that figure had fallen to 34,205.

The actual number of GPs employed has gone up slightly, from 41,877 to 42,445, but because more are now working part-time, looking at the full-time equivalent, the staffing picture is worse than it was in September 2015.

Purely in headcount terms, another 4,366 GPs would need to be recruited in the next year to meet this target.

The long-term plan acknowledges that "while the number of new recruits has been increasing well, the number of early retirements and part-time working has more than offset this".

In nursing, where vacancy rates are highest, there were big cuts in staff numbers in the early years of the coalition government.

The overall number of nurses and health visitors working for the NHS in England fell by almost 8,500 between May 2010 and 2012 before going back up again by just over 11,500 by May 2018. It has crept up a little more since then.

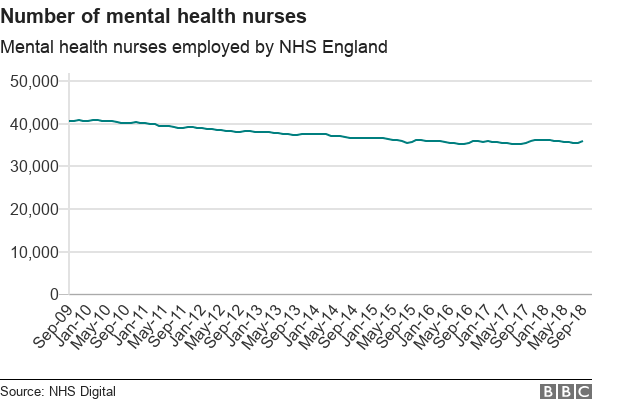

But once you break it down by different types of nurse, you get a slightly different picture.

For example in mental health - an area focused on in NHS England's plan - nurse numbers fell by 12% (while overall numbers went up). And in community nursing, there was a fall of 15% between May 2010 and 2018.

Staff costs

The NHS in England will receive the first chunk of the new money - an extra £6bn - from April this year.

Nuffield Trust policy analyst Sally Gainsbury said that this year, "the combined impact of staff pay rises, inflation and growing numbers of patients will mean it will face a cost pressure of £7.3bn".

"That would leave the NHS over £1bn short, despite the extra funding."

A representative from the think tank said this difference was likely to be made up in efficiency savings - but it wouldn't leave the health service with a lot of wiggle room.

And, according to the Nuffield Trust, an even greater concern than whether there is enough money available to pay for staff is ensuring enough staff are available - planning how many staff will be needed and making sure there are enough training places available, funding that training, and having an immigration system that enables staff to be recruited overseas where necessary.

The NHS England plan itself acknowledges that "over the past decade, workforce growth has not kept up with need".

It says "international recruitment will be significantly expanded over the next three years" as well as introducing incentives for "shortage specialties and hard-to-recruit to geographies".