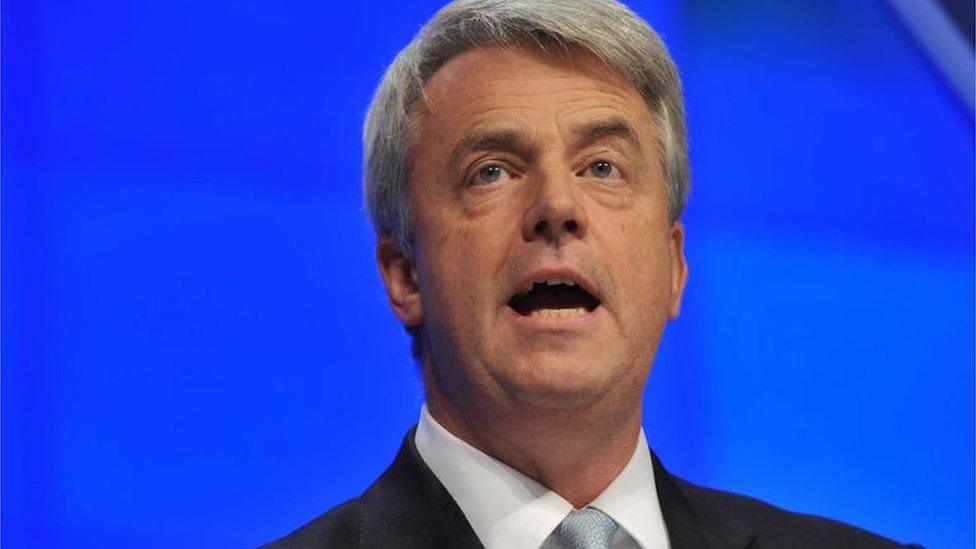

Are Andrew Lansley's NHS reforms being binned?

- Published

Consider this, it is just over three years since the last piece of the jigsaw in Andrew Lansley's controversial NHS reforms was put into place.

In 2015, health visitors moved into local government to complete the transfer of public health from the NHS to councils.

It completed what former NHS chief executive Sir David Nicholson once described as a reform programme so big it could be seen from space.

Now - with the country mired in Brexit - it is easy to forget just how tricky it got for the government in the early coalition years.

Unions and royal colleges lined up to oppose the changes and at one point it even threatened to turn the coalition partners against each other.

Eventually changes were made and Mr Lansley got them over the line with the Health and Social Care Act passed in 2012.

The restructuring created a new body, NHS England, to run the health service, set up new regulators and replace primary care trusts with GP-led clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) to organise local services, while handing healthy lifestyle programmes to town halls.

Underpinning the changes was the idea that greater competition in the NHS would help create a service fit for the 21st Century.

But on Monday that was effectively reversed, with the NHS Long Term Plan arguing collaboration was key.

It called for integrated care systems (ICSs) to be created across the country by 2021. These are partnerships that bring together hospitals, CCGs, community services, charities and councils, so they can work together rather than against each other.

A new way of working

Why is that important? The ageing population requires different services to work hand-in-hand, sharing expertise and staff to make sure people get the joined-up care they need.

If that sounds like NHS-speak, let's take a typical patient with whom the NHS deals. She is in her 70s, has heart disease, the early stages of dementia and lives alone.

She needs regular contact with her heart specialist, support from community nurses and, ideally, some company from befriending services which are run by the voluntary sector with support from councils.

If she needs to go into hospital - perhaps after a fall - in an ideal world she will be treated quickly and then the hospital staff will be in touch with community services to arrange the support to allow her to come home.

In a world where budgets are linked to individual services, where different organisations are encouraged to compete and tender for work, the pooling of resources and staff is not so easy.

But buried in among the 130 or so pages of the NHS Long Term Plan was a section recommending legislation could be important, arguing it could "accelerate" progress.

The government has not committed to that yet, but the fact it was included in the first place after close vetting of the report by ministers is telling.

What will happen next?

The interesting thing will be what happens now. NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens - the author of the plan - was pushed on this by the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee on Wednesday.

Understandably, he was reluctant to be pushed into making predictions.

But these integrated care systems are well on the way to being established. Within two or three years, there should be around 40 to 50 of them up-and-running.

Meanwhile, CCGs are merging. There were once 211 of them, but there are now 195 after a series of mergers.

But even that is misleading, with many sharing back-office functions and staff with others - many are their own organisations in name only.

In theory, they could easily start aligning themselves with the footprints of the ICSs and with some new legislation - CCGs have a range of statutory functions relating to accountability and budgets - there could be a whole new structure and way of working.

The same could happen at a national level with NHS England and NHS Improvement, which were both born from Mr Lansley's reforms. They already have a joint leadership team. Further merging is clearly possible.

Will it happen? It is too early to tell what the government is thinking and where it might go.

But Nigel Edwards, the influential chief executive of the Nuffield Trust think tank, believes a "significant unpicking" of Mr Lansley's reforms is on the cards and in time they will be judged as "one of the most major public policy failures" of all time.

If that is the case, it begs the question: why did the government go to all the trouble of pushing ahead with them in the first place?

- Published8 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017

- Published6 January 2017

- Published12 December 2016

- Published13 September 2016