Pharmacists warn of a 'surge' in shortage of common medicines

- Published

Pharmacists say they are struggling to obtain many common medicines including painkillers and anti-depressants.

This is leaving patients complaining of delays in getting hold of drugs and pharmacists paying over the odds for common medicines.

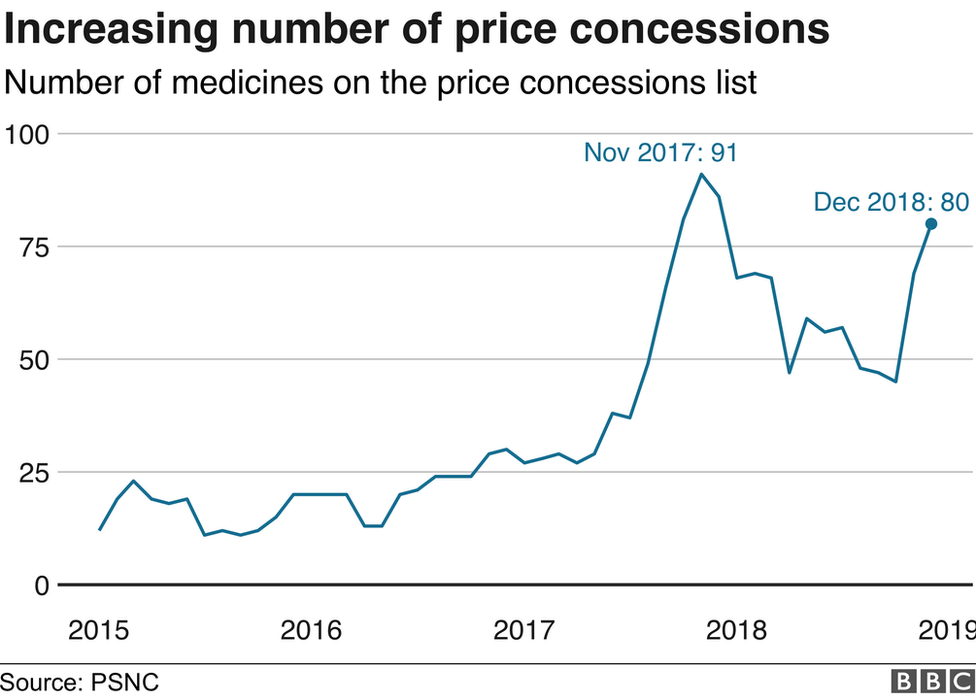

The BBC has found there has been a big rise in the number of drugs on the "shortage of supply" list for England.

There are 80 medicines, external in such short supply that the Department of Health has agreed to pay a premium for them.

This is up from 45 in October, although there was a spike in November 2017.

There are a number of reasons why this has happened, but there are now concerns that uncertainty over Brexit will only make the situation worse.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society said there was "a massive shortage and price spikes".

There is concern that this could affect some pharmacies' ability to deliver medicines, and cost the NHS more.

Pharmacies and patients in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland also appear to be experiencing similar shortages.

What does this mean for patients?

Most people should be able to get their prescriptions filled as normal.

But if they need one of the drugs that is running short, they might not be so lucky.

Melanie, who has fibromyalgia - a condition which causes pain all over the body - and hypermobility, wasn't able to get the anti-inflammatory naproxen from her pharmacist in December. Instead, she was given ibuprofen which didn't have the same effect.

"I was in floods of tears with the pain - it was awful," she told the Victoria Derbyshire programme.

"It makes a massive difference in my condition."

Without the drug, Melanie's inflammation increased to the point where she dislocated her thumb.

"It's difficult to explain how hard it is to deal with, suffering from chronic pain."

Melanie has experienced her drugs being out of stock before, but they usually reappear reasonably quickly.

This time, that hasn't happened.

Some pharmacists are sending patients back to their GPs to ask for a different medicine or dosage.

Others are giving as much of a drug as they can spare and sending people away with IOU notes for the remainder.

The best advice is to make sure you get prescriptions to your pharmacist in good time.

It is almost always possible to come up with an alternative.

However, that can be more difficult with conditions like epilepsy, where patients need to be on specific drugs.

What is the scale of the problem?

It is hard to obtain a definitive tally of which medicines are running short.

But the industry in England uses a list from the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC).

It shows which drugs are in such short supply and for which ones the NHS has agreed to temporarily pay a higher price.

The BBC has analysed this data and found that the number of medications on the list has grown six-fold in three years.

During this time period, the peak was in November 2017, but there has been a recent surge and figures for December show it is approaching that level again.

Academic researchers in Oxford University estimate that the cost of the 80 drugs in short supply would have trebled in December, external, from £11.4m to £37m.

This is the extra cost being paid by pharmacists, and then reimbursed by the NHS, for drugs in short supply.

What drugs are affected?

This is about prescriptions for generic medicines, rather than specific brand names.

For example, Nurofen is a common painkiller, but you can buy the same generic drug, ibuprofen.

Ash Soni, president of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, says he has never seen so many common drugs affected by shortages.

He explains: "The items are out of stock and unavailable. Patients are having to wait.

"We're having to send some patients back to the GP to get a different prescription, because we just can't fill them."

On December 2018's concession list, 28 drugs, or about a third, were among the 500 most commonly prescribed.

For example, furosemide is used to treat high blood pressure and other cardiovascular problems.

It comes in various dosages, but one type, 40mg tablets, is the 23rd most commonly prescribed drug in England.

Other drugs on the list include fluoxetine, which treats depression, and naproxen, which is an anti-inflammatory.

Mr Soni says naproxen went "completely out of stock" recently.

He did manage to track some down eventually, but it cost £6.49 a box - £2 more than the NHS last agreed to pay for it.

He says: "I've ordered 20 boxes today and that will last me about two or three days.

"We're dispensing at a loss. We're paying for patients to get their meds on the behalf of the NHS."

What do drug companies say?

Warwick Smith, director general of the British Generic Manufacturers Association, says stock levels can fluctuate.

He prefers to call it a "tightening of supply" rather than a shortage.

"It's normal for levels of availability to increase and decrease, which impacts prices," he adds.

The government stresses that two million prescription items are dispensed in England every day, and the vast majority of medicines are not in short supply.

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: "We continue to work closely with industry and partners to ensure patients receive the medicines they need and pharmacies are reimbursed fairly."

Why is this happening?

Industry figures all stress that there is no single, neat answer to explain such a complicated situation.

Suggestions for reasons behind the shortage include:

increased global demand

cost of raw materials

new regulatory requirements driving up costs

fluctuations in exchange rates

generic companies being unwilling to carry on selling unprofitable products.

Another possible explanation is that the NHS has done too good a job of driving down the prices it will pay for drugs.

The PSNC says this makes the UK a less attractive market for manufacturers.

Has Brexit had an impact?

The government has told manufacturers of both branded and generic drugs to stockpile six weeks' worth of supplies, so that people would still get their medications if we have a no-deal Brexit.

Hospitals, distributors and patients have been told not to stockpile their own supplies.

Medicine shortages were at their worst in 2017, and although recent figures show the issue could return to that level again, one expert says Brexit is "not a factor".

"Shortages have been a problem for some years. It's a fluctuating problem. They are now worse than ever," said former Liberal Democrat MP Sandra Gidley, a pharmacist and chairwoman of the English Pharmacy Board at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

Potential supply problems because of Brexit have led to manufactures being asked to keep a "buffer stock", Ms Gidley told BBC Radio 4's Today programme.

"Unfortunately what's been happening on social media over Christmas is that people have been… assuming this is because of Brexit. There are global issues at play here."

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: "We have not seen any evidence of current medicine supply issues linked to EU exit preparations."

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society in Scotland said the issue was a permanent feature of pharmacy life and can happen for a variety of reasons.

But Gareth Jones, of the National Pharmacy Association, thought while patients were not panicking, "unconscious stockpiling" along the supply chain appeared to be a "significant factor".

Martin Sawer, of the Healthcare Distribution Association, which circulates 92% of medicines in the UK, said some businesses could be "speculating on Brexit" - investing in stock in order to make money from it later.

"That's the nature of the market," he said.

Data analysis by Clara Guibourg and Wesley Stephenson

- Published18 December 2018

- Published23 October 2018

- Published29 November 2018